Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Half of people miss a gorilla walking through their visual field due to change blindness and inattentional blindness. These perceptual limitations affect driving safety, medical diagnoses, and eyewitness testimony, but understanding them helps us develop strategies to see better.

You're certain you see everything in front of you. After all, your eyes are open, you're paying attention, and the world appears crystal clear. But what if I told you that half of people miss a person in a gorilla suit walking through their field of vision? Not hidden in shadows or lurking at the edges, but strolling directly through the center of their gaze, thumping its chest for emphasis.

This isn't a glitch in our eyes. It's a feature of how our brains process reality, and it affects everything from driving safety to eyewitness testimony. Welcome to the world of change blindness and inattentional blindness, where the limits of human perception meet the demands of modern life.

In 1999, psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris created a deceptively simple experiment. They filmed two teams passing basketballs and asked viewers to count the passes made by one team. Halfway through the 24-second video, a person in a full gorilla costume walked into the frame, stopped in the center, beat their chest, and walked off. The gorilla appeared for nine full seconds.

The results shocked researchers. Roughly 50% of participants completely failed to notice the gorilla, despite it occupying the center of the screen. When shown the video again without the counting task, participants refused to believe it was the same footage. Some accused researchers of switching videos.

The invisible gorilla experiment revealed something profound: we don't actually see everything in our visual field. Instead, our brains construct a selective version of reality based on what we're focusing on.

Later research at the University of Utah replicated these findings with 197 participants, discovering that detection rates varied dramatically based on working memory capacity. Participants with high working memory noticed the gorilla 67% of the time, while those with low working memory spotted it only 36% of the time. You're literally twice as likely to see unexpected changes if your brain has more attentional resources available.

Our visual system processes an overwhelming amount of information every second. The human eye contains roughly 126 million photoreceptor cells, each sending signals to the brain. If we consciously processed all this data, we'd be paralyzed by information overload.

Evolution solved this problem with a shortcut: selective attention. Your brain creates what researchers call an "attentional set," a filter that prioritizes information relevant to your current goals while suppressing everything else. When you're counting basketball passes, your attentional set focuses on the movement of the ball and the players in specific colors. Everything else, including gorilla-suited intruders, gets filtered out before reaching conscious awareness.

This isn't a design flaw. For most of human evolutionary history, this filtering system kept our ancestors alive. When hunting prey or avoiding predators, the ability to focus intensely on relevant details while ignoring distractions meant the difference between eating and being eaten. The problem is that our Stone Age brains now operate in environments where the unexpected can appear anywhere, at any time.

Modern neuroscience research using fMRI scanning has revealed the neural mechanisms behind this phenomenon. When participants focus on demanding tasks, the primary visual cortex shows reduced activation in response to unexpected stimuli. Your brain isn't just ignoring the gorilla at a conscious level - it's actively suppressing visual processing of irrelevant information at the neural level.

The effect becomes even more pronounced under high cognitive load. Research shows that when participants manipulated verbal material during visual tasks, they missed unexpected visual stimuli far more often than in low-demand conditions. The more mental resources you dedicate to one task, the fewer you have available to detect changes in your environment.

The invisible gorilla is amusing in a laboratory setting. In the real world, these perceptual blind spots kill people.

Traffic accidents caused by blind spot failures claim thousands of lives annually. But the problem isn't always physical blind spots created by car design. Often, drivers look directly at motorcycles, pedestrians, or other vehicles and simply fail to see them because their attention is focused elsewhere - on navigation, conversation, or internal thoughts.

"Our prior research has shown that very few individuals - only 2.5 percent - are capable of handling driving and talking on a cell phone without impairment."

- David L. Strayer, University of Utah

Research by David Strayer at the University of Utah found that only 2.5% of people can drive and talk on a cell phone without significant impairment. The other 97.5% experience inattentional blindness, missing traffic signals, pedestrians, and vehicles they're looking directly at. Their eyes work fine. Their attention is simply occupied by the conversation, leaving insufficient cognitive resources to process unexpected visual events.

The stakes are equally high in medicine. In a striking 2013 study, researchers embedded an image of a gorilla - 48 times larger than a typical cancer nodule - into lung CT scans. They asked 24 radiologists to review the scans for lung nodules. 83% of the radiologists missed the gorilla entirely, despite eye-tracking data showing many looked directly at it. When you're searching for small white nodules, even a massive gorilla becomes invisible.

This finding rattled the medical imaging community because it revealed a fundamental limitation in human perception that training alone cannot overcome. The more expert you become at a specialized task, the more your attentional set narrows to expected patterns, making unexpected anomalies harder to detect.

While inattentional blindness occurs when we fail to notice unexpected objects, change blindness happens when we miss alterations to things we've already seen. The two phenomena share similar neural mechanisms but manifest differently.

In change blindness experiments, participants fail to detect substantial modifications to images or scenes when changes occur during visual disruptions - eye movements, brief blanks, or shifts in camera angle. Buildings disappear, clothing changes color, entire objects swap positions, and most people notice nothing.

One famous real-world demonstration involved researchers approaching pedestrians to ask for directions. Mid-conversation, two workers carrying a door would pass between the researcher and the pedestrian, and a different researcher would swap places behind the door. Nearly half of participants failed to notice they were now talking to a completely different person.

The explanation lies in how our brains construct visual memory. We don't store detailed snapshots of everything we see. Instead, we retain a sparse representation of the scene - enough to recognize it as "a person asking for directions" - without encoding specific facial features unless we're actively attending to them.

Research published in Frontiers in Cognition demonstrated that detecting multiple simultaneous changes is even more challenging than detecting single changes. When several elements of a scene change at once, our visual working memory becomes overwhelmed, and detection accuracy plummets. This has significant implications for safety in complex visual environments like cockpits, control rooms, and busy intersections.

Perhaps nowhere are the stakes of perceptual blindness higher than in criminal justice. Eyewitness misidentification remains the leading cause of wrongful convictions, contributing to more than 70% of overturned convictions.

In 1995, Boston police officer Kenneth Conley was chasing a shooting suspect when he ran directly past a violent assault on another officer. Conley insisted he never saw the fight, leading to perjury charges and conviction. Years later, researchers recognized his case as a textbook example of inattentional blindness. While focused intensely on his pursuit target, his brain filtered out even a brutal attack happening in his direct line of sight.

The weapon focus effect demonstrates another dimension of this problem. When a weapon is present during a crime, witnesses fixate on the weapon rather than the perpetrator's features, resulting in dramatically reduced recall accuracy for facial details. Attention narrows to the threat, and everything else becomes secondary.

A 1974 experiment showed 2,145 viewers a 13-second robbery clip. When asked to identify the perpetrator, responses were essentially random. Nearly 2,000 witnesses can be wrong.

A 1974 experiment by Robert Buckhout drove this point home. He showed 2,145 viewers a 13-second clip of a mock robbery, then asked them to identify the perpetrator from a lineup. Responses were essentially random - approximately equal numbers picked suspects 1, 2, and 5, with 25% saying the perpetrator wasn't in the lineup at all. Nearly 2,000 witnesses can be wrong, and often are.

Legal systems are slowly adapting to this reality. The 2024 Court of Appeals decisions reflect growing judicial scrutiny of eyewitness evidence, with courts increasingly requiring experts to explain memory limitations to juries. Some jurisdictions now mandate specific lineup procedures and jury instructions that acknowledge the fundamental unreliability of human perception.

Interestingly, people with ADHD perform better on inattentional blindness tasks than neurotypical controls. Their difficulty maintaining focused attention on the primary task means they retain more awareness of peripheral stimuli. What's labeled a deficit in one context becomes an advantage in another.

Working memory capacity also plays a crucial role. As the University of Utah research demonstrated, individuals with higher working memory can juggle more information simultaneously, leaving spare attentional resources for unexpected events. If you're good at paying attention, you're twice as likely to notice the gorilla.

Age affects perceptual awareness too. Younger adults generally detect changes more reliably than older adults, though this varies significantly based on the type of change and the familiarity of the environment.

Expertise in specific domains can be both blessing and curse. Radiologists develop extraordinary skill at detecting subtle anomalies in expected locations but become more vulnerable to missing obvious anomalies in unexpected places. Their attentional sets become so finely tuned to specific patterns that anything outside those patterns becomes effectively invisible.

If our perceptual limitations are hardwired, are we doomed to miss gorillas forever? Not exactly. While we can't eliminate these effects entirely, we can develop strategies to compensate.

The cognitive interview technique used by trained investigators dramatically improves eyewitness recall accuracy. Rather than standard questioning, the method uses structured prompts that guide witnesses through multiple retrieval strategies, accessing memories from different angles. This approach doesn't eliminate perceptual blind spots, but it does help people recover more of what they actually encoded.

Recent research suggests that training focused on distractor filtering efficiency can increase visual working memory capacity. Participants who practiced filtering irrelevant information while maintaining awareness of relevant details showed measurable improvements in change detection. The brain's attentional systems have some plasticity.

"If you are on task and counting passes correctly, and you're good at paying attention, you are twice as likely to notice the gorilla compared with people who are not as good at paying attention."

- Jason M. Watson, University of Utah

Metacognitive awareness helps too. Understanding that you have perceptual blind spots makes you more likely to double-check assumptions. Pilots use standardized checklists not because they're forgetful, but because they understand human attention is fallible. The same principle applies to surgeons, nuclear power plant operators, and anyone working in high-stakes environments.

For everyday life, practical strategies include:

Eliminate divided attention during critical tasks. Put down your phone when driving, walking in traffic, or operating machinery. Your brain cannot fully attend to multiple streams of information simultaneously.

Use external aids. Blind spot monitoring systems in vehicles compensate for perceptual limitations, detecting vehicles you might miss. Checklists catch steps you might overlook.

Pause and scan deliberately. Before pulling into traffic, take an extra second to scan specifically for motorcycles and bicycles - the road users most often missed. Explicitly looking for the unexpected reduces inattentional blindness.

Question your certainty. The most dangerous phrase in perception research is "I would have noticed." You wouldn't have, and neither would anyone else.

As artificial intelligence systems increasingly augment human decision-making, understanding our perceptual limitations becomes critical. AI doesn't experience inattentional blindness the way humans do, but it has its own blind spots based on training data and algorithms.

The most effective systems will combine human pattern recognition with machine vigilance, each compensating for the other's weaknesses. Radiologists paired with AI detection systems catch more anomalies than either alone. The same principle applies to autonomous vehicles, security monitoring, and air traffic control.

Magicians have exploited these perceptual gaps for centuries, creating wonder by manipulating attention and expectation. Now neuroscientists study magic tricks to understand the mechanics of consciousness itself. What feels like seeing everything is actually a constructed model of reality, built from sparse data and filled in with assumptions.

The invisible gorilla isn't just a party trick or a curiosity for psychology students. It's a window into how consciousness works - and more importantly, how it fails. Every day, we miss gorillas: the cyclist we nearly hit, the symptom we overlooked, the security threat we dismissed.

The first step to seeing better is admitting what we can't see. Your brain is filtering reality right now, deciding what deserves your attention and what doesn't. Most of the time, it guesses right. But when it guesses wrong, the consequences can be devastating.

So the next time you're absolutely certain you would have noticed, remember: fifty percent of people miss the gorilla. And most of them were just as certain as you are.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

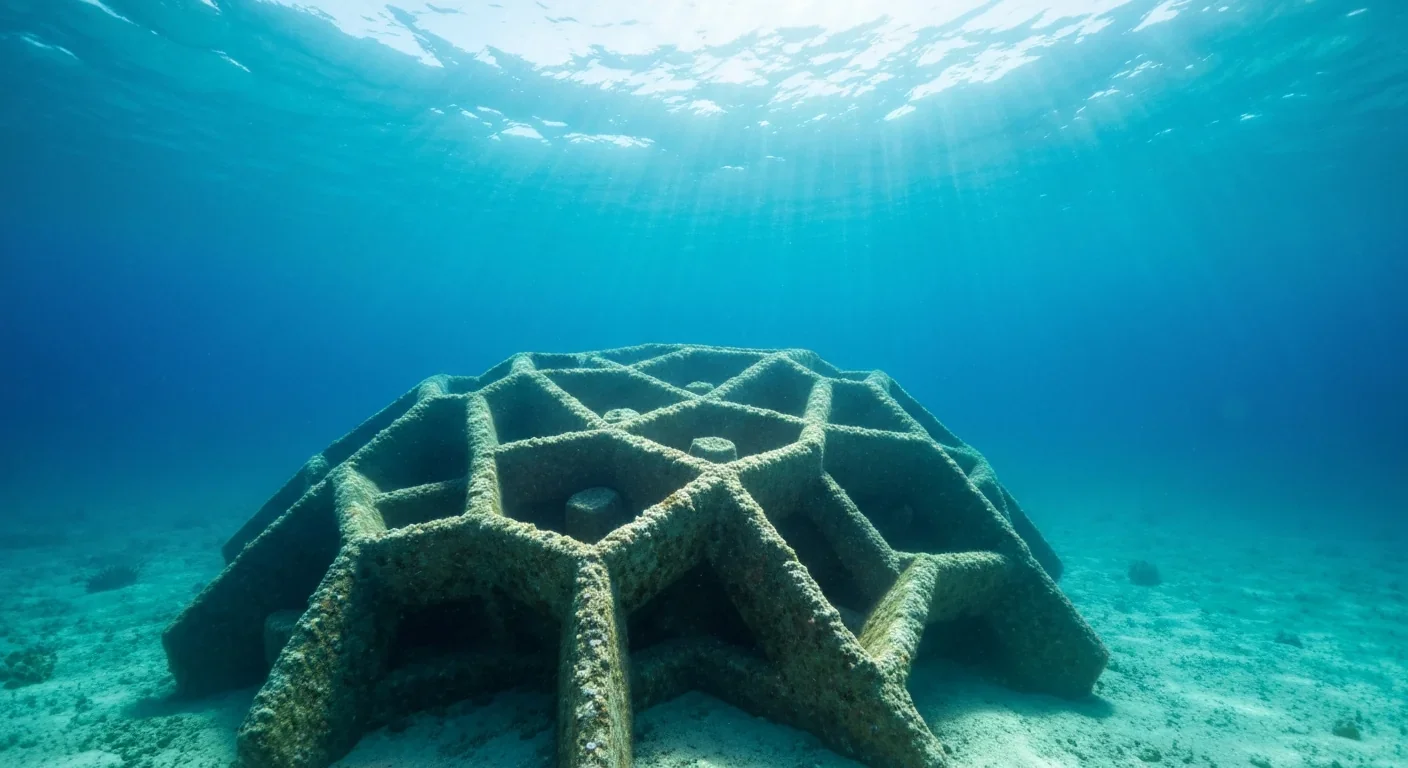

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

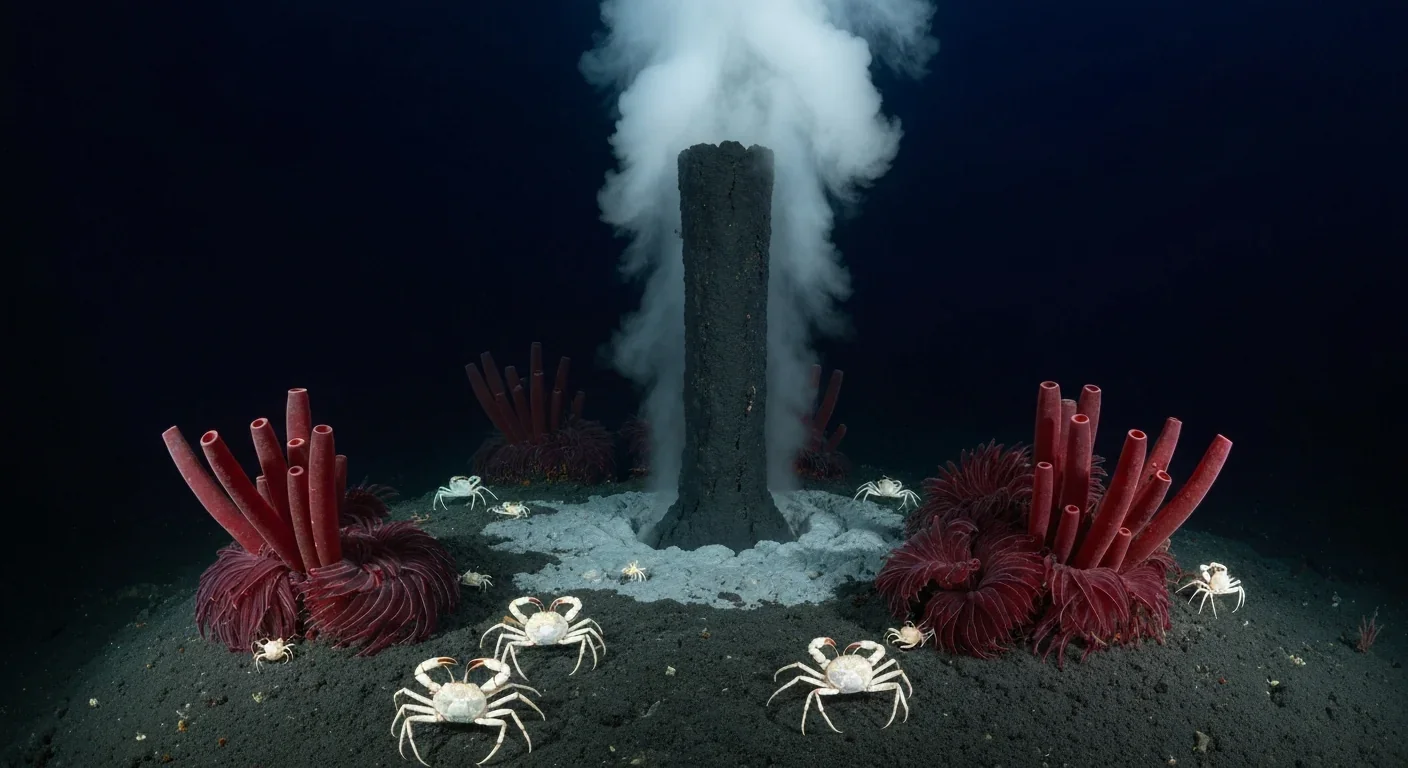

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

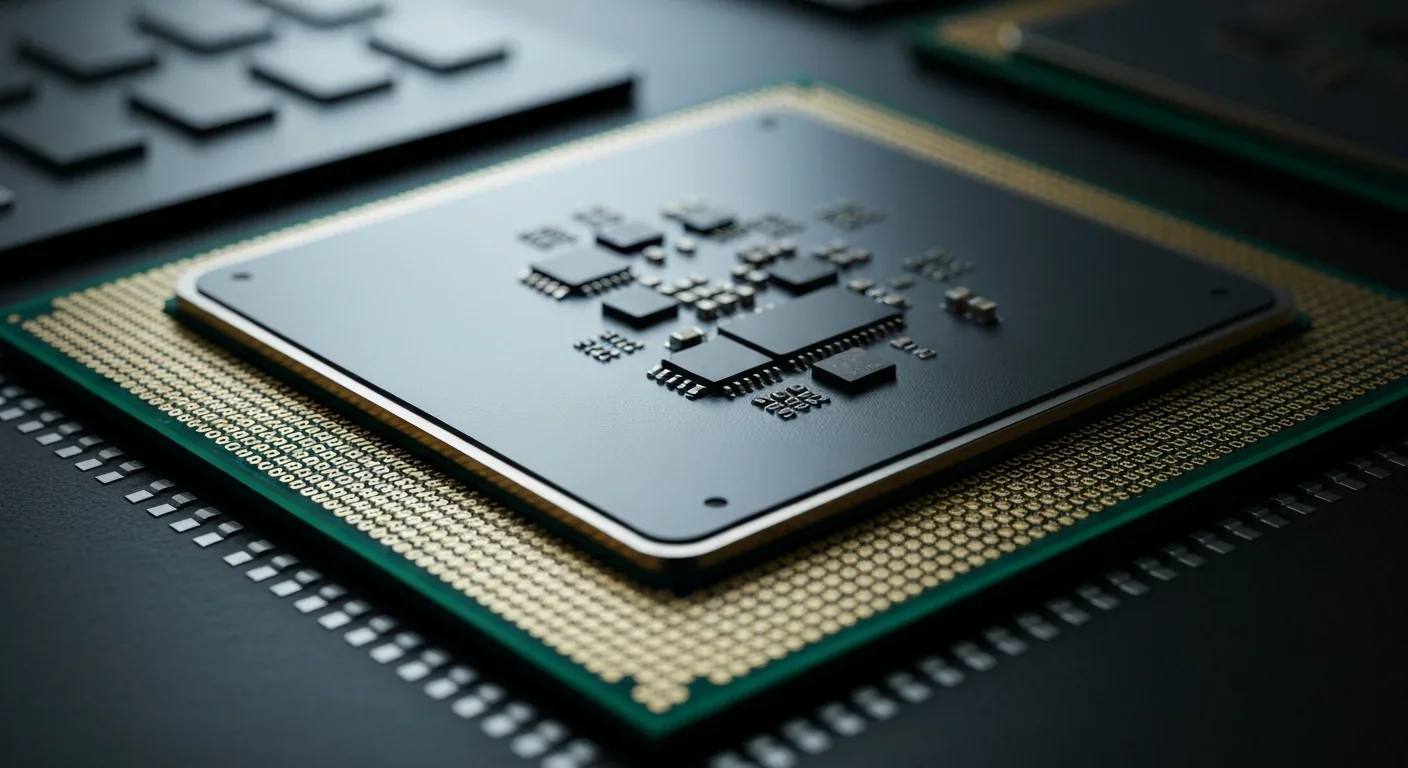

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.