The Science Behind Earworms: Brain's Musical Loop Explained

TL;DR: The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

What if the path to being more likable wasn't about hiding your flaws, but about revealing them at exactly the right moment? In 1966, a psychologist named Elliot Aronson discovered something that would challenge everything we think about perfection and social appeal. His research showed that highly competent people who made small, harmless mistakes became more attractive to others, not less. This counterintuitive finding, known as the pratfall effect, has profound implications for how we present ourselves at work, in leadership roles, and in everyday social interactions.

The discovery came from an elegantly simple experiment. Aronson had participants listen to recordings of actors pretending to be contestants on a quiz show. Some contestants answered 92% of difficult questions correctly and described impressive academic credentials. Others answered only 30% correctly and had mediocre backgrounds. At the end of some recordings, the contestant spilled a cup of coffee all over themselves. The results were striking: when the high-performing contestant made this clumsy mistake, their likability ratings shot up. When the average performer made the same mistake, their ratings dropped.

This wasn't a fluke. The effect has been replicated in multiple studies across different contexts, cultures, and decades. It's become a cornerstone of social psychology research on impression formation. But like many psychological phenomena, the pratfall effect comes with critical conditions. Understanding when it works and when it backfires can mean the difference between building connection and destroying credibility.

Why do we like competent people more after they mess up? Three psychological mechanisms work together to create this effect, each revealing something fundamental about human social behavior.

First, there's the humanizing effect. Highly competent people can seem intimidating or distant. They trigger social comparison processes that make us feel inadequate. When someone exceptional makes a mistake, it creates what psychologists call a threat reduction. Suddenly, they're not a walking reminder of our own limitations. They're human, just like us. This shift from perceived threat to perceived warmth is powerful. Research published in Frontiers in Health Services found that displays of vulnerability increase trust and closeness in interpersonal relationships.

The pratfall effect only works when you've already established competence. For those still proving themselves, mistakes hurt rather than help.

Second, the contrast effect amplifies the person's overall competence. When you've just watched someone ace a difficult quiz, a small blunder creates a sharp contrast that actually makes their competence more memorable and impressive. The mistake serves as a counterpoint that highlights how exceptional their performance was. It's like a single crack in a perfect diamond making you notice the clarity of everything else.

Third, vulnerability signals authenticity. In an age where everyone carefully curates their public image, genuine moments of imperfection stand out. They signal that someone isn't trying to manipulate how they're perceived. This authenticity creates the foundation for real social bonding. When a leader spills coffee during a presentation, it says: "I'm not performing for you. This is just me."

But here's where it gets interesting. The pratfall effect operates on what psychologists call a competence prerequisite. You must first be seen as highly capable for a mistake to boost your appeal. If you're already perceived as incompetent or average, the same blunder will decrease your likability. This creates an asymmetric pattern: mistakes help those who least need help and hurt those who most need it.

The severity of the mistake matters enormously. A 1972 study by Mettee and Wilkins systematically varied the magnitude of blunders to map out the boundaries of the effect. They found that minor pratfalls barely decreased respect while significantly increasing liking for highly competent individuals. Major blunders, interestingly, produced an even larger boost in likability, though they did reduce respect somewhat.

This creates a strategic consideration: the bigger the mistake (within reason), the more humanizing the effect. But there's a threshold. Mistakes that call into question your core competence or moral character will destroy credibility, not enhance it. A CEO who fumbles their microphone is relatable. A CEO who fumbles the company's financial statements is unemployed.

Context determines whether the pratfall effect activates or backfires. In low-stakes social situations, small mistakes consistently boost appeal. But in high-stakes professional contexts, the same errors can be devastating. A surgeon who drops their coffee in the break room becomes more approachable. A surgeon who trembles during a procedure loses patients. The difference lies in whether the mistake is relevant to the domain of competence.

Cultural factors also modulate the effect. Research indicates the pratfall effect is stronger in individualist Western cultures than in collectivist Eastern cultures. In societies that emphasize group harmony and social roles, individual displays of fallibility may be interpreted differently. What reads as "authentic" in Silicon Valley might read as "unprofessional" in Tokyo or Seoul.

"When the competent person made a mistake, they became more likable. When the less competent person made the same mistake, their likability decreased."

- Elliot Aronson, 1966 Pratfall Effect Study

Cognitive load introduces another boundary condition. Marketing research has uncovered something fascinating: the pratfall effect can actually reverse when people are thinking carefully and analytically. In one experiment, consumers in low-effort decision contexts doubled their purchase rates when shown a product with a minor flaw (like a broken chocolate piece). But when the same consumers were in high-effort contexts, the flaw cut purchase rates in half. This suggests that the effect operates through intuitive, emotional processing rather than deliberate analysis.

The pratfall effect has migrated from psychology labs into corporate boardrooms, marketing campaigns, and leadership development programs. Its applications are as varied as human social interaction itself.

In marketing, some of the most memorable campaigns have weaponized imperfection. Volkswagen's famous "Lemon" advertisement in the 1960s featured a Beetle that failed inspection, turning a quality control reject into proof of rigorous standards. Domino's Pizza ran a brutally honest campaign in 2009 admitting their crust "tasted like cardboard" before reformulating it. Sales increased 14% in the following quarter. These campaigns worked because the companies had already established product competence. The admission of flaws signaled honesty, not incompetence.

In leadership contexts, the strategic deployment of vulnerability has become almost an art form. Modern leadership theory increasingly emphasizes authentic leadership over the old command-and-control model. Leaders who share their mistakes and uncertainties create psychological safety for their teams. But there's a fine line. A leader who constantly apologizes or shows too much uncertainty erodes confidence. The pratfall effect works for leaders who have clearly demonstrated competence first.

Research on charismatic leadership shows that followers rate leaders more favorably when they occasionally show human flaws, provided those flaws are minor and unrelated to their leadership capabilities. A CEO who mentions dyslexia becomes more relatable. A CEO who can't read financial reports becomes unemployable.

In personal branding, particularly on social media, the pratfall effect manifests in what's sometimes called "curated authenticity." People share carefully selected imperfections to seem more genuine. But here's the trap: if the vulnerability feels manufactured or strategic, it backfires completely. Audiences are remarkably good at detecting performative authenticity. The effect only works when the mistake is genuinely inadvertent or the vulnerability is truly felt.

The widespread knowledge of the pratfall effect has created a perverse incentive: people trying to manufacture mistakes to seem more likable. This almost never works. The research is clear that authenticity is crucial. When people sense that you're strategically deploying vulnerability, it reads as manipulation, not openness.

Social media has accelerated this trend. Influencers post "perfectly imperfect" photos with captions about their struggles, carefully crafted to seem spontaneous. Corporate leaders schedule "unscripted" moments in presentations. The problem is that authentic pratfalls are, by definition, unplanned. When you plan to spill your coffee, it's not a pratfall anymore. It's theater.

Conscious attempts to use the pratfall effect often backfire. Audiences can detect manufactured vulnerability with surprising accuracy.

This creates a paradox: the more you know about the pratfall effect, the harder it becomes to benefit from it naturally. Conscious attempts to leverage it often come across as inauthentic. The sweet spot is developing enough self-acceptance that you don't reflexively hide or overcompensate for small mistakes. Let them happen. Acknowledge them lightly. Move on.

Research on impression management shows that people are sophisticated detectors of self-presentational strategies. We evolved in small groups where knowing who to trust was literally life or death. That machinery is still running, and it's remarkably good at spotting performance. The best advice might be: don't try to use the pratfall effect. Just stop trying so hard to be perfect.

The pratfall effect doesn't operate equally for everyone. A 1972 study by Kay Deaux found that male observers were more influenced by the effect than female observers. This gender difference hasn't been consistently replicated in subsequent research, but it raises important questions about how social roles and expectations moderate psychological phenomena.

More robust is the finding that the effect depends critically on the observer's self-esteem and the perceived similarity between observer and target. People with average self-esteem show the strongest pratfall effect. They're threatened by extreme competence but reassured by humanizing mistakes. People with very high self-esteem aren't threatened by others' competence in the first place, so they show less increase in liking after a pratfall. People with very low self-esteem may actually increase their liking for perfect performers, using them as aspirational figures.

Status and power dynamics complicate the picture further. When someone higher in a hierarchy makes a mistake, it can reduce perceived distance and make them more approachable. When someone lower in a hierarchy makes a mistake, it can confirm existing stereotypes about their competence. This asymmetry means the pratfall effect may actually reinforce existing status structures rather than flatten them.

"A minor mistake makes them feel more approachable and relatable, fostering social connection."

- Explore Psychology, on the humanizing mechanism

Research on workplace dynamics shows that women and minorities often face what's called a narrower "band of acceptable behavior" than their male or majority-group counterparts. A mistake that humanizes a white male executive might be seen as evidence of incompetence in a female executive or executive of color. The pratfall effect assumes a base level of perceived competence that not everyone is granted equally.

So what do we do with this knowledge? The research points to several practical insights that apply whether you're leading a company, building a personal brand, or just trying to connect with other humans.

First, establish competence before showing vulnerability. The pratfall effect is not an alternative to being good at what you do. It's an amplifier that only works after you've demonstrated capability. If you're new to a job, a team, or a social circle, focus on proving your value first. Once you've established that foundation, small mistakes will humanize you rather than undermine you.

Second, let mistakes happen naturally rather than engineering them. The research consistently shows that authenticity is key. You can't strategically deploy the pratfall effect without it becoming obvious manipulation. What you can do is develop enough self-acceptance that you don't catastrophize or hide minor errors. Acknowledge them lightly. Maybe make a brief self-deprecating comment. Then move on. The confidence to be imperfect is itself attractive.

Third, match your vulnerability to the context. High-stakes situations call for reliable competence. Save the humanizing moments for lower-stakes interactions. A coffee spill before a presentation is fine. A mental blank during the presentation is not. Understanding this boundary is crucial.

Fourth, be aware of the structural inequalities in how mistakes are perceived. If you're in a demographic group that already faces credibility questions, you may not have the luxury of letting mistakes humanize you. This is unfair, but it's real. The pratfall effect assumes a baseline of assumed competence that's not equally distributed. Acknowledging this reality is important for both those navigating it and those working to change it.

Fifth, use the principle to build psychological safety in teams. As a leader or team member, sharing your own minor struggles and mistakes can create an environment where others feel safe doing the same. This is where the pratfall effect becomes truly valuable, not as a personal branding tool, but as a relationship-building mechanism. When everyone feels they can be imperfect without judgment, creativity and risk-taking flourish.

As AI handles tasks requiring perfect accuracy, the human capacity for authentic connection through strategic imperfection becomes more valuable, not less.

The deeper lesson of the pratfall effect is that perfection is often the enemy of connection. We're drawn to people we can relate to, and flawlessness creates distance. The most effective leaders, the most trusted colleagues, and the most engaging public figures are those who've mastered what might be called "confident imperfection." They're clearly capable, but they don't pretend to be infallible.

As artificial intelligence and automation handle more tasks that require perfect accuracy, this human capacity for strategic imperfection may become more valuable, not less. The ability to connect authentically, to signal trustworthiness through vulnerability, to create psychological safety through admitted fallibility - these are deeply human skills that machines won't replicate anytime soon.

The pratfall effect reminds us that we're wired for connection, not perfection. Our social brains evolved to navigate complex webs of relationships, not to admire flawless performers from a distance. When someone we respect shows us they're human too, something in us relaxes. We move from evaluation mode to connection mode. And in that shift, something genuinely valuable happens: we remember that competence and humanity aren't opposites. They're partners.

The next time you make a small mistake in front of someone, you might consider it not as a failure to hide, but as an opportunity for connection. Not because you're trying to manipulate how they see you, but because you're giving them permission to see the real you. And research suggests that's exactly what they've been waiting for all along.

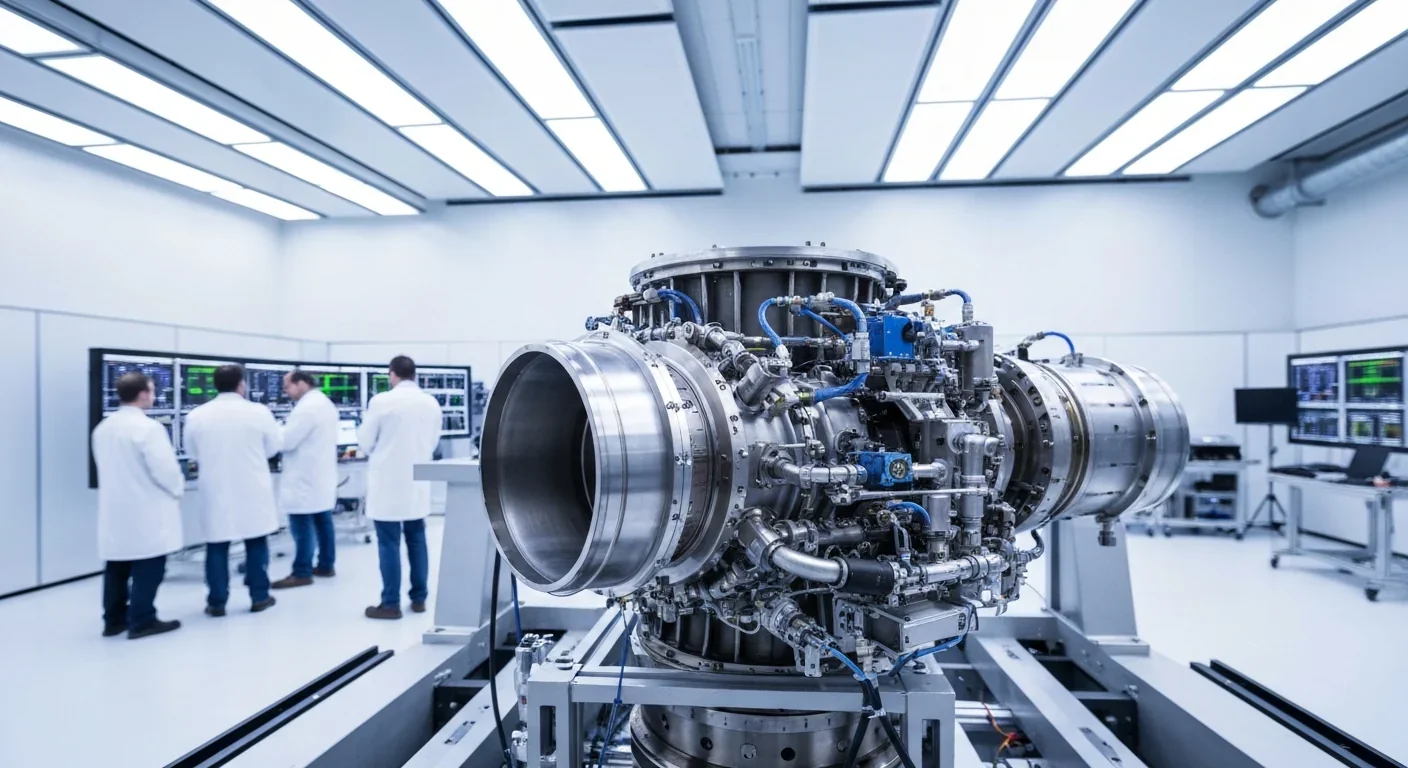

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

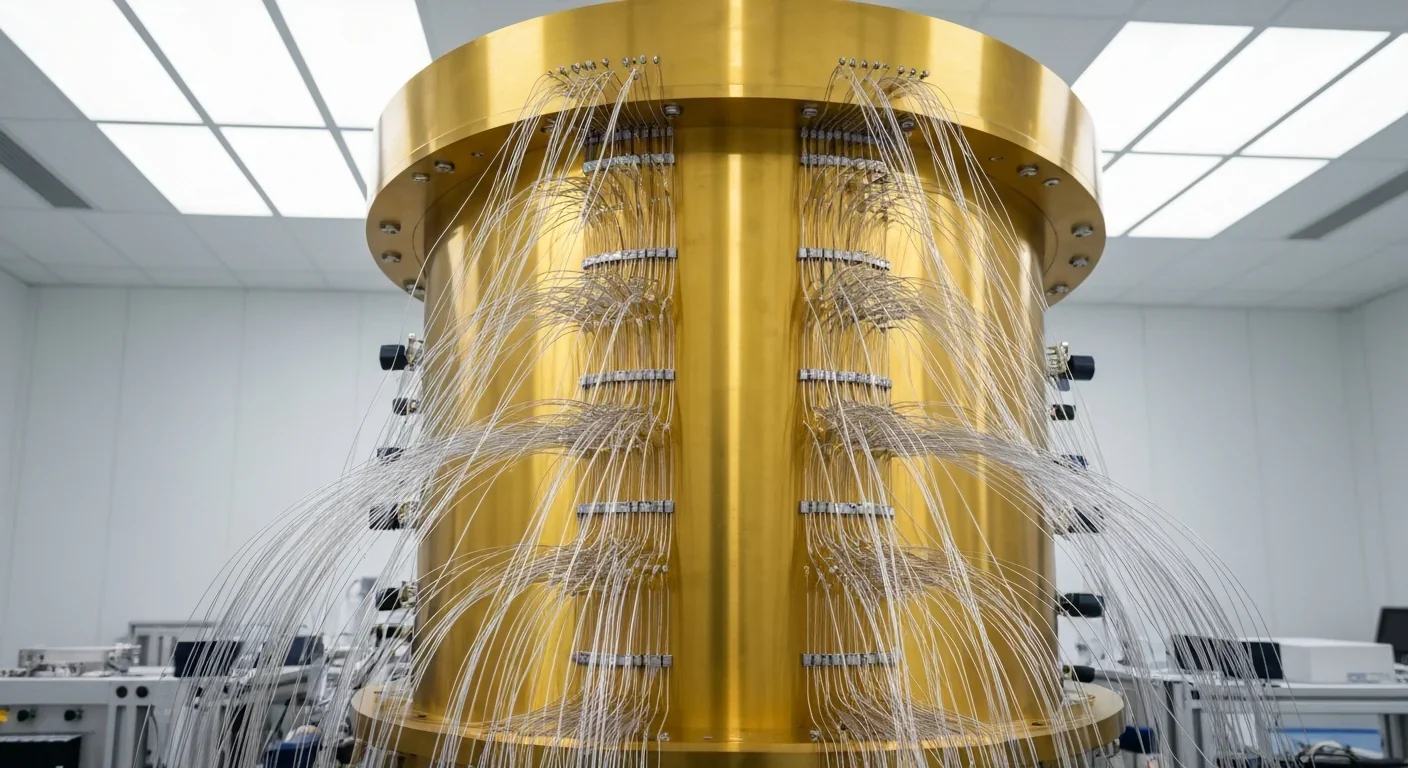

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.