The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Your brain's phonological loop - a working memory system designed to rehearse auditory information - creates earworms by trapping musical fragments in endless repetition cycles. Understanding why certain songs stick and using evidence-based strategies like moderately difficult tasks or chewing gum can help you regain control.

You're halfway through an important presentation when it hits you again - that same three-second snippet from last night's pop song, looping endlessly through your mind. You can't make it stop. You try focusing harder on your slides, but your brain keeps serving up that chorus like a broken record player nobody asked for. If you're wondering why your brain seems determined to torture you with musical fragments at the worst possible moments, neuroscience has answers - and they're stranger than you might think.

Welcome to the world of earworms, those sticky musical fragments that lodge themselves in your consciousness and refuse to leave. Scientists call them involuntary musical imagery, and about 90% of us experience them at least once a week. But earworms aren't random glitches in your mental software. They're the result of a specific brain system - your phonological loop - getting hijacked by music in ways researchers are only beginning to understand.

Deep in your working memory sits a component called the phonological loop, and it's largely responsible for why you can't get that song out of your head. Think of it as your brain's temporary voice recorder, designed to hold onto spoken or heard information just long enough for you to use it.

The phonological loop has two parts working in tandem. The first is the phonological store - what researchers call the "inner ear" - which holds speech-based information for about one to two seconds. The second component is the articulatory rehearsal system, your "inner voice," which silently repeats sounds to keep them in working memory. It's this inner voice that keeps replaying that chorus whether you want it to or not.

Here's where things get interesting. Your phonological loop normally processes about seven items (give or take two) for those brief one to two seconds. Written information has to be converted into an auditory code before entering this system. Once it's in, the articulatory rehearsal kicks in, creating what amounts to a mental recording loop.

Your phonological loop can hold about 7 items for just 1-2 seconds, but that's enough time for a catchy musical phrase to get trapped in an endless rehearsal cycle.

When a catchy musical phrase enters your phonological store, your brain's rehearsal system latches onto it. The fragment gets repeated, reinforced, and effectively trapped in a cycle that runs outside your conscious control. It's not that you're choosing to think about that song - your phonological loop is doing what it evolved to do, which is maintain auditory information through repetition.

Brain imaging studies show that tasks tapping into phonological storage activate the left-hemisphere perisylvian language areas, including the superior temporal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus. These regions reflect auditory cortical participation. When an earworm strikes, similar brain regions light up, suggesting your mind is essentially "hearing" the music even though no sound exists in the external environment.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that the phonological loop operates somewhat independently from your conscious attention. You can be focused on something entirely different - writing an email, having a conversation, trying to sleep - and that loop keeps running in the background, faithfully rehearsing those few seconds of melody.

Not all music has equal earworm potential. Certain characteristics make some songs far more likely to lodge themselves in your phonological loop, and researchers have identified several patterns.

Repetitive, simplistic, and catchy tunes top the list. Your brain is wired to recognize patterns, and repetitive music creates neural loops that reinforce memory and familiarity. The more a song repeats a particular phrase or melodic pattern, the more easily that pattern embeds itself in your working memory system.

Studies published in the British Journal of Psychology found that earworms typically last 15 to 30 seconds - just long enough to exceed the phonological store's natural one to two second window, which means the fragment requires active rehearsal to maintain. This creates the loop. The song snippet is too long to simply fade away but short enough to cycle through your rehearsal system repeatedly.

Musical training matters too. Research shows earworms are more common in people with musical backgrounds, likely because these individuals have more developed auditory imagery systems. Their brains are better at internally recreating musical sounds, which paradoxically makes them more susceptible to involuntary musical replay.

"People remember unfinished or interrupted tasks better than completed tasks."

- Bluma Zeigarnik, Psychology Researcher

The songs themselves often share common features. They tend to have upbeat tempos, simple melodic contours, and unexpected interval patterns that create a sense of incompleteness. That sense of something unfinished is crucial - it's related to what psychologists call the Zeigarnik effect, where people remember interrupted or incomplete tasks better than completed ones.

When you hear just part of a song, or when a song has an unusual melodic structure that feels incomplete, your brain generates task-specific tension. This tension improves the cognitive accessibility of the relevant memory contents. Your phonological loop keeps rehearsing the fragment, essentially trying to "complete" the unfinished auditory task. The problem is, with earworms, there's no real completion - the loop just keeps going.

Emotional connection amplifies stickiness. Songs tied to specific memories, moods, or personal experiences lodge more firmly in memory. If a particular tune played during a significant life event, or if it matches your current emotional state, your brain prioritizes it. This is why you might find yourself cycling through the soundtrack of a recent breakup or the theme song from a childhood show during moments of nostalgia.

When an earworm strikes, multiple brain regions collaborate to create the experience of hearing music that isn't there. Neuroimaging has revealed that musical imagery activates the auditory cortex, the same brain area that processes actual sounds you hear with your ears.

PET studies by Zatorre and colleagues demonstrated bilateral activation in the secondary auditory cortex during musical imagery. Participants imagining songs showed neural activity patterns remarkably similar to those perceiving actual music. This means when you "hear" that earworm playing in your head, your brain's auditory systems are genuinely active, processing imagined sound much like real sound.

The involvement goes beyond just auditory areas. Motor planning regions also activate during earworms, particularly areas like Broca's area associated with speech production and the articulatory control process. This makes sense - your inner voice is essentially a motor program, simulating the movements involved in speaking or singing even though you're not actually making sounds.

fMRI evidence shows the auditory cortex exhibits increased activation during earworm experiences. What's fascinating is that this activation can occur spontaneously, without conscious effort to imagine music. Your phonological loop can initiate and maintain the auditory imagery independently, which explains why earworms feel intrusive and involuntary.

When you experience an earworm, your auditory cortex activates just as if you were actually hearing the music - your brain can't tell the difference between imagined and real sound.

The prefrontal cortex, involved in executive control and attention, also plays a role - though perhaps not the one you'd hope for. When cognitive resources are limited or when you're not actively engaged in demanding tasks, the prefrontal cortex's ability to suppress spontaneous phonological rehearsal weakens. This creates the perfect conditions for earworms to emerge.

This neural setup creates a positive feedback loop. The auditory cortex generates the musical image, the motor areas support the rehearsal, and the weakened executive control fails to suppress it. The phonological loop keeps cycling, and you're stuck with your unwanted soundtrack.

Earworms don't attack randomly. They have preferred conditions, and understanding these triggers helps explain why certain moments seem particularly vulnerable to musical invasion.

Low cognitive load states - periods when you're not mentally taxed - are prime earworm territory. When you're bored, doing routine tasks, or letting your mind wander, your working memory resources aren't fully engaged. With your central executive not occupied, your phonological loop has free rein to rehearse whatever auditory material happens to be accessible.

Research indicates our brains spend up to 40% of our time on thoughts unrelated to present tasks. During these mind-wandering episodes, earworms flourish. The shower, the morning commute, falling asleep - these low-demand activities create perfect conditions because your phonological loop can operate without competition from other cognitive processes.

Stress and mood play significant roles too. Studies show earworms are linked to neuroticism and obsessive-compulsive traits. Stress reduces available working memory resources, which means your central executive has less capacity to suppress spontaneous rehearsal. When you're anxious or stressed, you're more vulnerable to intrusive thoughts of all kinds, including musical ones.

Recent or repeated exposure matters enormously. University of London researchers found that hearing a song repeatedly is one of the primary triggers for earworms. The more times a musical pattern passes through your phonological loop, the more accessible it becomes. Radio hits become earworm candidates precisely because you've heard them multiple times, each exposure strengthening the neural trace.

"Our brains spend up to 40% of our days thinking thoughts that are unrelated to our present task at hand."

- Cognitive Research Study

Specific memories and associations also trigger earworms. Hearing a song that reminds you of a person, place, or event can reactivate the musical memory. Your brain's associative networks link the tune to the memory, and when one gets activated, the other follows. This is why seemingly random cues - a smell, a location, a phrase someone says - can suddenly launch an earworm.

Personality matters too. Research with Iranian college students found that while 90% of participants experienced earworms at least weekly, frequency varied with personality traits. People high in neuroticism reported more frequent and more bothersome earworms. The correlation suggests that individual differences in how our working memory systems operate influence earworm susceptibility.

The good news is that understanding the phonological loop's role in earworms points toward genuine solutions. Several strategies have research backing, and they all work by disrupting the rehearsal mechanism or replacing it with something else.

Engaging in moderately difficult cognitive tasks is one of the most effective approaches. Scientists at Western Washington University found that activities like solving anagrams, working on puzzles, or reading complex material reduced earworm recurrence. These tasks engage your working memory just enough to prevent the phonological loop from idly rehearsing music, but not so much that they become overwhelming.

The key is moderate difficulty. Tasks that are too easy won't occupy enough cognitive resources, leaving room for the earworm to continue. Tasks that are too hard can increase stress, which might actually worsen the problem. Finding that sweet spot - what psychologist Ira Hyman calls "not too easy, but not too difficult" - gives your phonological loop something productive to do instead of recycling that chorus.

Here's where things get weird: chewing gum actually works. Research from the University of Reading found that participants who chewed gum while trying not to think about a specific song thought about it only seven times on average, compared to ten times for non-chewers. The motor activity of chewing interferes with the articulatory rehearsal component of your phonological loop.

Research shows chewing gum reduces earworm frequency by 30% - the motor activity interferes with your brain's ability to rehearse music internally.

Your inner voice relies on motor planning regions that simulate speech movements. When you co-opt those same motor systems for chewing, you create interference. The neural resources needed for subvocal rehearsal get partially occupied by the physical act of chewing, making it harder for the earworm to maintain its loop. It sounds strange, but the data supports it.

Listening to a different song - ideally a less catchy one - provides a replacement strategy. The idea is to give your phonological loop something else to work with. Some researchers suggest choosing a particularly non-catchy tune as a replacement. The new music occupies the auditory working memory space, pushing out the previous earworm.

Alternatively, listening to the entire earworm song from start to finish might help. Remember the Zeigarnik effect - incomplete tasks persist in memory. By completing the song, you potentially relieve the cognitive tension that keeps the fragment looping. This doesn't work for everyone, and there's a risk it might reinforce the earworm instead, but for some people it provides closure.

There's also some evidence that singing the earworm aloud might help, though with a caveat: you might become what researchers jokingly call an "earworm carrier", passing the musical infection to anyone within earshot. If you're in a private space, externalizing the internal voice might help break the loop by shifting from involuntary imagery to voluntary production.

Before you curse your phonological loop, consider what it's actually doing. Earworms aren't purely annoying accidents of brain architecture. Emerging research suggests they might serve functions related to memory consolidation.

A 2021 study by Kubit and Janata had participants watch videos while listening to unfamiliar music. Later, when the music became an earworm, participants recalled more details from the videos. The more frequently the song became an earworm, the better their memory for associated information. When they listened to the music again, memory recall reached near-perfect levels.

This suggests that your phonological loop's repetitive rehearsal might be strengthening memory traces, helping consolidate new experiences. The earworm isn't just replaying the music - it's potentially reinforcing connections between the music and other information encoded at the same time. As Dr. Benjamin Kubit noted, "earworms are more than just an irritation" - they may be a natural memory consolidation process.

"Earworms are more than just an irritation - they may be a natural memory consolidation process."

- Dr. Benjamin Kubit, Cognitive Neuroscientist

Your phonological loop evolved to help you maintain and manipulate auditory information. Being able to hold speech sounds in working memory is crucial for language comprehension, learning, and communication. The fact that this system occasionally latches onto music and won't let go is perhaps an inevitable side effect of having such a powerful auditory memory mechanism.

The persistence of earworms also tells us something about how efficiently our brains process patterns. Your phonological loop can identify, store, and rehearse complex auditory patterns with minimal conscious involvement. That's actually remarkable. The system works so well that sometimes it works too well, maintaining patterns you didn't ask it to maintain.

Understanding earworms changes how we think about consciousness and control. These involuntary musical experiences reveal that significant chunks of our mental activity operate outside conscious direction. Your phonological loop doesn't need your permission to rehearse auditory information. It just does it, following its own algorithms and priorities.

The prevalence of earworms - affecting 98% of people according to some studies - reminds us that certain aspects of mental experience are universal. Across cultures, backgrounds, and musical preferences, our brains share this tendency to create spontaneous auditory loops. It's part of what makes us human, for better or worse.

Gender differences add another wrinkle. Research by James Kellaris found that while women and men experience earworms equally often, they last longer for women and tend to irritate them more. Whether this reflects genuine differences in phonological loop functioning or differences in how the phenomenon is reported and experienced remains an open question.

The next time an earworm hijacks your consciousness, you'll at least know what's happening. Your phonological loop is doing its job - maintaining auditory information through rehearsal. It's not a bug in your mental software. It's a feature that occasionally runs when you'd rather it didn't.

And if understanding doesn't make it any less annoying, well, there's always chewing gum.

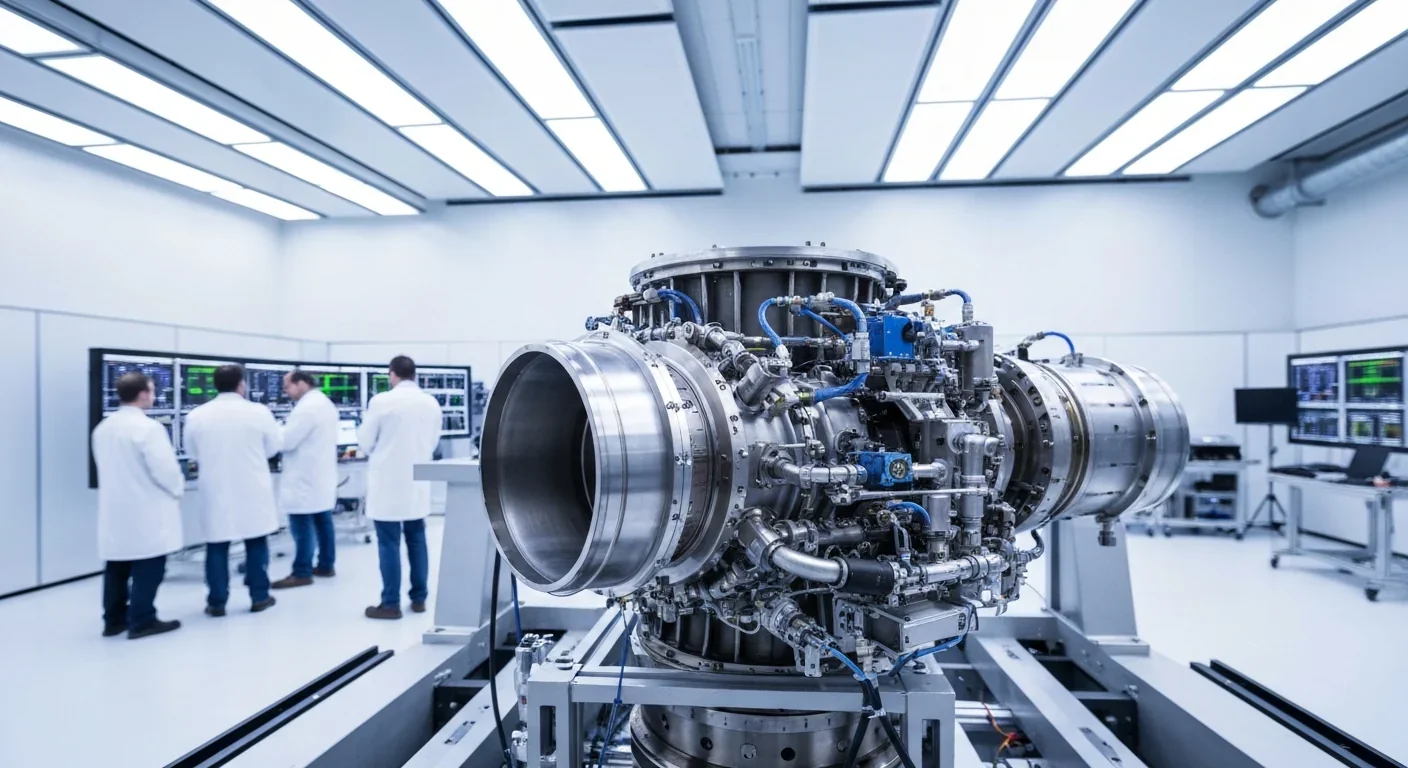

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

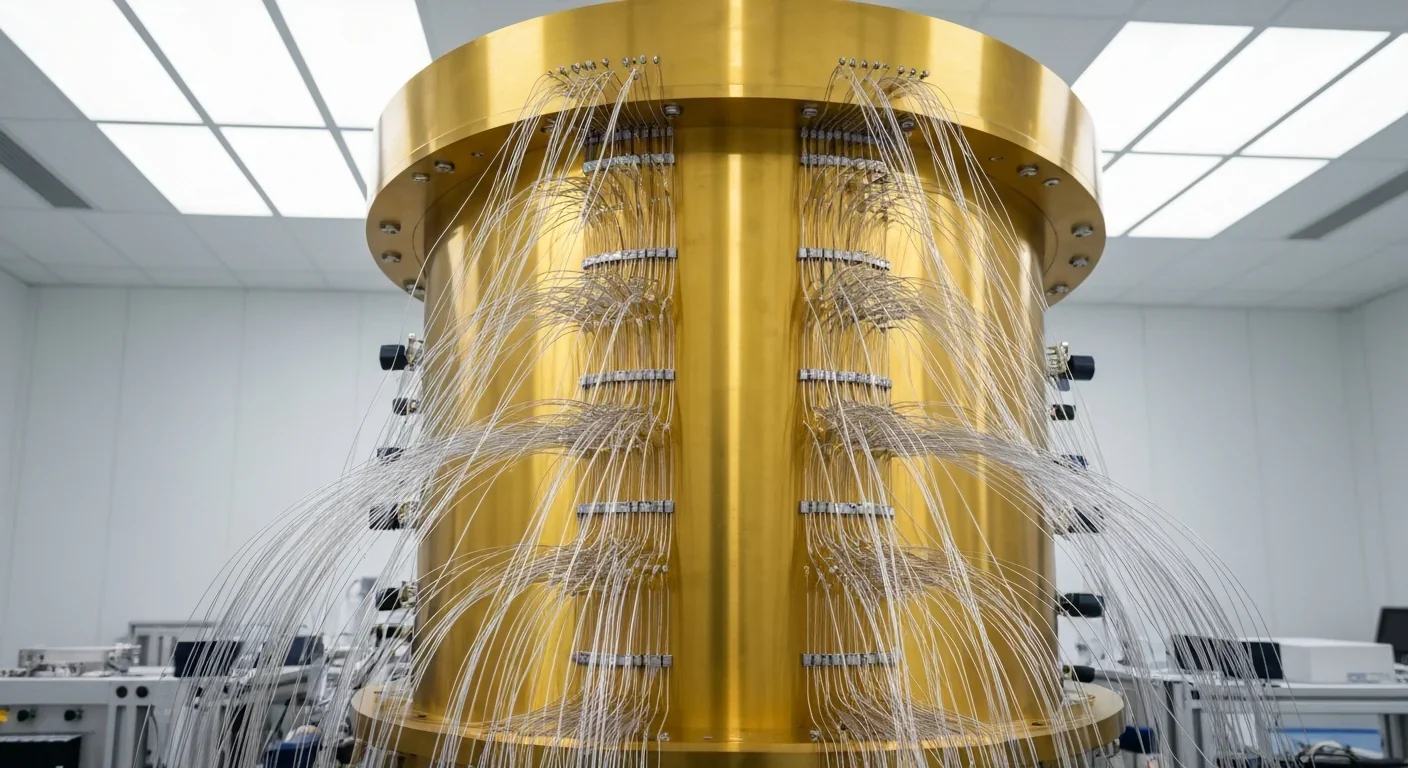

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.