The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The doorway effect - forgetting why you entered a room - is a real cognitive phenomenon caused by your brain's automatic event segmentation system. Research shows doorways trigger memory boundaries, especially under cognitive load, but simple strategies like rehearsing your goal can help you remember.

You're watching TV when you suddenly crave popcorn. You get up, walk to the kitchen, pass through the doorway, and... wait, what did you want? You stand there, completely blank, staring at the refrigerator like it holds the answer to a riddle you've already forgotten.

This isn't absent-mindedness. It's not early-onset dementia. It's a well-documented cognitive phenomenon called the doorway effect, and it happens because your brain is doing exactly what evolution designed it to do: organizing your experiences into manageable chunks.

For years, researchers dismissed this experience as anecdotal quirk. But when cognitive scientists at the University of Notre Dame started testing it systematically, they discovered something remarkable: doorways actually do cause forgetting, and the effect is so consistent across studies that it now has an official name.

Dr. Jessica McFadyen and Dr. Oliver Baumann at the University of Queensland conducted virtual reality experiments to understand exactly when and why this happens. In their first test, 29 participants wore VR headsets and moved through different rooms while trying to remember objects. Surprisingly, doorways had no effect on memory.

But when they repeated the experiment with a twist - asking 45 people to perform a difficult counting task while memorizing objects - the doorway effect appeared. Participants who crossed through doorways were significantly more likely to misidentify objects, especially when their attention was divided.

The key isn't the doorway itself - it's what the doorway represents to your brain as a signal that one event has ended and another has begun.

Every moment of your life is continuous - a seamless flow of sensations, thoughts, and actions. Yet when you remember your day, you don't recall an undifferentiated stream. You remember breakfast, the commute, that awkward meeting, lunch with Sarah. Your brain has automatically segmented your experience into discrete events.

This process is called event segmentation, and it's fundamental to how human memory works. According to event segmentation theory, your brain constantly monitors your environment for changes and uses those changes to create boundaries between events.

When you encounter a significant change - a new location, a shift in activity, or the introduction of new people - your brain interprets this as the end of one event and the beginning of another. At that boundary, your neural patterns literally reconfigure.

Recent fMRI research has revealed the precise choreography of this mental reset. About 12 seconds before you consciously register an event boundary, activity begins in your anterior temporal regions. Around 4 seconds before, your parietal and dorsal attention networks kick in. Then, roughly 12 seconds after you cross the boundary, your entire brain stabilizes into a new pattern.

Doorways are powerful event boundaries because they combine multiple cues: a visual change (new room), a spatial shift (different location), and often a goal transition (you went to the kitchen to get something, not to continue what you were doing in the living room). Your brain sees all these signals and concludes: "New event. Time to update the mental model."

Not all boundaries are created equal. You might shift your attention from reading to checking your phone without forgetting what you were thinking about. So why are doorways so effective at wiping your mental slate?

Spatial context is uniquely powerful in memory. Your hippocampus - the brain region critical for forming new memories - contains specialized neurons called place cells that fire when you're in specific locations. It also has time cells that activate at particular moments in a sequence of events.

When you move through a doorway into a new room, you're not just changing your physical position. You're entering a completely different spatial context, which triggers your hippocampus to update its internal map. This spatial updating process can interfere with your ability to maintain active goals in working memory.

"Event segmentation is an ongoing, automatic process that happens without conscious control as your brain continuously monitors for changes and adjusts its models of reality."

- Cognitive Neuroscience Research

Think of working memory as your brain's mental workspace - the small scratch pad where you hold information you're currently using. Working memory has limited capacity, typically around 3-7 items. When you cross a threshold into a new environment, your brain needs to load new spatial information: where's the light switch, where are the obstacles, what's the layout?

If your attention is already stretched thin - say, you're also mentally composing an email or replaying a conversation - there's not enough cognitive bandwidth to maintain everything. The oldest, least-reinforced information gets pushed out. And if you only thought about popcorn once before you stood up, that intention is the first casualty.

The doorway effect isn't a fixed phenomenon. It strengthens and weakens based on several factors, and understanding these can help you recognize when you're most vulnerable.

Cognitive load matters enormously. When McFadyen and Baumann added a counting task to their VR experiment, the doorway effect appeared. Without that extra mental burden, participants remembered just fine. This explains why you're more likely to forget your intention when you're stressed, tired, or juggling multiple thoughts.

Context change amplifies the effect. When the rooms in the VR study were visually identical, doorways had no effect on memory. The brain apparently weights the boundary signal against the degree of environmental change. A doorway between two nearly identical rooms doesn't register as a strong event boundary. But a doorway from your cozy living room to your bright, tile-floored kitchen? That's a clear signal to reset.

Individual differences exist. Some people experience the doorway effect more than others. While the research hasn't fully mapped out all the variables, working memory capacity likely plays a role. If you have a smaller working memory capacity, you'll be more susceptible to interruption when new information (like spatial context) demands attention.

Age might matter too, though not in the way you'd expect. Older adults often show different patterns of event segmentation compared to younger adults, but this doesn't necessarily mean more forgetting - sometimes it means they segment events at different points or use different cues.

The neuroscience of event boundaries has come into sharper focus in recent years. When researchers scan people's brains while they watch movies or navigate spaces, they see increased activity in frontal and posterior brain regions just before participants identify an event boundary.

Two distinct neural mechanisms appear to govern boundary detection: prediction error and prediction uncertainty. Prediction error occurs when something unexpected happens - you thought the room would be dark, but the light is on. Prediction uncertainty happens when you simply can't predict what's coming next - you've never been in this room before.

Different brain networks handle these two types of boundaries. Error-driven boundaries engage your ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior temporal areas. Uncertainty-driven boundaries activate your dorsal attention and visual networks. But both lead to the same outcome: your brain updates its model of what's happening, and in the process, weakly-held information can slip away.

Your brain doesn't wait until you're through the doorway to start the reset - it begins reorganizing neural patterns about 12 seconds before you cross the threshold and stabilizes into a new configuration roughly 12 seconds after.

The temporal dynamics are fascinating. Your brain doesn't wait until you're through the doorway to start the reset. It begins reorganizing neural patterns before you cross the threshold, continues during the transition, and then stabilizes into a new configuration about 12 seconds after the boundary. That's why you might feel the "what did I come here for?" confusion hit you a moment after you've entered the room, not instantly at the threshold.

Virtual reality experiments are controlled and replicable, but do these findings hold up in messy, real-world environments? The answer is yes, with some interesting nuances.

Gabriel Radvansky, whose lab at Notre Dame pioneered doorway effect research, conducted studies where participants physically walked through actual doorways while carrying objects and remembering tasks. The effect persisted. Crossing a doorway in a real building produced the same memory impairment as crossing one in VR.

But the effect isn't limited to physical doorways. Radvansky also found that virtual boundaries - moving from one computer desktop to another, switching between applications, or even transitioning between different websites - can produce similar effects. What matters is the perceptual and cognitive signal that you've moved from one context to another.

Open office environments might actually reduce some doorway effects because they lack strong spatial boundaries. But they introduce other problems: without clear event boundaries, people can struggle to mentally separate tasks, leading to a sense of cognitive overload. The brain seems to benefit from boundaries - they help organize memory - but they come with the trade-off of increased forgetting at the transition points.

It's tempting to view the doorway effect as a frustrating glitch in human cognition. But from an evolutionary perspective, event segmentation is incredibly useful.

Imagine you're a hunter-gatherer moving from the safety of your cave into the dangerous savanna. Your brain needs to rapidly switch contexts: from rest mode to high-alert mode, from social cognition to predator detection, from one set of spatial landmarks to an entirely different landscape. Event segmentation allows your brain to efficiently package old information and make room for new, immediately relevant data.

If you kept every detail in active memory across context changes, you'd quickly overload. Your brain would waste resources maintaining information that's no longer relevant (the conversation you just had) while trying to process new demands (where's the watering hole, where's the lion). The doorway effect is your brain being efficiently selective, prioritizing current context over previous intentions.

The problem in modern life is that we frequently move between spaces for trivial reasons, and we expect to seamlessly maintain goals across these transitions. We've built environments full of rooms and doorways, but our brains are still using Stone Age algorithms optimized for less frequent, more meaningful context shifts.

One crucial insight from doorway effect research is that memory is not a single system. The effect appears to primarily impact working memory - your ability to actively hold and manipulate information. It doesn't erase long-term memory of facts or past events.

Different types of memory tests reveal different patterns. When researchers test recall - asking people to retrieve information from memory without cues - the doorway effect is strong. But when they test recognition - showing people options and asking if they've seen them before - the effect often disappears or weakens considerably.

"If we want to escape the enchantment of the doorway, our best chance is to keep a focused mind. Keep thinking about popcorn the next time you want to get some to eat while watching your favourite TV show."

- Dr. Jessica McFadyen and Dr. Oliver Baumann, University of Queensland

This distinction matters. The doorway effect doesn't mean you've truly forgotten why you entered the room in any permanent sense. The information is still in your brain; it's just temporarily less accessible. With the right cue, you can often retrieve it. That's why retracing your steps back to the original room frequently works - you're reinstating the spatial context that encoded the memory.

Understanding the science behind the doorway effect points to several evidence-based strategies for maintaining your intentions when moving between rooms.

Keep rehearsing your goal. The researchers' number one recommendation is to keep your intention active in working memory by repeating it as you move. "Popcorn, popcorn, popcorn" as you walk from the living room to the kitchen. It feels silly, but it works because you're continuously refreshing the information, preventing it from being displaced.

Reduce cognitive load. Don't try to solve complex problems while in transit between rooms. If you're mentally composing an email or running through your to-do list as you walk, you're increasing the chance that your original intention will be pushed out of working memory. Save the mental multitasking for when you're stationary.

Create stronger encoding. Before you stand up, pause for a moment and really think about what you're going to do and why. "I'm going to the kitchen to get popcorn because I'm hungry and I want a snack while watching this show." The richer the encoding - the more details and connections you create - the more resistant the memory is to disruption.

Use physical cues. Take something with you that reminds you of your goal. If you're going to the bedroom to get your phone charger, take your dead phone with you. The physical object serves as a persistent reminder that bypasses working memory entirely.

Retrace your steps. If you do forget, go back to where you had the thought. Reinstating the original spatial context often brings back the memory because spatial context is deeply intertwined with memory encoding. This isn't just folk wisdom; it's supported by research on context-dependent memory.

Minimize unnecessary transitions. If you're working on a complex task, try to gather everything you need before you start so you don't have to keep crossing thresholds. Each doorway crossing is a potential memory disruption point.

Embrace external memory. For important tasks, don't rely solely on your brain. Use notes, phone reminders, or even just carry a small notebook. Our brains evolved to remember things differently than modern life demands; there's no shame in using tools to bridge that gap.

The doorway effect is more than a curious quirk - it's a window into fundamental principles of how human memory works.

It demonstrates that memory is not a passive recording device but an active, context-sensitive system. Your brain doesn't store experiences like files on a hard drive; it encodes them relative to situations, locations, and mental states. The same piece of information can be easy to remember in one context and difficult to retrieve in another.

It shows that attention and memory are inextricably linked. You can't remember what you weren't paying attention to, and divided attention at a critical moment - like crossing a threshold - can cause even recently-formed intentions to vanish.

It reveals that your brain is constantly predicting and updating. Event segmentation happens automatically, without conscious control, as your brain continuously monitors for changes and adjusts its models of reality. You don't decide to create event boundaries; they emerge from the brain's built-in pattern detection systems.

And perhaps most importantly, it illustrates that human cognition represents trade-offs, not perfection. Evolution didn't design your brain to be flawless at everything; it designed your brain to be good enough at the things that mattered for survival and reproduction in ancestral environments. The doorway effect is a side effect of a memory system optimized for different challenges than remembering to grab batteries while you're in the garage.

As cognitive neuroscience advances, phenomena like the doorway effect are helping researchers build more sophisticated models of how memory, attention, and context interact. This has practical implications beyond explaining why you forgot the popcorn.

Understanding event segmentation could improve educational strategies. If students segment information into events based on spatial or temporal cues, structuring learning environments and materials to create optimal event boundaries might enhance retention.

It could inform the design of digital interfaces. If switching between apps or browser tabs creates event boundaries that impair working memory, designers could build features that help users maintain context across transitions - perhaps by preserving visual continuity or providing memory cues.

The doorway effect is a reminder that you are not a computer - your memory works through dynamic, context-dependent reconstruction, not perfect storage and retrieval.

It might even help people with memory impairments. If we understand precisely when and why memory fails at boundaries, we could develop targeted interventions for people with conditions like ADHD or early Alzheimer's disease.

The next time you walk into a room and forget why you're there, don't beat yourself up. Your brain isn't broken. It's doing exactly what millions of years of evolution shaped it to do: efficiently organizing your continuous experience into discrete, meaningful events.

The doorway effect is a reminder that you are not a computer. Your memory doesn't work through perfect storage and retrieval; it works through dynamic, context-dependent reconstruction. Understanding this won't eliminate those frustrating moments of forgetfulness, but it might help you appreciate the remarkable cognitive machinery that produces them.

And if you really want to remember to get that popcorn? Just keep thinking about it as you walk. Your brain will thank you.

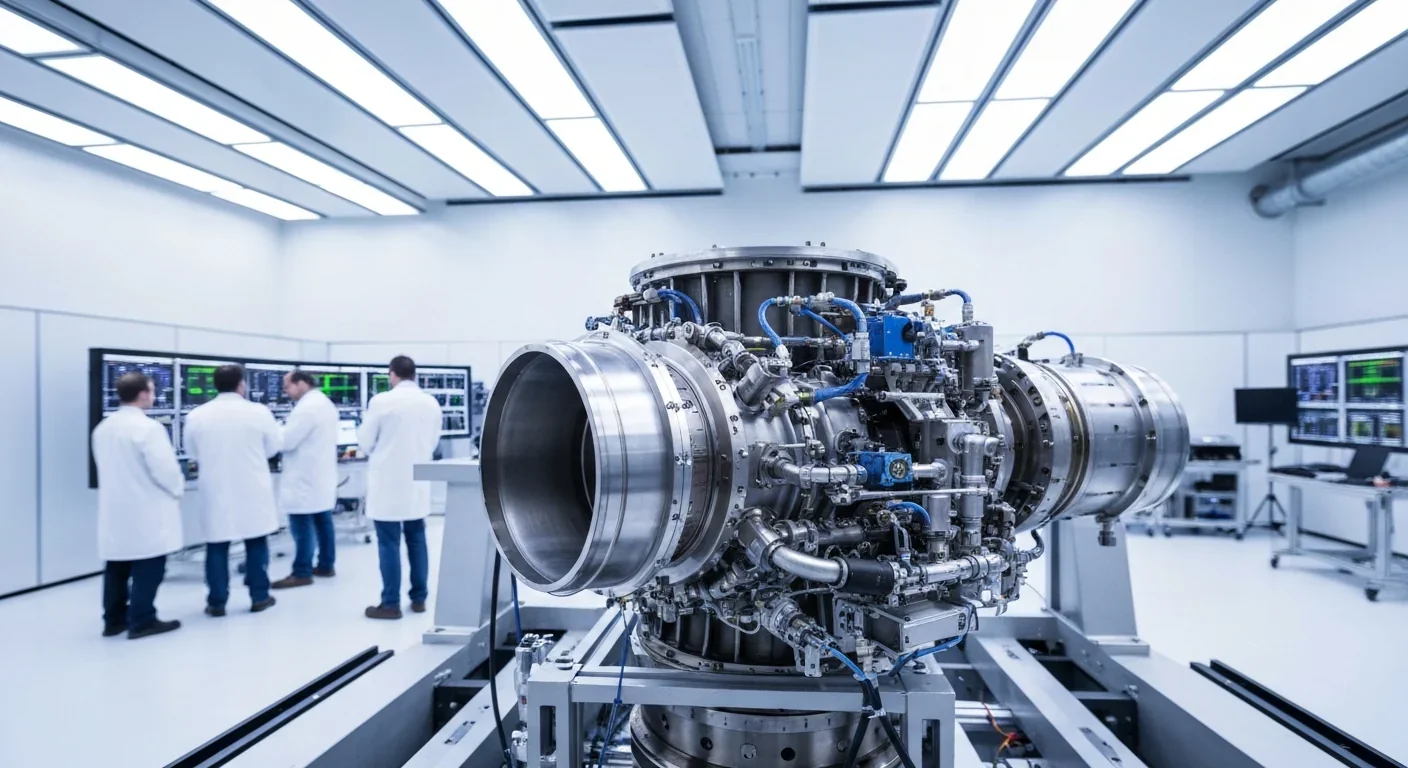

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

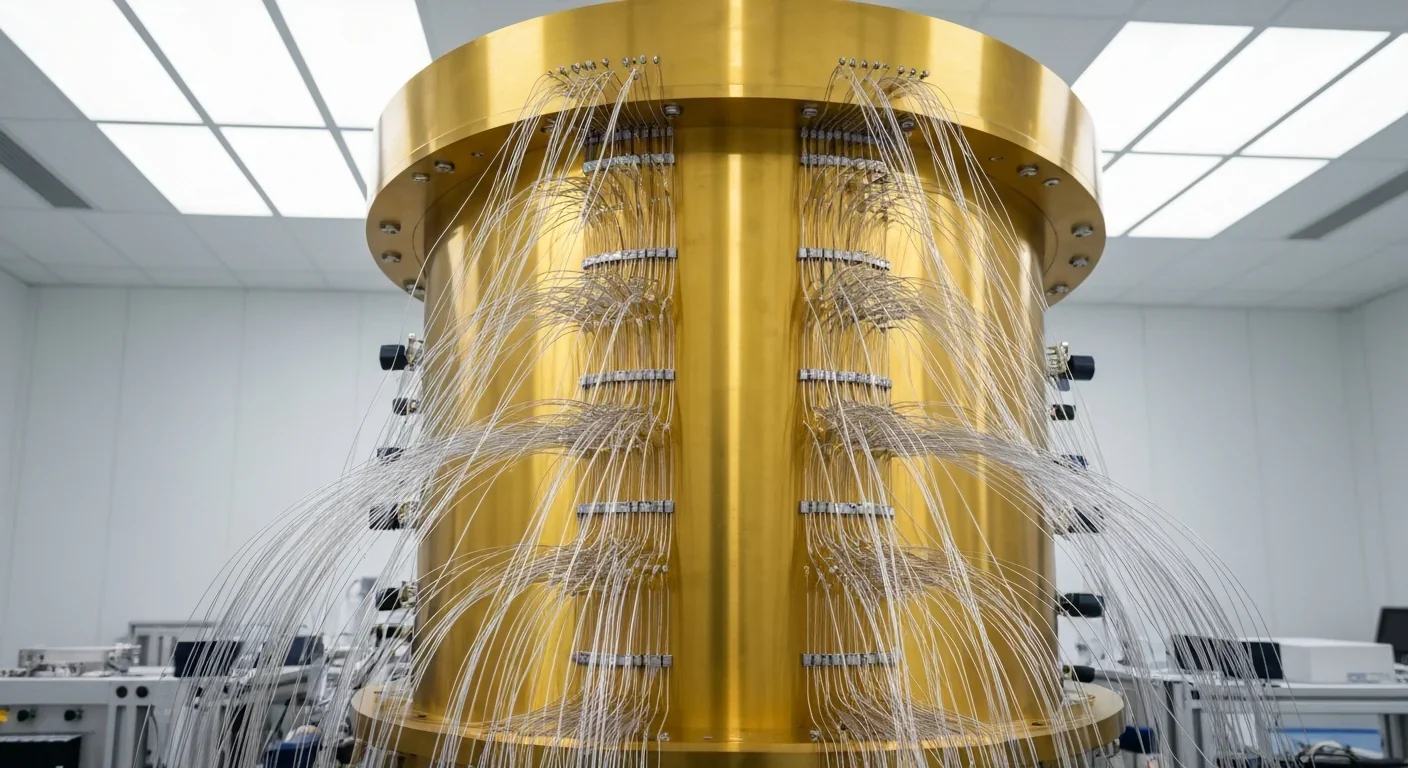

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.