The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The Dunning-Kruger effect reveals that people with limited competence systematically overestimate their abilities because the same skills needed to perform well are required to recognize good performance. This metacognitive blind spot affects everyone from novices on Mount Stupid to experts who misjudge outside their domain, but targeted calibration training and honest feedback systems can improve self-assessment.

Walk into any office, classroom, or online forum and you'll encounter them: people supremely confident in abilities they don't actually possess. They're the coworker who mansplains your own job to you, the student who skips studying because they "already know this stuff," the internet commenter convinced their five minutes of Googling trumps decades of research. What if this maddening pattern isn't just annoying - what if it reveals something fundamental about how human minds assess their own capabilities?

In 1999, psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger published research that would name this phenomenon and transform our understanding of self-awareness. Their findings: people at the bottom of the competence scale consistently rate themselves far higher than their actual performance warrants. The least skilled are often the most confident. This isn't just ignorance - it's a metacognitive blind spot that affects everyone from scuba divers to surgeons, from managers to machine learning engineers.

Dunning and Kruger didn't set out to study incompetence. They were investigating a puzzle: why do people make such poor decisions about their own abilities? Their experimental design was elegantly simple. They tested Cornell undergraduates on humor, grammar, and logical reasoning, then asked participants to estimate their performance and rank themselves against peers.

The results were striking. Students who scored in the bottom quartile - meaning they performed worse than 75% of their peers - estimated they'd done better than 60% of others. They weren't just wrong. They were catastrophically, systematically wrong in a specific direction. The gap between perceived and actual ability was largest precisely where competence was lowest.

But here's what made the finding profound: these same low performers couldn't recognize competence in others. When shown the test answers of top performers, they couldn't distinguish them from poor answers. The very skills needed to produce correct answers were the same skills needed to recognize what a good answer looked like. It was a double curse - incompetence plus the inability to recognize incompetence.

The very skills needed to produce correct answers were the same skills needed to recognize what a good answer looked like - creating a double burden of incompetence plus inability to recognize incompetence.

The original paper, titled "Unskilled and Unaware of It," became one of psychology's most cited works. It won an Ig Nobel Prize - an honor for research that "first makes people laugh, then makes them think." The name stuck: the Dunning-Kruger effect entered popular consciousness as shorthand for clueless overconfidence.

To understand why incompetence breeds confidence, you need to understand metacognition - thinking about thinking. Metacognition operates on two levels: monitoring (assessing what you know) and control (regulating how you learn). When you study for an exam, you're using metacognitive monitoring to decide which topics need more review. When you realize you don't understand something and change strategies, that's metacognitive control.

The catch: accurate metacognition requires the very expertise being assessed. You need to know enough about a domain to recognize what you don't know. Novices lack the reference points that make accurate self-assessment possible. They don't know what good looks like, so they can't judge how far they are from it.

Think of it like trying to assess your chess skills having only played against your nephew. You win every game. You feel competent. Then you play a tournament and get demolished in twelve moves. You lacked the chess knowledge to realize your nephew is terrible, which made your victories meaningless as benchmarks. Metacognitive accuracy depends on domain knowledge, creating a circular problem for beginners.

Research shows that metacognitive skills correlate only modestly with IQ. You can be intelligent and still have poor self-assessment in domains where you lack experience. This explains why brilliant people can be hilariously overconfident outside their expertise - the physicist who thinks climate science is simple, the engineer who believes education research is just common sense.

If you plot competence against confidence, you get a revealing pattern. Absolute beginners start with appropriate uncertainty - they know they know nothing. But as soon as people acquire rudimentary knowledge, confidence spikes dramatically while competence barely budges. This is "Mount Stupid," the peak of inflated assessment.

As learning continues, reality intrudes. People discover edge cases, exceptions, complexities they hadn't imagined. Confidence drops into the "Valley of Despair" as learners realize how much they don't know. Only with sustained practice does genuine competence develop, and confidence gradually rises again - this time calibrated to actual ability. Experts reach a plateau of modest confidence, tempered by awareness of the field's true complexity.

This curve isn't hypothetical. It appears across domains from scuba diving to software development to medical diagnosis. Divers with 25-50 logged dives report higher confidence than those with 100+ dives. Junior developers propose sweeping architectural changes while senior developers hedge their recommendations with caveats.

The mechanism is informational. Early learning provides just enough knowledge to attempt tasks and appear (to yourself) functional. You know the jargon, the basic moves, enough to produce output that looks superficially correct. What you lack is the pattern recognition to spot subtle errors, the experience to anticipate edge cases, the wisdom to question your assumptions. Overconfidence often manifests as overestimation of ability, overplacement relative to others, or overprecision in predictions - all reflect miscalibration between self-assessment and reality.

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn't confined to psychology labs. It shapes outcomes across every domain where competence matters.

In workplace settings, overconfident employees may volunteer for tasks beyond their capabilities, creating delays and quality issues. They resist feedback because they don't recognize its validity. Meanwhile, high performers underestimate themselves, creating the perverse dynamic where the least qualified people promote themselves most aggressively while the most qualified hold back.

Management faces a particular challenge. Leaders who assume team competence enable growth, while those who assume incompetence create it through micromanagement and learned helplessness. Yet unchecked overconfidence in teams leads to disaster. The solution isn't simple skepticism - it's creating environments where honest self-assessment is rewarded.

"Deficits or distortions in metacognition can influence how people respond to feedback, tests, and interventions - creating cascading effects on learning and performance."

- Cogn-IQ Metacognition Research

The effect appears in education constantly. Students who cram the night before exams feel confident despite poor retention because they confuse familiarity (having seen the material) with understanding (being able to apply it). Those who accurately judge their understanding allocate study time more effectively, creating a compounding advantage over time.

In UX design, clients often overestimate their understanding of design principles while designers overestimate their understanding of user needs. Both forms of overconfidence create friction. The designer dismisses client feedback as naive; the client dismisses design rationale as unnecessary complexity. Projects succeed when both sides cultivate appropriate humility about what they don't know.

Healthcare provides sobering examples. Overconfident diagnoses lead to medical errors. Studies show overconfidence persists even with detailed, continuous feedback, suggesting that experience alone doesn't cure the bias. Systematic calibration training - where practitioners explicitly compare their confidence judgments to outcomes - is necessary.

Even scuba diving illustrates the stakes. Divers in the overconfidence zone attempt dives beyond their skill level, leading to dangerous situations. Dive training increasingly incorporates explicit metacognitive components: teaching divers not just skills but how to accurately assess their own capabilities under stress.

No psychological finding this influential escapes scrutiny, and the Dunning-Kruger effect has attracted serious methodological criticism. The central challenge: is this a real psychological bias or a statistical artifact?

Critics point to regression to the mean. If performance has any randomness, low scorers who overestimate their performance might just be experiencing bad luck on the test but accurately assessing their typical ability. The correlation between their estimate and actual performance would show the Dunning-Kruger pattern without any metacognitive deficit.

More damning: the effect might be autocorrelation - a mathematical inevitability when you plot a variable against a variable that includes itself. If you ask people to estimate percentile ranking and compare it to actual percentile ranking, the apparent overconfidence of low performers and underconfidence of high performers could emerge purely from noise, without any systematic bias in self-assessment.

Research mathematician Edward Nuhfer argued the effect could be largely explained by statistical properties of the measurements rather than psychological mechanisms. When he simulated random self-assessments, the Dunning-Kruger curve appeared automatically. This doesn't mean the effect is fake - but it suggests the magnitude might be exaggerated and the mechanism might differ from the metacognitive story.

Defenders respond that the effect persists across different experimental designs that control for these artifacts. Designing tests that avoid fake Dunning-Kruger patterns requires careful attention to noise, floor effects, and ceiling effects, but it's possible. Studies using peer assessment rather than self-ranking show similar patterns. Cross-cultural replications find the effect in diverse populations.

The debate highlights an important nuance: the Dunning-Kruger effect likely combines real metacognitive deficits with statistical tendencies that amplify the apparent gap - making observed patterns more extreme than either mechanism alone would produce.

The debate highlights an important nuance: the Dunning-Kruger effect likely combines real metacognitive deficits with statistical tendencies that amplify the apparent gap. Both better-than-average bias and metacognitive incompetence contribute, making observed patterns more extreme than either mechanism alone would produce.

David Dunning himself acknowledges the complexity. In recent interviews, he notes that the effect is often misused as a cheap insult rather than a call for intellectual humility. The point isn't that incompetent people are stupid - it's that incompetence creates systematic blind spots that affect everyone, including experts outside their domain.

Here's the twist: the Dunning-Kruger effect isn't just about novices. Experts face their own calibration challenges, often in the opposite direction.

Highly skilled individuals sometimes underestimate their relative advantage because they assume tasks easy for them are easy for everyone. This false consensus effect leads experts to underestimate how much their expertise matters. The programmer who considers a task "trivial" can't imagine others struggling with it. The academic who finds a concept "obvious" forgets that expertise made it obvious.

But experts also show overconfidence, particularly through overprecision - excessive certainty in judgments. Experienced professionals often provide narrower confidence intervals than their accuracy warrants. The surgeon who has performed a procedure a thousand times might underestimate surgical risk for a complex case. The meteorologist with decades of experience might express more certainty in a forecast than the inherent uncertainty of weather systems allows.

Research on expert overconfidence reveals domain-specific patterns. In forecasting, experts often perform worse than simple statistical models while remaining highly confident. In clinical judgment, experienced physicians show overconfidence in diagnoses, especially for complex cases. The confidence-competence gap never fully closes - it just takes different forms.

The illusion of control affects experts particularly strongly. Success creates the belief that you've mastered variables that might actually involve significant luck or external factors. The expert investor who outperforms for years might attribute success to skill when market conditions played a major role. When conditions change, overconfidence in the old playbook leads to losses.

Expertise creates another blind spot: motivated reasoning. Experts invested in particular theories or methods defend them beyond what evidence supports. The Nobel laureate who makes absurd claims outside their field exhibits the Dunning-Kruger effect - expertise in physics doesn't confer expertise in biology, but success in one domain breeds confidence across domains.

If metacognitive deficits drive overconfidence, can targeted feedback fix it? The answer is complex and somewhat discouraging.

Simple performance feedback - telling someone they performed poorly - often doesn't reduce overconfidence. People rationalize away negative feedback as resulting from bad luck, biased evaluation, or irrelevant criteria. Dunning and Kruger demonstrated this directly: when they gave participants training that improved their skills, suddenly those same people could recognize how poorly they'd performed initially. The skills that improve performance also improve self-assessment.

This creates a bootstrapping problem. You can't see your incompetence until you become competent. You won't seek competence if you think you're already competent. External feedback can break the cycle - but only if the person trusts the source, values the domain, and has sufficient humility to consider they might be wrong.

"Training in metacognitive skills has been shown to improve self-assessment accuracy in experimental settings - suggesting calibration is teachable when approached systematically."

- Cogn-IQ Research on Metacognitive Training

Effective feedback interventions share common features. They're specific rather than general, focusing on particular skills or judgments. They're immediate, allowing connection between action and outcome. They're comparative, showing not just that performance was poor but how it compared to good performance. Continuous, detailed feedback helps but doesn't eliminate overconfidence - calibration requires deliberate reflection.

Metacognitive training shows promise. Instead of just teaching domain knowledge, programs that teach learners to monitor their own understanding improve self-assessment accuracy. Students learn to test themselves, predict their performance, and compare predictions to outcomes. Over time, calibration improves. The technique works because it treats metacognition as a teachable skill rather than assuming it develops automatically with expertise.

Research on children's uncertainty monitoring reveals that even seven-year-olds can learn to calibrate confidence with repeated feedback. The plasticity of metacognitive skills suggests intervention is possible across the lifespan. The challenge is creating systems that provide appropriate feedback loops.

The Dunning-Kruger effect doesn't operate in isolation - organizational and cultural contexts amplify or suppress it.

Psychological safety is essential for accurate self-assessment. In environments where admitting ignorance is punished, people double down on false confidence. When uncertainty is stigmatized, everyone pretends to know more than they do. Conversely, cultures that reward asking questions and admitting limits enable more honest self-assessment.

Power dynamics matter enormously. In client-designer relationships, clients often overestimate design understanding while designers overestimate user understanding. The client has positional authority; the designer has domain expertise. When neither side acknowledges its blind spots, projects fail. Successful collaborations explicitly address the metacognitive challenge: creating structures where both sides can safely express uncertainty.

Leadership represents a particularly dangerous context for unchecked overconfidence. Leaders who fall victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect make poor strategic decisions, resist advice, and create toxic cultures. The higher someone rises, the less critical feedback they receive, creating an echo chamber of confirmation. Board oversight and 360-degree feedback mechanisms help, but only if leaders actually value and act on the input.

Organizations can institutionalize calibration through regular prediction exercises. Before projects, team members estimate timelines, costs, and quality outcomes. After completion, they compare predictions to reality. Over time, forecasting improves as people see their biases. The key is making reflection systematic rather than assuming experience automatically improves judgment.

Cultural variation in the effect remains understudied but appears significant. Collectivist cultures may show less individual overconfidence but more in-group bias - overestimating the abilities of one's own cultural or organizational group. The manifestation changes but the underlying metacognitive challenge persists across cultures.

Artificial intelligence creates a new twist: users fall into a "reverse Dunning-Kruger trap" where AI assistance makes them feel more competent while actually reducing their understanding.

Someone using AI to generate code might feel productive and knowledgeable because the output looks professional. But without understanding the underlying logic, they can't debug effectively, assess security implications, or maintain the system. The AI has automated away the learning process that builds genuine competence. Users experience artificially inflated confidence based on AI-assisted output rather than personal capability.

AI creates a metacognitive crisis: traditional markers of competence - producing output, completing tasks - now disconnect from understanding. You can generate expert-level output without expert-level knowledge.

This creates a metacognitive crisis. Traditional markers of competence - producing output, completing tasks - now disconnect from understanding. You can generate a sophisticated legal memo without understanding law, write complex code without programming knowledge, create compelling marketing copy without grasping persuasion principles. The output quality obscures the competence gap.

The risk extends to expertise evaluation. When AI can produce expert-level output in seconds, how do non-experts judge actual expert quality? If you can't distinguish between AI-generated legal analysis and a real lawyer's work, you can't assess whether the lawyer you hired is competent. The rise of anti-expertise movements partly reflects this collapse in traditional competence signals.

The solution isn't rejecting AI but reconceptualizing competence. In an AI-augmented world, metacognitive skills become more valuable, not less. The crucial ability is knowing what you don't know, recognizing when AI output needs expert review, and maintaining humble awareness of your own limitations. As AI handles routine cognition, human value shifts toward metacognition, judgment, and wisdom - precisely the capacities undermined by the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Given that everyone is susceptible to metacognitive blind spots, what actually works for improving self-assessment?

First, cultivate specific rather than general self-evaluations. Don't ask "Am I good at programming?" Ask "Can I implement a binary search tree? Debug a race condition? Optimize database queries?" Granular assessment reduces overconfidence because it's harder to maintain inflated views across dozens of specific skills.

Second, seek objective performance measures. Subjective feelings of mastery are unreliable. Test yourself under realistic conditions. If you think you're a good public speaker, record yourself and watch it. If you believe you understand a concept, try teaching it or writing about it without references. The gap between perceived and actual performance becomes undeniable.

Third, actively seek out people who are genuinely better than you. Spend time with experts. Watch them work. Exposure to excellence recalibrates your internal standards. The intermediate tennis player feels competent until they hit with a touring pro and realize what the game actually looks like at the highest level.

Fourth, practice predicting your performance before you see results. Before submitting work, estimate the grade. Before a presentation, predict audience reaction. Before a project, forecast the timeline. Then compare predictions to outcomes. This deliberate calibration exercise improves metacognitive accuracy over time.

Fifth, cultivate intellectual humility as a virtue. Frame confidence appropriately based on your actual knowledge base. It's fine to be uncertain. It's good to say "I don't know." Strong opinions should require strong evidence, and strong evidence requires significant domain expertise. Holding views lightly in areas where you lack expertise isn't weakness - it's rationality.

Sixth, create feedback loops. Don't just complete tasks and move on. Review what went well and what didn't. Ask why you made particular decisions. Solicit input from people whose judgment you trust. The difference between experience and expertise is reflection - experience alone can reinforce overconfidence if you never critically examine your performance.

The Dunning-Kruger effect matters because it reveals an uncomfortable truth about human cognition: our minds aren't naturally good at self-assessment. We don't have direct access to our own competence levels. We construct estimates based on limited and biased information, using the very capabilities we're trying to assess.

This creates a fundamental asymmetry. Incompetence is invisible to the incompetent but glaringly obvious to the competent. Conversely, the difficult parts of expertise - the nuanced judgments, the pattern recognition, the intuitions developed over years - are invisible to outsiders who see only the easy-looking results.

The effect also highlights that ignorance isn't just missing information. It's a systematic distortion in how we perceive ourselves and others. The person who knows nothing about climate science doesn't just lack facts - they lack the framework to understand why climate science is complex, why expert consensus matters, why their brief reading doesn't constitute expertise. They suffer a dual burden: incompetence plus inability to recognize competence.

This has profound implications for how we approach learning, leadership, decision-making, and public discourse. In an era of increasing specialization, we're all novices in most domains. The challenge isn't becoming expert in everything - it's developing the metacognitive wisdom to recognize the boundaries of our competence.

The irony is that understanding the Dunning-Kruger effect doesn't immunize you against it. Knowing about the bias doesn't automatically improve self-assessment. You can be overconfident about your understanding of overconfidence. The effect is recursive: metacognitive deficits prevent recognition of metacognitive deficits.

The way forward requires humility about how little we naturally understand about our own minds. It requires building external systems - feedback mechanisms, prediction tracking, peer review, performance metrics - that reveal gaps our internal experience obscures. It requires cultural change toward valuing accurate self-assessment over confident self-promotion.

Most importantly, it requires recognizing that the person most likely to exhibit the Dunning-Kruger effect in any given situation is you. Not because you're uniquely flawed, but because you're human. The first step toward competence is recognizing how much you have yet to learn. The first step toward wisdom is recognizing how much you'll never know. And the first step toward better self-assessment is accepting that your current self-assessment is probably wrong.

The researchers who discovered the effect might have said it best: the problem isn't that people don't know things - it's that they don't know they don't know. That double negative contains the key to improvement. Recognizing that you don't know what you don't know opens the door to learning. Accepting the limits of your self-assessment enables better assessment. And maintaining appropriate humility about your expertise, even in domains where you have genuine skill, keeps you anchored to reality.

In the end, combating the Dunning-Kruger effect is a lifelong practice, not a one-time achievement. Competence shifts with experience, domains multiply, and confidence calibration requires constant adjustment. But awareness is the starting point. Understanding that your mind systematically misleads you about your abilities is the first step toward seeing more clearly. And seeing yourself more clearly is the foundation for becoming genuinely better at everything you attempt.

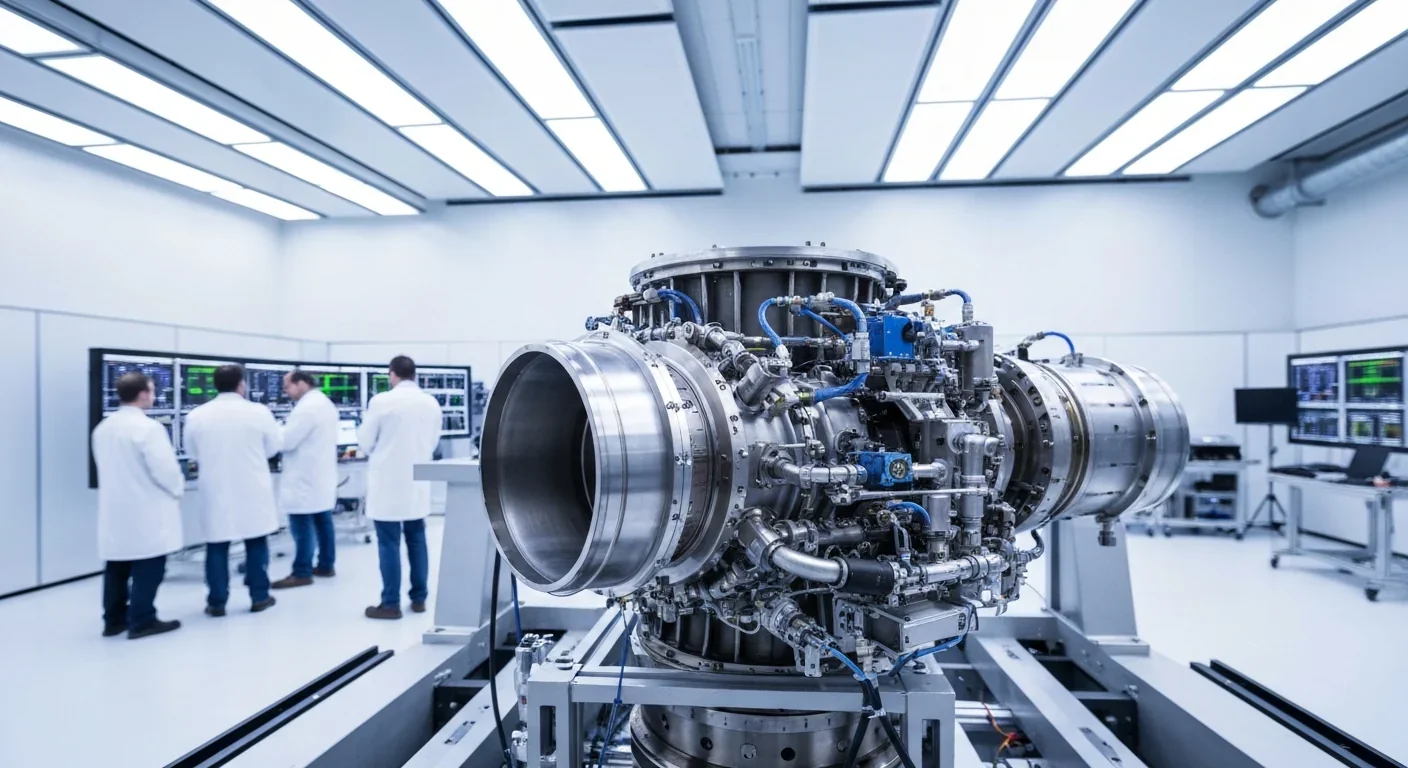

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

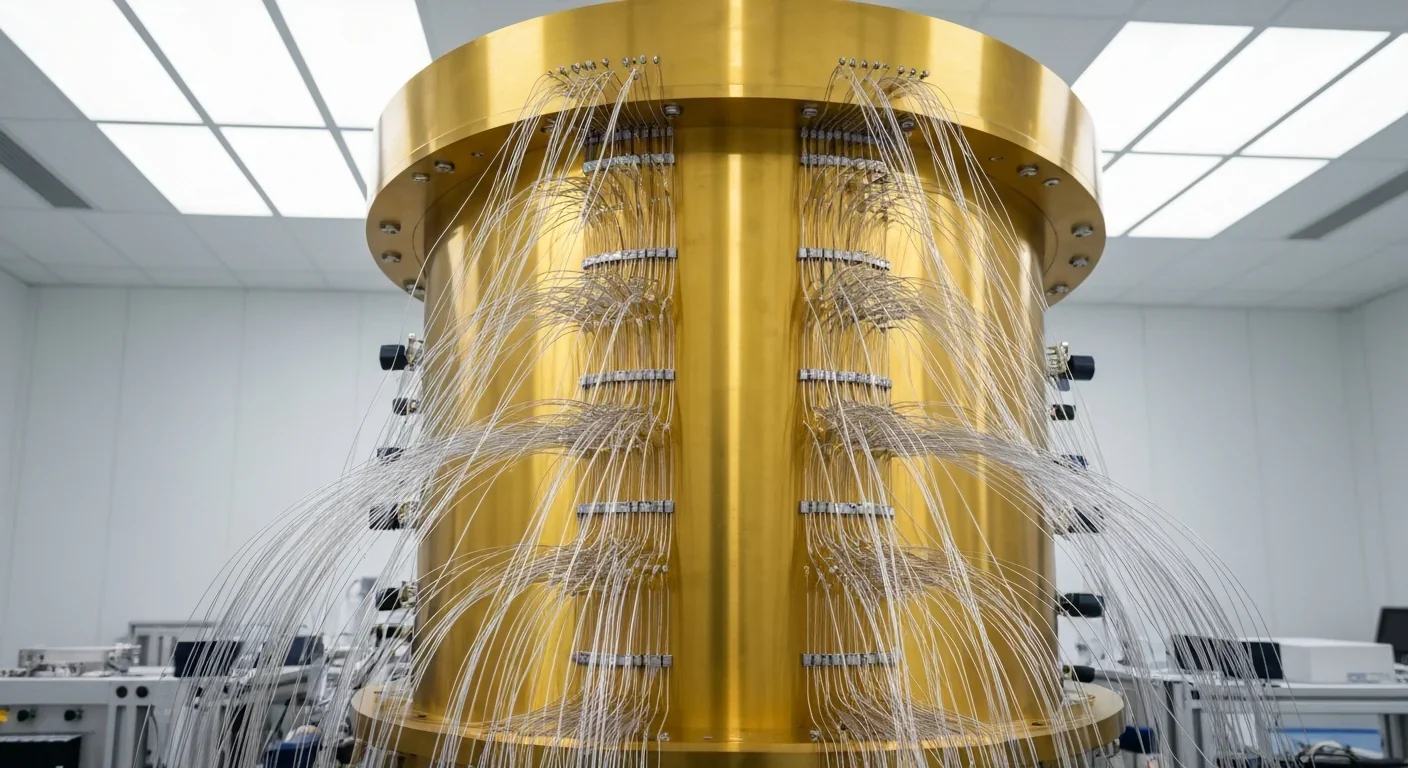

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.