Why We're Bad at Predicting What Makes Us Happy

TL;DR: Your brain automatically notices race not because it cares about skin color, but because of an ancient coalition detection system searching for allies and adversaries. Landmark research shows that arbitrary visual cues like shirt color can override racial categorization, revealing that the key to reducing bias lies in creating meaningful cross-racial coalitions.

Your brain notices race in milliseconds, faster than you can think. Yet it completely ignores whether someone's wearing a red shirt or a blue one. This seems bizarre at first because both are visual features, both are obvious, both sit right there on the surface. But here's the twist that changes everything: race isn't what your brain actually cares about. What it's detecting is something far older and more fundamental to human survival.

Deep in the circuits of human cognition lies a mechanism that evolution sculpted over millions of years: coalition detection. Long before cities, writing, or agriculture, our ancestors lived in small bands of 20 to 150 people scattered across vast landscapes. In those environments, knowing who was on your team wasn't just useful - it determined whether you ate, whether you found a mate, whether you survived the next conflict with a neighboring group.

Coalition detection emerged as an evolved cognitive module, a specialized piece of mental machinery dedicated to one task: rapidly identifying allies and adversaries. This wasn't about logic or careful consideration. When another group appeared on the horizon, you had seconds to decide: friend or threat? The individuals who hesitated, who needed more information, who wanted to think it over - their genes didn't make it into the modern human genome.

Your brain's coalition detection system evolved over millions of years to answer one critical question: "Who's on my team?" In modern society, it uses race as a shortcut when the real signals aren't available.

But here's what makes this fascinating: those ancient hunter-gatherer bands didn't differ by race. Archaeological and genetic evidence shows that racial differences as we know them today emerged relatively recently in human evolution, long after coalition detection was already hardwired into our brains. Groups identified each other through kinship, shared language, territorial markers, and cultural practices - not skin color.

So why does race feel so automatic now? Because your coalition detection system is desperately searching for cues to answer its ancient question: "Who's on my team?" In the absence of the markers it evolved to use, it latches onto whatever visual differences it can find. Race became a proxy, a shortcut, a best-guess heuristic when the real signals aren't available.

In 2001, evolutionary psychologists John Tooby, Leda Cosmides, and Robert Kurzban ran an experiment that would fundamentally reshape our understanding of racial bias. They showed participants a series of photographs of men - some white, some Black - engaged in a heated argument. Half wore yellow shirts, half wore gray shirts. The shirt colors were assigned to cut across racial lines: some white men wore yellow, some wore gray, and the same for Black men.

Participants watched these images while hearing scripted arguments, then later tried to recall who said what. This "who-said-what" paradigm is a standard tool in memory research, and it reveals something crucial: the errors people make show you what categories their brains are using automatically.

Under normal circumstances, people make lots of race-based errors. They mix up two Black speakers or two white speakers, but rarely confuse a Black speaker with a white one. Race operates as a default organizing category, even when it's irrelevant to the task. This pattern is so robust it's been replicated dozens of times.

But when shirt color indicated coalition membership - when the argument was explicitly framed as yellow team versus gray team - something remarkable happened. Race-based errors dropped by about 50%. Participants suddenly started mixing up people by shirt color instead. A white man in yellow got confused with a Black man in yellow. The arbitrary, meaningless visual cue of shirt color had overridden race as the brain's primary sorting mechanism.

This became known as the "erasing race" effect. The name is a bit misleading - race doesn't actually get erased. Instead, coalition cues can be reassigned. When the brain receives clear, consistent signals about group membership from another source, it updates its categorization accordingly. The coalition detection system doesn't care about race per se. It cares about alliances. It just uses race when nothing better is available.

A 2020 meta-analysis examined nine independent studies testing the erasing race effect in the United States. The combined data showed a statistically significant impact, though the effect size was modest: about 0.14 on a correlation scale. That might sound small, but in the realm of unconscious bias research, it's notable for two reasons.

First, the effect was completely consistent. No matter whether researchers used students or community members, whether the study was published or unpublished, whether participants were male or female, the pattern held. There was no decline over time - studies conducted in 2014 showed the same effect as the original 2001 experiment - and no evidence of publication bias. In a field where replication failures are common, this kind of consistency is rare and meaningful.

"The erasing race effect is the reduction of the salience of race as an alliance cue when recalling coalition membership, once more accurate information about coalition structure is presented."

- Meta-analysis authors, Frontiers in Psychology

Second, the effect emerged from a single, brief exposure to coalition cues. Participants watched a short video or viewed some images, with minimal manipulation, and their automatic categorization patterns shifted. They weren't given extensive training, they weren't offered monetary incentives, they weren't explicitly told to ignore race. The coalition cues simply worked on their own, hijacking the categorization system at a level below conscious awareness.

Imagine scaling that up. What could happen in a workplace where teams collaborate across racial lines for months or years? In schools where students work together on projects that matter? In neighborhoods where people of different backgrounds unite around common causes? If even minimal coalition cues can measurably reduce racial categorization, persistent and meaningful coalition experiences could potentially have transformative effects.

Where exactly does coalition detection happen in the brain? Modern neuroimaging has given us some answers, and they're surprising. The fusiform face area, or FFA, sits on the underside of your temporal lobe and lights up every time you look at a face. It was discovered in the 1990s and initially thought to be a face-specific module, a piece of neural hardware dedicated solely to facial recognition.

But subsequent research complicated that picture. The FFA also activates when car experts look at cars, when bird enthusiasts identify bird species, when chess masters analyze board positions. It turns out the FFA isn't just about faces - it's about rapid, expert-level categorization of anything you've learned to distinguish automatically.

When people view faces of their own race versus faces of other races, the FFA shows differential activation patterns. This isn't necessarily conscious prejudice; it's the neural signature of in-group versus out-group processing. The brain dedicates more resources, more nuanced analysis, to faces it categorizes as belonging to the in-group.

More unsettling: studies using electroencephalography show that when people watch someone of another race perform a simple action like picking up a glass, their motor cortex fires less strongly than when watching someone of their own race. The motor cortex is part of the mirror neuron system, which underlies empathy and our ability to simulate others' experiences. Reduced activation suggests a subtle dampening of empathetic resonance toward out-group members, a neural signature of the boundaries coalition detection draws.

Yet even this isn't fixed. When researchers manipulated coalition cues in these experiments, the neural patterns shifted. Present strong enough signals about shared group membership, and the FFA starts treating other-race faces more like same-race faces. The hardware is adaptive, responsive to social context.

When does coalition detection start? Earlier than you might think, but not in the way you'd expect. Infants as young as three months show preferences for faces of their own race - but this preference is driven entirely by exposure. Babies raised in predominantly white environments prefer white faces; babies raised in more diverse settings show no such bias. At this stage, it's not about coalitions. It's about familiarity, about learning what "normal" faces look like based on who's around.

Around ages three to four, something shifts. This is when children begin demonstrating the cross-race effect: better recognition and memory for faces of their own racial group. It's also when they start articulating explicit racial categories and showing in-group preferences. The coalition detection system is coming online, starting to do its evolved job of sorting the social world into us versus them.

Children raised in diverse environments with cross-race friendships show significantly reduced racial bias compared to kids raised in racially homogeneous settings. The coalition detection system learns from experience.

But here's the crucial point: even at this early stage, the system is flexible. Children raised in diverse environments, children with cross-race friendships, children who receive even modest amounts of cross-race exposure - all show reduced racial bias compared to kids raised in racially homogeneous settings. The coalition detection system is learning what counts as in-group and out-group, and it's learning from experience.

This developmental window represents both a vulnerability and an opportunity. The flexibility that allows coalition detection to latch onto race in segregated environments is the same flexibility that allows it to transcend race in integrated ones. The mechanism itself is neutral. What matters is the structure of the social world it's learning to navigate.

Understanding coalition detection theory doesn't just satisfy scientific curiosity. It reframes some of society's most persistent challenges. Consider three domains where this research has direct implications.

Political polarization: American politics increasingly functions along tribal lines, where party affiliation triggers the same coalition detection mechanisms that race does. People remember arguments more accurately when attributed to someone from their political party, overestimate agreement with in-party members, and automatically distrust out-party sources. The sorting isn't based on actual policy positions - many Republicans and Democrats hold more nuanced views than party stereotypes suggest - but on coalition markers. Red state versus blue state, Fox News versus MSNBC, MAGA hat versus Black Lives Matter sign. These are the modern equivalents of yellow shirts versus gray shirts.

Workplace diversity: Corporations spend billions on diversity training, much of it ineffective or even counterproductive. Coalition detection theory suggests why. Training that emphasizes racial differences, that calls attention to who's Black and who's white, may actually reinforce the categorization it aims to disrupt. But initiatives that create cross-racial coalitions around shared goals - diverse project teams, mentorship programs that cross demographic lines, employee resource groups focused on substantive issues rather than just demographic identity - these align with how the coalition detection system actually works.

Education and criminal justice: The cross-race effect has documented consequences for eyewitness testimony and facial recognition accuracy. People are significantly worse at distinguishing and remembering faces of other races, a well-replicated finding with serious implications for criminal identification. Teachers show better memory for names and faces of same-race students. These aren't failures of moral character. They're predictable consequences of how coalition detection shapes attention and memory.

If coalition detection explains why race feels so automatic, can we use that same mechanism to make race less salient? The evidence suggests yes, but with important caveats.

The most straightforward approach is contact under conditions that create genuine coalitions. Not just diversity for its own sake, but structured situations where people of different backgrounds work together toward common goals, where success requires cooperation, where individual contributions are visible and valued. This isn't a new idea - social psychologists have studied the "contact hypothesis" for decades - but coalition detection theory explains why contact works when it does. It's not just about getting to know people. It's about rewiring the automatic categorization system to prioritize new coalitions.

Sports teams provide a natural laboratory. Teammates develop strong bonds across racial lines because the coalition signals are unambiguous: we wear the same uniform, we work toward the same victory, we rise or fall together. Research on multiracial sports teams shows reduced racial bias among players, effects that persist beyond the field. The key is that coalition membership is functional, not symbolic. It matters. It determines real outcomes.

"Movement was never just a means of finding food, but of finding one another across entire continents."

- Aeon Essays on hunter-gatherer societies

Military units show similar patterns. When soldiers depend on each other for survival, when trust across demographic lines becomes literally life-or-death, coalition bonds can override racial categorization powerfully. This doesn't mean the military has solved racism, but it does suggest that when coalition signals are strong enough and meaningful enough, they can substantially reshape automatic cognition.

The challenge is creating those conditions outside contexts of shared struggle. How do you generate coalition signals in a suburban neighborhood, a corporate office, a democratic society? How do you make team membership feel real and consequent when the stakes are abstract?

Coalition detection theory doesn't explain everything about racial bias. It doesn't account for systemic racism, structural inequality, the historical legacy of slavery and discrimination, or the ways power and resources get distributed along racial lines. Those are real phenomena with real causes that extend well beyond individual cognition.

What coalition detection theory does explain is the automatic, often unconscious tendency to categorize by race, to notice racial boundaries, to remember and trust in-group members more readily than out-group members. It explains why these tendencies are universal across cultures, appear early in development, and persist even among people who consciously reject racist beliefs.

And crucially, it offers a pathway to change that aligns with how our minds actually work rather than fighting against our evolved psychology. You can't simply decide to stop noticing race. The categorization happens too fast, too automatically, too far below conscious control. But you can give the coalition detection system new information. You can create contexts where racial boundaries become less relevant than other group memberships. You can build coalitions that cut across demographic lines.

This isn't a magic solution. It requires sustained effort, institutional commitment, and social structures that support cross-group cooperation. The yellow shirts versus gray shirts experiment shows what's possible, but it also shows the fragility of the effect. Take away the coalition cues, and people default back to racial categorization. The system is responsive to context, which means context matters. A lot.

Imagine a society deliberately structured to create meaningful coalitions across racial lines. Not through forced diversity quotas or mandatory sensitivity training, but through institutions and incentives that make cross-racial cooperation genuinely beneficial. Where neighborhoods are organized around shared interests rather than property values. Where schools group students by project teams and passion rather than tracking and ability. Where workplaces reward collaborative achievement more than individual competition.

This isn't utopian fantasy. Elements of it exist in hunter-gatherer societies that maintained extensive social networks spanning hundreds of kilometers, in multiethnic sports leagues, in disaster response teams, in collaborative online communities where race is invisible but shared purpose is vivid.

The irony is that coalition detection, the very mechanism that makes race salient in segregated societies, could be the key to making race less salient in integrated ones. Your brain sees race because it's searching for coalitions. Give it better signals, clearer markers of who's on your team, and it will happily use those instead.

The yellow shirts and gray shirts are all around us. We just need to make them visible.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

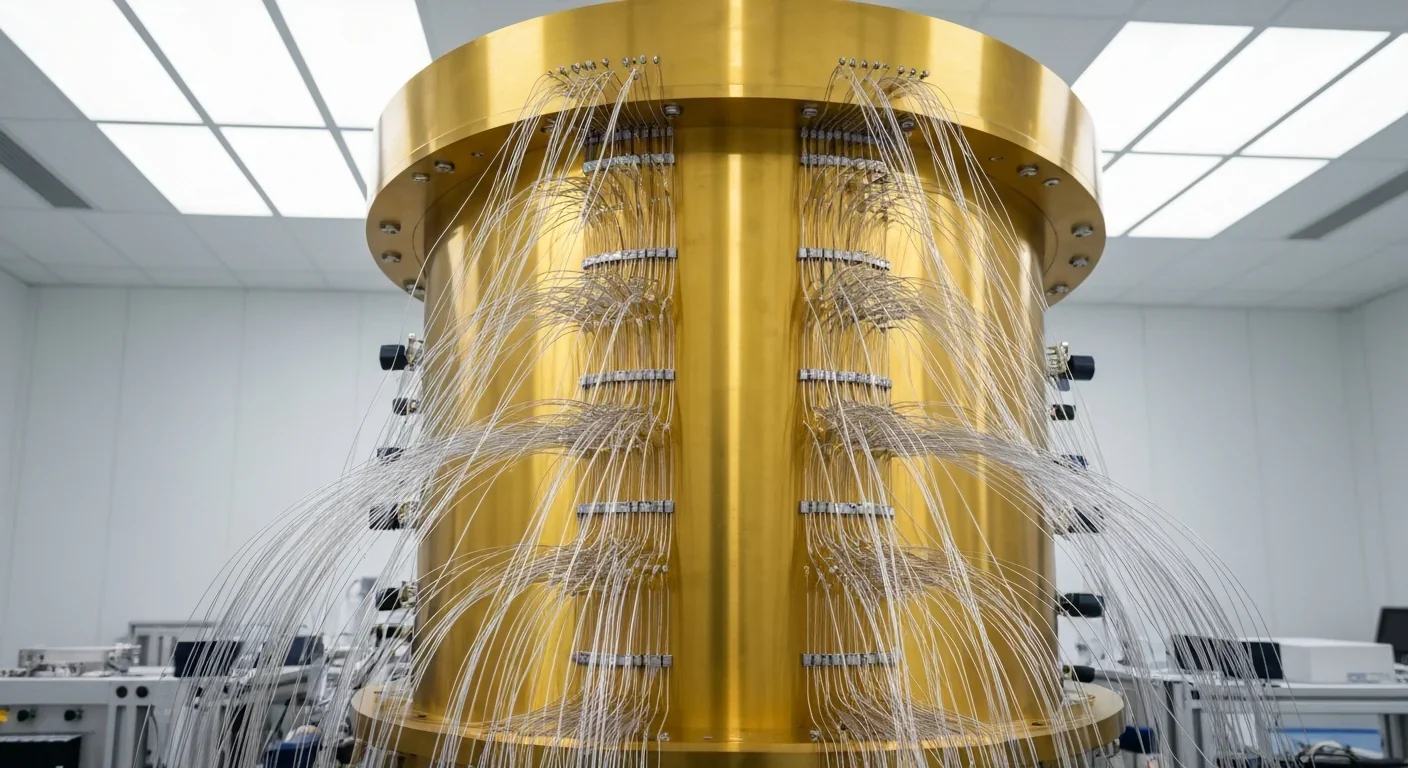

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.