Why Your Brain Sees Race But Ignores Shirt Color

TL;DR: Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Picture this: you've convinced yourself that moving to California will transform your life, that a new job will solve all your problems, or that winning the lottery would guarantee permanent bliss. But here's the uncomfortable truth - you're almost certainly wrong. This isn't a personal failing. It's a systematic flaw in how every human brain processes information about the future, and it's costing us money, time, and happiness in ways we rarely recognize.

The focusing illusion represents one of psychology's most powerful yet underappreciated phenomena. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman spent decades studying this cognitive bias, eventually distilling it into a deceptively simple principle: "Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you're thinking about it." When we contemplate any single factor - whether it's wealth, location, career status, or relationships - our minds magnify its importance while systematically ignoring everything else that contributes to our wellbeing.

This isn't just academic theory. Research on affective forecasting demonstrates that people routinely overestimate both the intensity and duration of their emotional reactions to future events. We imagine promotions will bring lasting joy, breakups will devastate us indefinitely, and major purchases will fundamentally change our satisfaction levels. The data tells a different story: most significant life changes produce emotional effects that fade within three to six months as we adapt to our new circumstances.

Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you're thinking about it - including your predictions about what will make you happy.

The mechanism behind this distortion involves what psychologists call focalism or anchoring bias - our tendency to fixate on salient information while neglecting the broader context. When you're house hunting, the gleaming kitchen dominates your attention. You're not simultaneously considering your commute, your neighbors, the local schools, your social life, or the thousand other factors that will actually determine your day-to-day experience. Your brain can't hold all those variables at once, so it simplifies by focusing on what's immediately visible.

The focusing illusion doesn't discriminate based on intelligence or education. In fact, experts often fall victim to this bias when making predictions in their own domains. Studies on impact bias reveal that even trained psychologists overestimate how positive outcomes will affect people's happiness levels. When we zoom in on any single variable, we inadvertently inflate its significance.

Consider the classic lottery winner paradox. Common wisdom suggests winning millions would guarantee happiness, yet research tracking actual lottery winners reveals a more nuanced reality. While winners do experience happiness boosts - contrary to the myth that they return completely to baseline - the effect isn't nearly as dramatic as most people predict. The hedonic treadmill ensures that we adapt to new circumstances, whether positive or negative, much faster than we anticipate.

A recent Irish study found that EuroMillions winners reported sustained improvements in financial security and reduced stress, but their baseline happiness levels shifted less dramatically than predicted. The money solved financial problems but didn't magically eliminate all sources of unhappiness - relationship issues, health concerns, and existential questions remained unaffected.

This pattern repeats across countless domains. Career changes, relocations, relationship transitions, and major purchases all follow similar trajectories: we overpredict their impact, experience a brief spike or dip in emotion, then gradually return toward our previous emotional baseline through a process called hedonic adaptation. The peak-end rule further complicates our ability to learn from these experiences - we judge past events primarily by their most intense moments and their conclusions, not by the average experience throughout, making it difficult to calibrate future predictions accurately.

The advertising industry has built a multi-trillion-dollar empire on exploiting the focusing illusion. Every commercial follows the same blueprint: isolate a single product feature, amplify its importance, and encourage you to imagine how different your life would be with this item. Predatory marketing tactics take this principle further by leveraging data analytics to identify and target specific vulnerabilities, essentially engineering an artificial focusing illusion around products or services.

"Predatory advertising can be largely understood as the practice of manipulating vulnerable persons into unfavorable market transactions through the undisclosed exploitation of these vulnerabilities."

- Wikipedia, Predatory Advertising

Modern advertising doesn't just highlight product features - it strategically manipulates attention. When a car commercial shows a vehicle driving through stunning landscapes, it directs your focus toward the experience of driving while you ignore maintenance costs, depreciation, insurance premiums, and the reality that you'll spend 95% of your time in traffic or parked in a garage. The illusion of marketing control extends to businesses themselves, where marketing teams often overfocus on current tactics while missing emerging opportunities.

One revealing case study involved a B2C client who saw conversions vanish because they'd become fixated on existing marketing channels while competitors exploited influencer platforms. After finally diversifying their approach, the company increased online revenue by 11% - a tangible demonstration of how focusing illusions operate at organizational levels. Companies, like individuals, fall victim to overweighting salient information while undervaluing context they're not currently observing.

Social media amplifies these effects exponentially. Platforms curate feeds to showcase peak moments - vacations, achievements, purchases - while concealing the mundane reality that constitutes most of daily life. This creates a collective focusing illusion where everyone compares their full experience against everyone else's highlight reel. The result? Widespread dissatisfaction rooted in fundamentally distorted comparisons.

Understanding why the focusing illusion occurs requires examining how human attention and memory actually function. Our brains evolved to identify and respond to immediate threats and opportunities, not to hold dozens of variables in working memory simultaneously. When evaluating future scenarios, we construct mental simulations, but these simulations necessarily simplify reality by emphasizing certain elements while background details fade.

Affective forecasting research identifies several specific mechanisms behind prediction errors. First, we rely heavily on our current emotional state when imagining the future - if you're feeling optimistic today, you'll project that optimism forward; if you're anxious, future scenarios look bleaker. Second, we underestimate our own emotional resilience and adaptation capacity. The same psychological immune system that helps us recover from setbacks also diminishes positive experiences faster than we expect.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, we engage in what psychologists call immune neglect - we forget that our minds actively work to rationalize and adjust to new circumstances. When contemplating a job loss, we don't factor in how we'll reframe the experience as an opportunity, find silver linings, or develop new skills. When imagining a promotion, we don't account for new stressors, increased expectations, or how quickly the novelty will wear off.

The focusing illusion intensifies when we examine memories of past experiences. Research on life satisfaction demonstrates that we evaluate past events through a distorted lens, emphasizing peak moments and endings while averaging out the day-to-day experience. This creates a feedback loop: distorted memories inform flawed predictions, which create new experiences we'll later misremember, perpetuating the cycle.

The focusing illusion influences virtually every significant decision category. Career choices represent a prime example. People routinely overestimate how much a new job, promotion, or career change will affect their overall happiness. A study on happiness expectations found that younger adults particularly overestimated future happiness changes, though this improved somewhat with age and experience.

Consider someone accepting a higher-paying position with a longer commute. During the decision process, the salary increase dominates their thinking - they imagine all the things they'll buy, the financial security, the status upgrade. What they systematically underweight is the daily reality of spending three hours in traffic, arriving home exhausted, having less time for relationships and hobbies. Six months later, they've adapted to the higher income (thanks to lifestyle inflation), but the commute grinds on them every single day. They've made a focusing illusion-driven decision that reduced their quality of life.

Geographic relocations follow similar patterns. The promise of better weather, lower costs, or proximity to family/opportunities looms large during the decision phase. What fades from focus: the social networks you'll leave behind, the effort required to rebuild connections, the stress of navigating unfamiliar systems, and the countless environmental factors you take for granted in your current location. Climate studies famously demonstrate that people consistently overestimate how much weather affects life satisfaction - Californians aren't substantially happier than Midwesterners, though nearly everyone predicts they would be.

Consumer spending offers perhaps the clearest evidence of focusing illusion effects. We overpredict how much pleasure we'll derive from purchases, especially lifestyle upgrades. The psychology of affective forecasting errors explains why shopping provides such temporary satisfaction - we focus on the acquisition while ignoring how quickly we'll adapt to owning the item. That luxury car delivers excitement for weeks, maybe months, before becoming simply "the car you drive."

Your wellbeing depends far more on your adaptation mechanisms than on external circumstances matching predicted ideals.

Relationship decisions carry particularly high stakes when influenced by the focusing illusion. Someone might stay in an unfulfilling relationship because they overestimate the emotional devastation of being single. Conversely, others leave stable partnerships because they fixate on specific irritating behaviors while taking positive aspects for granted. Research from Mile High Psychiatry documents how people delay ending toxic relationships specifically because they overpredict the intensity and duration of post-breakup suffering.

Overcoming the focusing illusion requires actively building habits that counteract our natural cognitive tendencies. The first and most powerful tool: seek out actual data from people who've made similar decisions. Before accepting a job, talk to people who already work there - not just about the exciting projects, but about the daily grind. Before relocating, spend extended time in the new location during different seasons. Before making major purchases, research buyer experiences six months or a year post-purchase, not during the honeymoon period.

Billy Oppenheimer's analysis captures this perfectly through William James's concept: "The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook." The focusing illusion represents the opposite - fixating on what we shouldn't while overlooking what matters most. Wisdom involves deliberately broadening your aperture of attention.

Practical strategies for combating this bias include keeping a "prediction journal" where you record your expectations about decisions and their actual outcomes. This creates an evidence-based feedback loop that calibrates future predictions. Psychology research suggests that people who regularly reflect on past prediction errors become significantly better at forecasting, though complete accuracy remains elusive.

Another effective technique: force yourself to list everything that will remain unchanged after a major decision. If you're considering a career change, write down all aspects of your life that won't improve - your relationships, health challenges, personal anxieties, leisure activities. This exercise counteracts the focusing illusion by reintroducing neglected context. It doesn't mean rejecting change, but rather calibrating expectations realistically.

Mindfulness practices offer a complementary approach by training attention to notice present-moment experience rather than constantly projecting into imagined futures. When you catch yourself thinking "I'll be happy when [X happens]," pause and examine what you're neglecting in that formulation. What other factors contribute to your wellbeing? What will remain constant regardless? How have past predictions in this category performed?

Here's where this gets genuinely weird: knowing about the focusing illusion doesn't make you immune to it. Even Daniel Kahneman, who dedicated his career to studying these biases, acknowledged falling victim to them regularly. The phenomenon operates at such a fundamental level of cognitive processing that conscious awareness provides only limited protection.

"The good news is that understanding how affective forecasting works can help you make more grounded, emotionally informed choices and avoid being misled by your own expectations."

- Mile High Psychiatry

However, understanding the bias does change how you respond to your own predictions. Instead of treating your forecasts as reliable data, you learn to view them with appropriate skepticism. When you catch yourself thinking "This promotion will change everything," you can now counter with: "This is probably the focusing illusion talking. The promotion will change some things, likely less than I think, and for a shorter duration than I expect."

This meta-awareness shifts decision-making from prediction-based to systems-based thinking. Rather than trying to forecast whether something will make you happy, you examine whether it aligns with your values, fits your constraints, and moves you toward desired long-term patterns. Instead of asking "Will I be happy in California?", you ask "Does this move align with my priorities, and am I prepared for the adaptation period?"

The most sophisticated version of this approach involves recognizing that happiness itself might be the wrong metric. Research on life satisfaction increasingly suggests that meaning, engagement, relationships, and accomplishment predict wellbeing better than moment-to-moment happiness. When you stop chasing predicted emotional states and start building systems that generate sustainable satisfaction, the focusing illusion loses much of its power.

We're living through an unprecedented era of choice abundance. Previous generations faced constrained options for careers, locations, partners, and lifestyles. Limited choice simplified decision-making, even if it restricted freedom. Today's expanded possibility space amplifies the focusing illusion's impact - with more options to evaluate, we make more prediction errors, experience more regret, and waste more energy second-guessing decisions.

Social media creates a feedback loop that intensifies these effects. We're not just predicting how choices will affect us; we're predicting how they'll appear to others, adding another layer of focusing illusion. The curated highlights we see from others' lives establish unrealistic comparison points that skew our predictions even further from reality.

The economic implications extend beyond individual decisions. Entire industries exploit the focusing illusion systematically. The self-improvement market generates billions by suggesting that specific products, techniques, or transformations will have life-changing impacts. The lifestyle industry sells curated aesthetics by implying that matching their style will generate similar feelings. Marketing at every level relies on encouraging narrow focus while obscuring broader context.

Political messaging increasingly weaponizes this bias, framing complex policy choices around single emotionally resonant factors while obscuring tradeoffs and systemic effects. Understanding the focusing illusion doesn't just improve personal decisions - it creates some immunity to manipulation across domains.

The solution isn't to stop planning or imagining the future. Forecasting remains essential for navigating life. But we can develop a more sophisticated relationship with our predictions by treating them as provisional hypotheses rather than reliable prophecies.

When making significant decisions, try the "and then what?" exercise. You imagine getting the promotion - and then what? You enjoy it for a while - and then what? The novelty fades - and then what? This forces attention beyond the initial change to the longer-term equilibrium state that will actually constitute your lived experience.

Consider adopting what psychologists call "satisficing" rather than maximizing - choosing options that meet your criteria rather than endlessly searching for optimal solutions. Maximizers experience more decision regret because they overpredict how much better the "perfect" choice would have been. Satisficers face less disappointment because they set realistic thresholds rather than pursuing predicted perfection.

Perhaps most importantly, recognize that your current self is probably reasonably satisfied with circumstances your past self would have considered suboptimal. That reveals a crucial truth: your wellbeing depends far more on your adaptation mechanisms than on external circumstances matching predicted ideals. The focusing illusion blinds us to our own resilience and adaptability.

Here's the one prediction about your future that research consistently validates: you'll adapt to whatever circumstances you encounter faster and more completely than you currently imagine. Whether facing setbacks or achieving goals, you'll adjust. The emotional intensity you're projecting - whether anxiety or anticipation - will fade more quickly than it seems possible right now.

This isn't pessimism about positive changes or optimism about negative ones. It's realism about psychological processes. Understanding this pattern doesn't mean treating all choices as equivalent - some decisions genuinely improve objective circumstances and long-term trajectories. But it does mean recognizing that happiness emerges more from how you process experiences than from the experiences themselves matching predicted forms.

The focusing illusion reveals both a limitation and a liberation. Yes, your predictions are systematically biased, and you'll continue making errors despite knowing better. But you're also far more adaptable, resilient, and capable of generating satisfaction from varied circumstances than you give yourself credit for. The future will likely differ from your predictions - but you'll probably be fine either way.

The next time you catch yourself convinced that one change will transform everything, pause and consider: you're standing in the future your past self predicted, probably inaccurately. Yet here you are, adapting, continuing, finding sources of satisfaction your previous self didn't anticipate. The pattern will continue. Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you're thinking about it - including this very insight.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

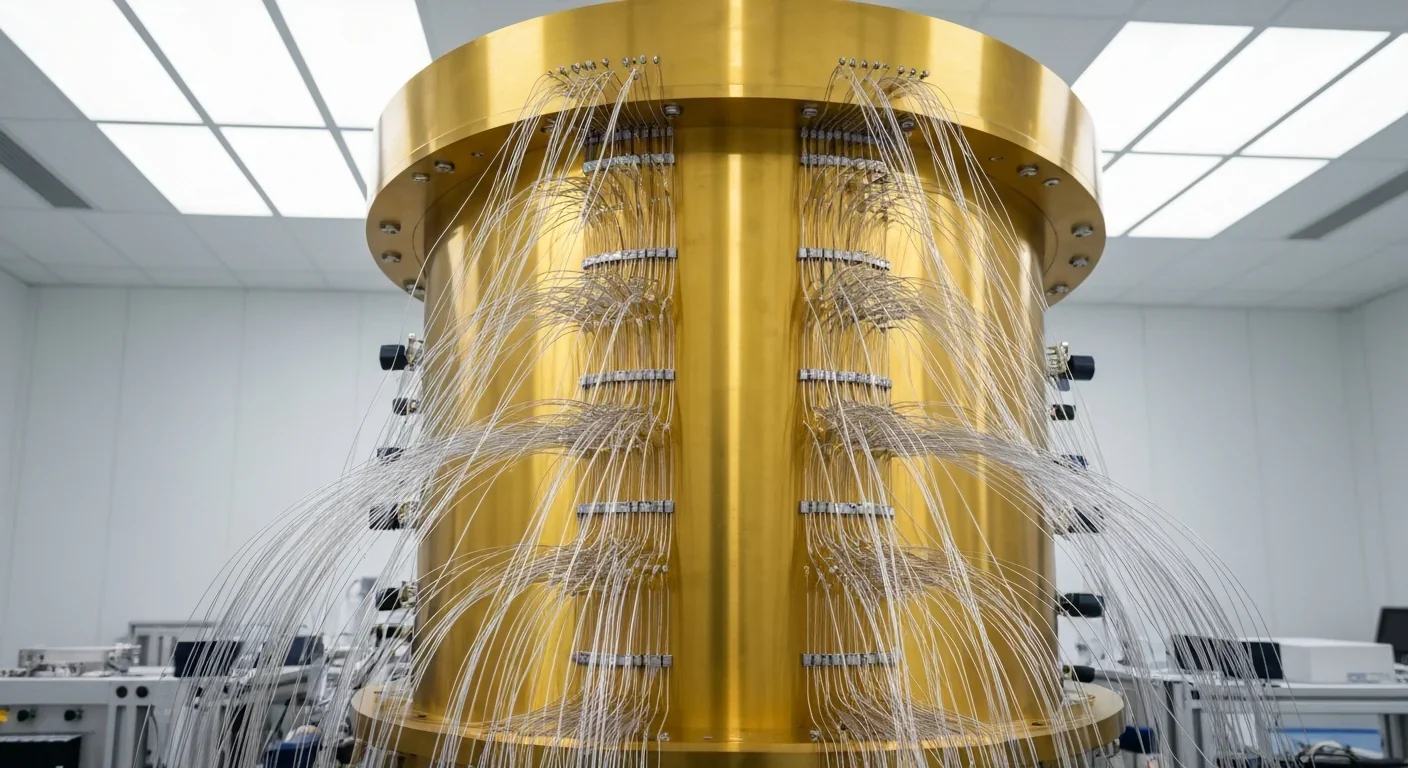

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.