Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Neuroscience reveals the cross-race effect - our difficulty recognizing faces from other ethnic groups - stems from neural processing differences that occur within 600 milliseconds. This bias contributes to 42% of wrongful convictions but can be reduced through deliberate training and diverse social exposure.

Your brain makes a crucial decision about every face you encounter within 600 milliseconds of first glance. That split-second judgment, happening far below conscious awareness, shapes everything from your social interactions to your testimony in a courtroom. It's called the cross-race effect, and it's reshaping how we think about bias, justice, and the very mechanics of human perception.

Scientists have long documented this phenomenon: people recognize and remember faces from their own racial group far better than those from other groups. What's new is our understanding of why it happens - and more importantly, what we might be able to do about it. Recent neuroscience research using AI-powered brain imaging reveals that this isn't just a matter of exposure or social conditioning. The bias is literally encoded in how our neural circuitry processes facial features, creating systematic perceptual distortions that manifest in milliseconds.

The implications ripple through society in ways most of us never consider. Eyewitness misidentification contributes to roughly half of all wrongful convictions, with cross-race identification errors playing an outsized role. A witness asked to identify someone of a different race is more than 50% more likely to make a mistake. In one study of 271 real court cases, correct identification rates dropped from 60% for same-race suspects to just 45% for other-race suspects.

But this isn't a story about inevitable bias. It's about understanding the machinery well enough to fix it.

Inside your skull, a region called the fusiform face area acts as your brain's facial recognition specialist. When you look at faces from your own racial group, this area lights up with detailed, distinctive neural patterns. Each face generates a unique signature - a rich tapestry of activation that helps you distinguish between individuals.

Other-race faces tell a different story. When researchers at the University of Toronto used EEG to measure brain activity while people viewed faces, they found something striking: neural responses to other-race faces were flatter, less distinct, more generic. Instead of processing each face as a unique individual, the brain treats them more like interchangeable members of a category.

"The bias in face recognition isn't just a result of social conditioning or lack of exposure - it is rooted in how our brain constructs and differentiates facial features at an unconscious level, within milliseconds of visual contact."

- Adrian Nestor, University of Toronto Scarborough

Using generative adversarial networks (GANs), Nestor's team reconstructed what participants were actually seeing when they looked at faces. The results were revealing: other-race faces appeared more average, younger, and more emotionally expressive than they actually were. The brain wasn't just failing to encode details - it was actively creating a distorted representation.

This processing difference involves a specific brain wave called the N170 component, which fires about 170 milliseconds after seeing a face. For own-race faces, this component shows strong, differentiated responses. For other-race faces, the amplitude drops, signaling reduced perceptual processing.

The amygdala adds another layer of complexity. This almond-shaped structure, central to processing emotion and threat, shows heightened activation when viewing other-race faces. Robert Sapolsky, a behavioral scientist at Stanford, notes that the amygdala "is the most quickly reacting part of our brain; a 150-millisecond exposure can trigger fight or flight responses."

The brain's initial bias response happens in milliseconds, but higher-order regions like the anterior cingulate cortex can modulate this automatic reaction when we consciously process faces as individuals rather than categories.

But here's where it gets interesting: the amygdala's initial response can be modulated by other brain regions, particularly the anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. When people consciously process faces - when they're motivated to see individuals rather than categories - these higher-order regions can dampen the automatic bias response.

If you're wondering whether this bias is hardwired from birth, the answer is nuanced. Infants as young as three months show early signs of the cross-race effect, preferring to look at faces that match the racial characteristics of their primary caregivers. But the effect isn't set in stone - it's more like a developmental window that opens and then, without the right input, begins to close.

Research on infant face recognition shows a critical period between three and nine months. During this window, babies are remarkably flexible in their facial recognition abilities, capable of distinguishing individuals across racial groups with equal facility. But as they approach their first birthday, their perceptual systems begin to specialize, tuning into the statistical regularities of the faces they see most often.

By ages three to four, children begin showing clear in-group preferences in how they allocate resources and attention. A 2020 study found that White children who had developed "racial constancy" - the understanding that race is a stable, unchanging characteristic - were significantly more likely to share equally with White peers than with Black peers. Children who hadn't yet developed this concept showed no such bias.

What's particularly striking is that this isn't about explicit prejudice. Young children aren't making conscious decisions to discriminate. Instead, they're responding to the perceptual categories their developing brains have learned to emphasize. The bias emerges from pattern recognition, not malice.

This developmental timeline suggests a potential intervention point. If the critical window for facial recognition expertise extends through early childhood, then diverse social environments during these years might prevent the bias from taking root. Research bears this out: children raised in racially diverse communities show reduced cross-race effects compared to those in more homogeneous environments.

The real-world consequences of this perceptual bias become starkest in courtrooms. According to the Innocence Project, eyewitness misidentification contributed to approximately 42% of wrongful convictions that were later overturned by DNA evidence. Cross-racial misidentification was a factor in many of these cases.

Consider the case of Otis Boone, convicted in 2011 based on the testimony of two White witnesses who identified him from a lineup. The victims had limited exposure to their attacker, and the lineup procedures failed to account for cross-race identification challenges. Boone spent seven years in prison before his conviction was overturned in 2018.

Or Don Ray Adams, identified by a witness in 1990 and later exonerated after the witness recanted her testimony, acknowledging that the stress of the situation and racial differences had compromised her memory.

The problem compounds when other factors come into play. The "weapon focus effect" causes witnesses to concentrate on threatening objects rather than faces, further degrading memory. A 2016 study found that witnesses "overwhelmingly remembered Black suspects' faces incorrectly when they witnessed crimes that are more often associated with Black males, such as drive-by shootings." The interaction of stereotypes with perceptual bias creates a perfect storm for misidentification.

"Eyewitness misidentification has contributed to one in five wrongful death penalty convictions. Misidentifications are especially likely when the witness and suspect are of different races."

- ACLU Report, Fatal Flaws

Even the way police conduct interviews can exacerbate the problem. Leading questions - especially those using vivid language - can implant false memories. A classic 1974 study showed that asking witnesses whether they saw broken glass when cars "smashed" versus "hit" significantly altered their recollection, with the more dramatic verb causing people to report seeing glass that wasn't there.

According to ACLU research, "eyewitness misidentification has contributed to one in five wrongful death penalty convictions. Misidentifications are especially likely when the witness and suspect are of different races." When the stakes are literally life and death, the cross-race effect's impact becomes impossible to ignore.

Not everyone experiences the cross-race effect equally. Variation in exposure explains much of the difference. People who live and work in racially diverse environments show reduced bias compared to those in homogeneous communities. Interestingly, the effect is largely symmetric - members of minority groups show similar deficits in recognizing majority-group faces, though with some variations based on media exposure and social dynamics.

Studies of passport officers and other professionals who regularly encounter faces from diverse backgrounds show reduced but not eliminated cross-race effects. Years of practice narrows the gap, but doesn't close it completely. This suggests that while perceptual expertise can be developed, it requires sustained, meaningful engagement rather than passive exposure.

Cultural context matters too. Research across different countries reveals that the strength of the cross-race effect varies with the degree of racial integration and intergroup contact in a society. In more segregated societies, the effect tends to be more pronounced. In multicultural urban centers with high rates of cross-racial interaction, it diminishes.

Individual differences in social cognition also play a role. People with higher levels of empathy and those who score lower on measures of implicit bias show somewhat reduced cross-race effects, suggesting that motivation and cognitive strategies can partially compensate for perceptual limitations.

The age at which someone first has significant contact with other racial groups makes a difference too. Those who grow up in diverse environments from infancy show the smallest effects. Those who don't encounter diversity until adulthood show the largest. This points again to those critical developmental windows when the brain is most plastic and capable of learning to distinguish faces across racial categories.

For decades, psychologists have promoted the "contact hypothesis" - the idea that meaningful interaction with members of other racial groups would reduce prejudice and, presumably, perceptual bias. The evidence is mixed.

Contact does help, but not all contact is created equal. Superficial interactions - passing people on the street, seeing faces in media - don't seem to make much difference. What matters is sustained, individuated contact where you learn to see people as distinct individuals rather than representatives of a category.

Studies show that when participants are explicitly forewarned about the cross-race effect and motivated to overcome it, identification accuracy improves. Training programs that emphasize individuation - deliberately noting distinctive features and actively processing faces at a detailed level - can reduce the effect by 10-20%.

Training reduces the cross-race effect temporarily, but improvements fade without continued practice. Real-life immersion in diverse environments produces more lasting changes, though even extensive exposure rarely eliminates the bias completely.

But there's a catch: these improvements tend to fade unless reinforced through continued practice. One-time training sessions show initial promise, then performance regresses toward baseline. Real-life immersion in diverse environments produces more durable improvements, but they still don't completely eliminate the bias.

Virtual reality offers an intriguing possibility. Nestor's research suggests that "immersive virtual-reality exposure" might effectively rewire neural pathways by providing controlled, intensive practice in recognizing diverse faces. Unlike real-world exposure, VR could systematically vary facial features to train the perceptual system more efficiently.

Machine learning algorithms face similar challenges. Early facial recognition systems, trained predominantly on White faces, performed poorly on other racial groups. More diverse training datasets have improved performance, but disparities remain - a reminder that both biological and artificial neural networks require diverse input to develop unbiased recognition.

The accumulating evidence has prompted reforms in how law enforcement handles eyewitness identification. The National Institute of Justice has published guidelines calling for double-blind lineups (where the officer administering the lineup doesn't know which person is the suspect), sequential rather than simultaneous presentation of lineup members, and clear instructions to witnesses that the perpetrator may not be present.

Some jurisdictions now allow expert testimony on eyewitness identification, including the cross-race effect. This helps juries understand the limitations of eyewitness memory and weigh testimony appropriately. The Innocence Project has pushed for these reforms based on the overwhelming evidence that misidentification is a leading cause of wrongful convictions.

Courts are also becoming more receptive to challenges based on cross-race identification issues. Defense attorneys increasingly cite the scientific literature on the cross-race effect when questioning the reliability of identification evidence, particularly in cases where identification is the primary evidence.

But implementation remains uneven. Many law enforcement agencies have adopted the guidelines in theory while failing to implement them consistently in practice. Real-world cases continue to show persistent bias, indicating that "compliance may be superficial" and that cultural change within police departments lags behind policy updates.

Training for law enforcement on the cross-race effect is becoming more common, though its effectiveness depends on implementation. Simple awareness of the bias helps somewhat, but structured training that includes practice in individuated face processing shows better results.

So what does this mean for individuals trying to overcome their own perceptual limitations? The research points to several practical strategies.

First, conscious processing matters. When you meet someone from a different racial background, deliberately note distinctive features - the specific shape of their eyes, the contours of their face, unique characteristics that distinguish them as an individual. This moves processing from categorical (other-race face) to individuated (this particular person).

Second, seek diverse social environments. If your workplace, neighborhood, and social circles are homogeneous, you're reinforcing perceptual biases through lack of practice. Deliberate exposure to diverse faces - through social interactions, not just media consumption - provides your perceptual system with the training data it needs.

Third, check your confidence. People consistently overestimate their ability to recognize other-race faces. Research shows that confidence and accuracy are poorly correlated in cross-race identifications. If you're called to identify someone of a different race, acknowledge the limitation rather than assuming your memory is reliable.

The cross-race effect is a perceptual limitation, not a moral failing. Recognizing this bias creates an opportunity to compensate through deliberate strategies and procedural safeguards.

Fourth, advocate for systemic changes. If you're in a position to influence organizational practices - whether in law enforcement, hiring, or any context where accurate identification matters - push for procedures that account for perceptual biases. This might mean double-blind procedures, multiple independent verifications, or expert consultation.

Fifth, recognize that this is a perceptual, not moral, failing. The cross-race effect doesn't make you a bad person - it makes you a human with a visual system shaped by your developmental environment. But recognizing the bias creates an opportunity to compensate for it through deliberate strategies.

Understanding the cross-race effect reveals something profound about human cognition: our perceptual systems are not neutral recording devices. They're prediction machines, constantly making bets about what's important to encode based on past experience. When our environments lack diversity, our brains optimize for the patterns they encounter most often, creating systematic blind spots.

The encouraging news is that these systems remain plastic throughout life, capable of relearning and adapting. The challenging news is that changing them requires more than passive exposure - it demands active engagement, conscious effort, and sustained practice.

As societies become more diverse and interconnected, the cross-race effect creates friction in contexts from international business to criminal justice to everyday social interaction. We can't simply wish away a perceptual bias rooted in neural processing. But we can acknowledge it, compensate for it, and systematically reduce it through training, exposure, and procedural reforms.

The next decade will likely bring new tools for addressing the bias. Virtual reality training programs could provide intensive perceptual practice. Artificial intelligence, trained on diverse datasets, might help us understand the specific features that distinguish faces across racial categories. Neuroscience techniques could reveal individual susceptibility to the bias, allowing targeted interventions.

For now, the most powerful tool is awareness. Every time you encounter someone from a different background, you have a choice: process them categorically or individually, rely on automatic perception or engage deliberate attention, assume your memory is reliable or acknowledge its limitations.

Six hundred milliseconds. That's how long it takes your brain to form its initial impression. What happens in the seconds, minutes, and years that follow is up to you.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

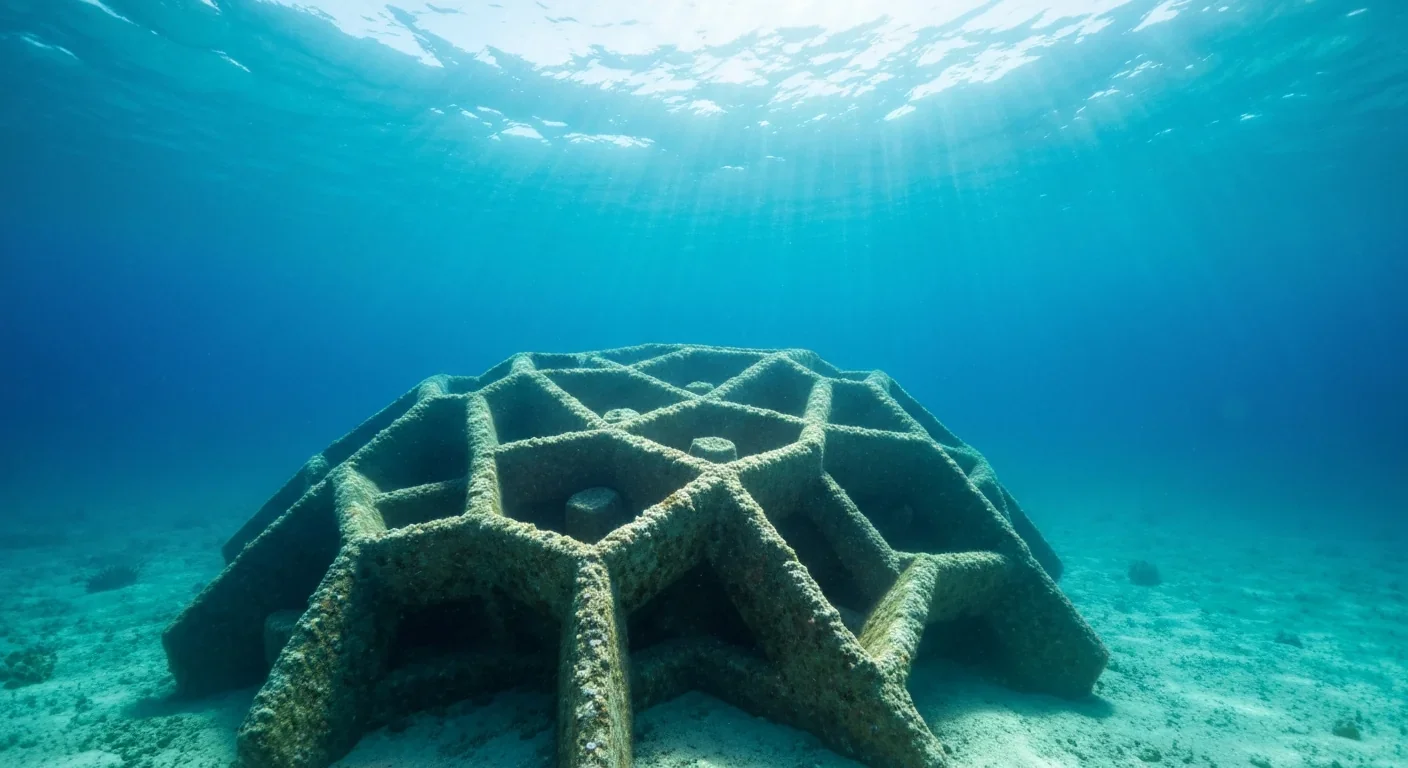

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

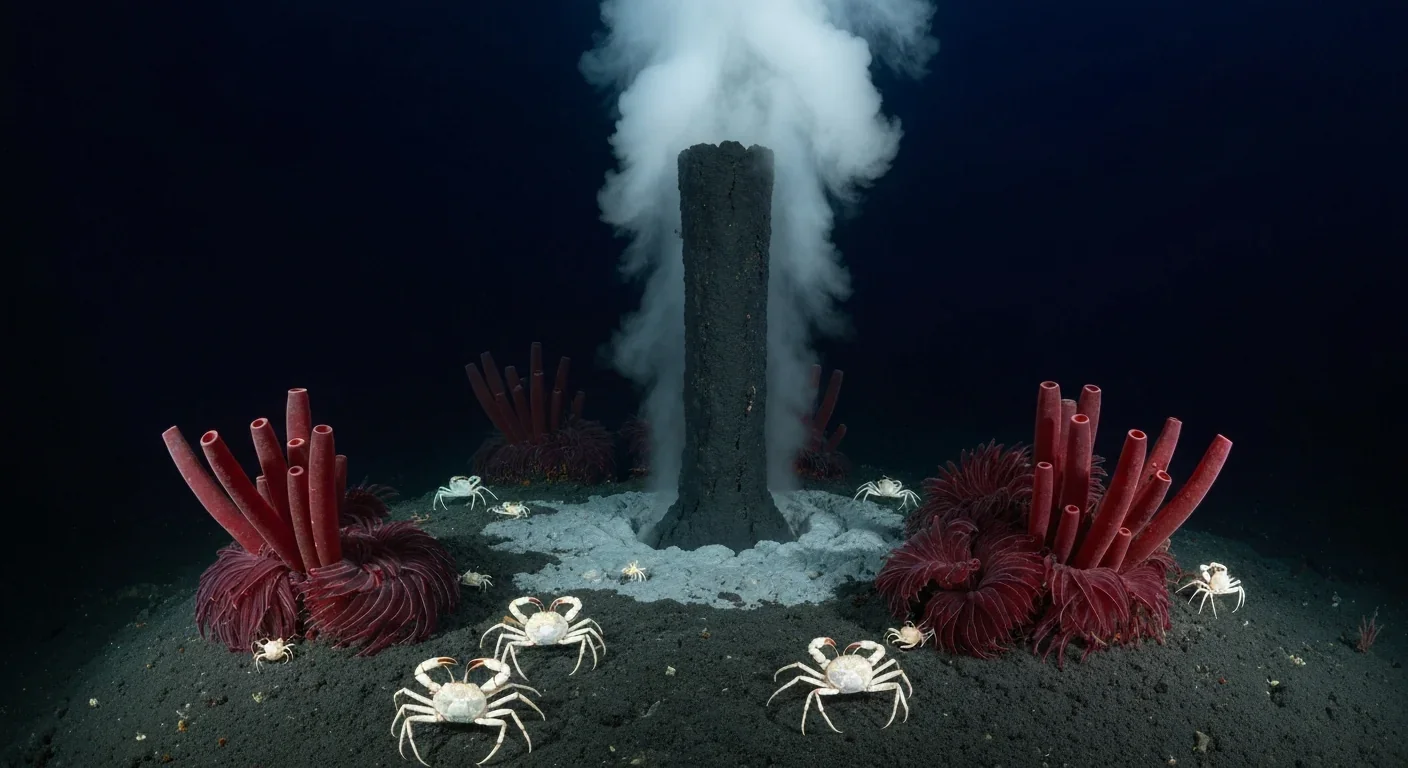

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

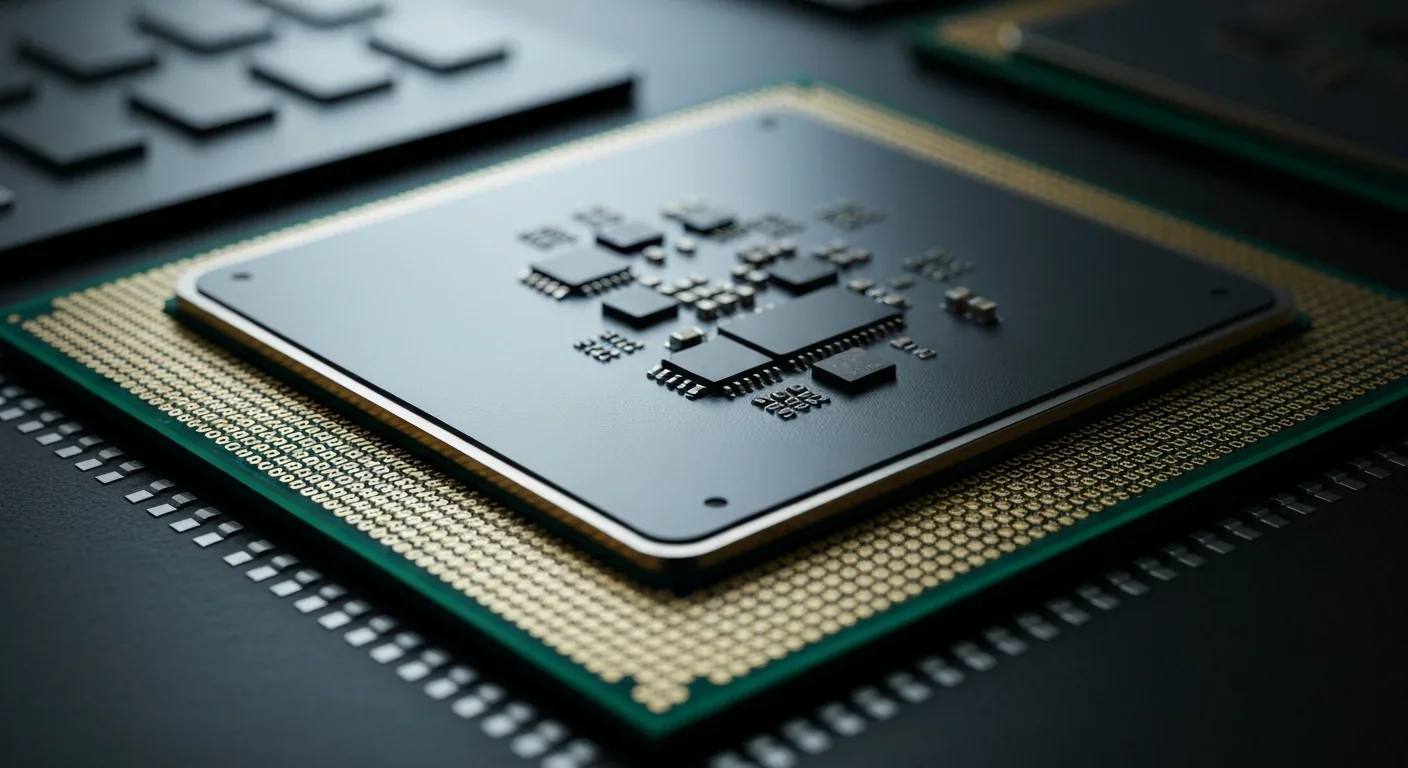

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.