The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Grandmothers aren't just family helpers but evolutionary architects of human success. By living decades past menopause, they enabled shorter birth intervals, higher child survival, and the cultural transmission that shaped our species.

Imagine a world where every human died shortly after their reproductive years ended. No grandparents to share wisdom, no elders to guide the young, no multi-generational families passing down knowledge and culture. This alternate reality almost was our reality, but evolution took a remarkable turn. Around 1.8 million years ago, something extraordinary happened in human evolution that would fundamentally reshape our species: women began living decades beyond their reproductive years, becoming grandmothers who would transform the trajectory of human success.

This evolutionary innovation, known as menopause, stands as one of nature's most puzzling phenomena. Humans share this trait with only four other species on Earth - beluga whales, narwhals, orcas, and short-finned pilot whales. But while these marine mammals developed post-reproductive lifespans in the ocean depths, our ancestors evolved this remarkable trait on the African savannah, where it would become the cornerstone of humanity's unprecedented success story.

The grandmother hypothesis, first formally proposed by anthropologist Kristen Hawkes in 1997, offers a revolutionary explanation for why humans evolved menopause and extended post-reproductive lifespans. Unlike the traditional "survival of the fittest" narrative that dominates evolutionary thinking, this theory reveals how cooperation, care, and intergenerational support became the true drivers of human evolution.

Recent research published in Biology Letters suggests an even more nuanced understanding. Scientists now believe menopause evolved through a two-step process: it started as a random byproduct of extended lifespans, then was refined and reinforced by the extraordinary benefits that grandmothers provided to their families. This "non-adaptive origins followed by evolutionary tinkering" model reconciles previously competing theories and provides a comprehensive framework for understanding this unique human trait.

The evidence supporting the grandmother hypothesis comes from multiple sources and spans millions of years of human evolution. Studies of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies provide particularly compelling data. Among the Hadza people of Tanzania, grandmothers spend 60% more time foraging for food and medicinal plants than women in their reproductive years. This isn't just casual assistance - these grandmothers are among the most productive members of their communities, often outworking younger adults in gathering critical resources.

Hadza grandmothers spend 60% more time foraging than reproductive-aged women, making them among the most productive members of their communities - a pattern that reveals the deep evolutionary logic of post-reproductive life.

The biological mechanisms underlying menopause reveal nature's sophisticated engineering. Mathematical models predict that the optimal age for reproductive cessation - around 50 years - precisely coincides with when menopause typically occurs across all human populations. This isn't coincidence; it's evolution optimizing for inclusive fitness, where helping existing offspring and grandchildren provides greater genetic returns than producing additional children.

Anthropological research has documented the profound impact of grandmothers on child survival rates. Children with living, active grandmothers are significantly more likely to survive to adulthood, even in harsh environments where infant mortality rates can exceed 50%. This survival advantage isn't just about having an extra pair of hands; grandmothers bring decades of accumulated knowledge about food sources, medicinal plants, predator behavior, and environmental patterns that can mean the difference between life and death.

The physiological changes that occur during menopause represent an evolutionary trade-off of remarkable sophistication. By shutting down reproductive capacity, the female body redirects energy and resources that would have gone toward pregnancy and nursing into other activities - foraging, teaching, caregiving, and social bonding. This reallocation of biological resources transforms post-reproductive women into survival specialists for their kin groups.

Finnish demographic data from 1900-1950 reveals that households with at least one living grandmother had an average of 1.3 more surviving grandchildren compared to households without grandmothers. Canadian census records show similar patterns, demonstrating that the grandmother effect transcends cultural boundaries and persists even in modern industrialized societies.

The story of how grandmothering shaped human evolution begins approximately 1.8 to 1.7 million years ago, during a period of dramatic climate change in Africa. As forests gave way to grasslands, our ancestors faced new challenges that would fundamentally alter their survival strategies. Food became scarcer and more widely dispersed, predators posed greater threats in open terrain, and the need for cooperative behavior intensified.

Research suggests that during this critical period, a unique combination of factors came together to create the perfect conditions for menopause to evolve. First, overall human lifespans began to increase due to better tool use, cooperative hunting, and improved nutrition. This extended longevity meant that random genetic mutations affecting late-life fertility - which had always existed but were never expressed when humans died young - suddenly became visible to natural selection.

"Our results suggest that menopause arose through a non-adaptive 'mismatch' between lifespan and reproductive span. Subsequently, an adaptive benefit drove the extension of this post-reproductive period."

- Dr. Kevin Arbuckle, Liverpool John Moores University

The second crucial factor involved changes in human social structure. As groups became more stable and cooperative, with males often remaining in their natal groups while females dispersed to mate, the stage was set for grandmothers to make significant contributions to their genetic legacy through their sons' offspring. This pattern of male philopatry, combined with female dispersal, created an environment where post-reproductive women could maximize their inclusive fitness by investing in grandchildren rather than attempting to produce more offspring of their own.

Computational models demonstrate that once grandmothering behavior emerged, it created a powerful positive feedback loop. Grandmothers who helped their daughters and daughters-in-law raise more surviving offspring spread their longevity genes through the population. Over thousands of generations, this process extended human post-reproductive lifespan from perhaps a few years to the decades we see today.

While childcare remains central to the grandmother hypothesis, the impact of post-reproductive women extended far beyond watching grandchildren. Grandmothers became the keepers of cultural knowledge, the teachers of survival skills, and the social glue that held early human communities together. They remembered where water could be found during droughts, which plants were medicinal versus poisonous, and how to read weather patterns that signaled approaching storms.

Evolutionary biologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy's research on cooperative breeding reveals another crucial dimension of grandmothering. The presence of grandmothers allowed human mothers to have shorter intervals between births - approximately three years compared to the five to seven years seen in great apes. This reproductive acceleration was only possible because grandmothers could care for weaned toddlers while mothers nursed new infants, effectively doubling the reproductive output of human females compared to our primate relatives.

The cognitive implications of grandmothering are equally profound. With grandmothers sharing the burden of childcare, human children could afford to be born more helpless and with larger, less developed brains that continued growing outside the womb. This extended brain development, supported by multigenerational care, allowed for the evolution of complex language, abstract thinking, and the sophisticated social cognition that defines our species.

Grandmothers also played a crucial role in developing and transmitting cultural innovations. Archaeological evidence suggests that many technological breakthroughs in human prehistory - from food processing techniques to medicinal preparations - may have originated with post-reproductive women who had both the time and accumulated knowledge to experiment with new methods. These innovations, passed down through generations, created a cumulative cultural evolution that accelerated human development far beyond what genetic evolution alone could achieve.

The presence of grandmothers allowed human mothers to have babies every three years instead of the five to seven years seen in great apes, effectively doubling human reproductive output and accelerating our species' success.

The evolution of menopause in cetaceans provides fascinating comparative evidence for the grandmother hypothesis. Killer whale grandmothers, like their human counterparts, play vital roles in their pod's survival. During salmon scarcity, post-reproductive female orcas lead their pods to feeding grounds, using decades of accumulated knowledge about seasonal patterns and ocean currents. Studies show that adult male orcas with living mothers are significantly more likely to survive, especially during food shortages.

The similarities between human and cetacean menopause evolution are striking. Both evolved in species with complex social structures, extended parental care, and cultural transmission of knowledge. Both involve females who stay with their natal groups while males disperse, creating conditions where older females become increasingly related to group members over time. And in both cases, post-reproductive females contribute to group survival through leadership, knowledge sharing, and direct care of younger generations.

Yet important differences exist. While cetacean menopause appears linked primarily to avoiding reproductive competition between mothers and daughters who remain in the same pod, human menopause evolved in a context of cooperative breeding where multiple females could reproduce simultaneously without direct competition. This distinction helps explain why human grandmothers became so deeply integrated into childcare and provisioning roles that are less prominent in cetacean societies.

Recent phylogenetic analyses comparing menopause across 26 mammal species reveal that the trait evolved independently at least twice - once in certain toothed whales and once in humans. This convergent evolution suggests that despite the costs of losing reproductive capacity, the benefits of post-reproductive life can outweigh those costs under specific ecological and social conditions.

Despite compelling evidence, the grandmother hypothesis faces several challenges and competing explanations. The mother hypothesis argues that menopause evolved primarily to protect older mothers from the increasing risks of late-life pregnancy, rather than to promote grandmothering. Proponents point out that pregnancy and childbirth risks increase dramatically with maternal age, and that menopause might simply be evolution's way of preventing dangerous late-life pregnancies.

Another challenge comes from the reproductive conflict hypothesis, which suggests menopause evolved to reduce competition between generations. In species where multiple generations of females breed simultaneously, younger females typically have higher reproductive success. By ceasing reproduction, older females avoid competing with their daughters and daughters-in-law for resources and mates.

Critics also point to populations where grandmothers have little contact with grandchildren due to cultural practices or geographic dispersion. If grandmothering were essential to human evolution, they argue, we should see negative fitness consequences in populations without strong grandmaternal investment. However, defenders of the hypothesis counter that modern environments differ drastically from the ancestral conditions under which menopause evolved.

The mismatch hypothesis offers yet another perspective, suggesting menopause is simply a byproduct of modern extended lifespans that evolution never anticipated. According to this view, ancestral humans rarely lived long enough to experience menopause, making it invisible to natural selection. Recent evidence, however, shows that even in prehistoric populations, a significant percentage of women who survived to adulthood also survived to post-reproductive ages, making this explanation less likely.

Understanding the evolutionary origins of grandmothering has profound implications for contemporary society. As developed nations face aging populations and changing family structures, recognizing the deep evolutionary significance of grandparents challenges us to reconsider how we organize society, structure healthcare, and support families.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated the continued importance of grandparents in modern life. When lockdowns separated grandparents from grandchildren, millions of families struggled with childcare, emotional support, and the transmission of family knowledge and values. The crisis revealed that despite technological advances and social changes, the grandparent-grandchild bond remains a fundamental human need rooted in millions of years of evolution.

Modern research on grandparenting confirms its continued benefits. Studies show that children who have regular contact with grandparents display better social skills, emotional regulation, and academic performance. Grandparents provide not just practical support but also unique perspectives, unconditional love, and connections to family history that parents, focused on immediate survival and success, may not have time to provide.

The grandmother hypothesis also has implications for understanding modern health challenges. The timing of menopause - around age 50 - evolved when human lifespans were shorter and when post-reproductive women remained physically active through foraging and childcare. Today's longer lifespans and sedentary lifestyles create a mismatch between our evolved biology and modern environment, contributing to health issues like osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline that were rare in ancestral populations.

"Grandparents are more than just loving family members - they are one of evolution's greatest gifts."

- Paula Turke, Anthropologist

The economic value of grandmothering in contemporary society is staggering yet often invisible in traditional economic metrics. In the United States alone, grandparents provide an estimated 23 billion hours of childcare annually, representing hundreds of billions of dollars in economic value. This unpaid labor enables millions of parents to work, pursue education, and contribute to the economy in ways that would be impossible without grandparental support.

Cross-cultural studies reveal that grandmaternal investment patterns vary significantly across societies, yet the underlying benefits remain consistent. In China, paternal grandmothers traditionally move in with their sons' families to help raise grandchildren. In many African societies, maternal grandmothers play the primary grandparenting role. Despite these variations, the presence of involved grandmothers correlates with improved child outcomes across all cultures studied.

The grandmother hypothesis also sheds light on contemporary debates about retirement age and productive aging. If post-reproductive life evolved specifically for contributing to society through knowledge transfer and caregiving, then modern concepts of retirement as complete withdrawal from productive activity may be fundamentally misaligned with human nature. Many older adults report feeling most fulfilled when they can contribute their knowledge and experience to younger generations, whether through formal mentoring, grandparenting, or community involvement.

Economic models that incorporate the grandmother hypothesis suggest that societies that better utilize the knowledge and experience of post-reproductive women may have competitive advantages. Countries like Japan, facing rapid aging, are experimenting with programs that connect older adults with young families, recognizing that grandparental knowledge and care represent valuable social capital that shouldn't be wasted.

As we look toward the future, several trends will shape the evolution of grandparenting in human societies. Increasing lifespans mean that many people now become grandparents while still in their peak productive years, creating new models of active grandparenting that combine career contributions with family support. Geographic mobility and digital technology are transforming how grandparents and grandchildren connect, with video calls and social media enabling relationships across vast distances that would have been impossible for previous generations.

Climate change and environmental challenges may make grandparental knowledge increasingly valuable again. As societies grapple with resource scarcity, extreme weather, and ecosystem changes, the accumulated wisdom of older generations about adaptation, resilience, and survival may prove crucial. Indigenous communities, where grandparental knowledge about traditional ecological practices remains strong, are already demonstrating the value of intergenerational knowledge transfer in addressing environmental challenges.

Advances in reproductive technology and changing family structures are also reshaping grandparenthood. Same-sex couples, single parents by choice, and families formed through assisted reproduction are creating new configurations of grandparenting that transcend traditional biological relationships. These evolving family forms demonstrate that the essential functions of grandparenting - care, knowledge transfer, and emotional support - matter more than genetic relatedness alone.

Research on the genetics of longevity suggests that genes promoting extended post-reproductive lifespan continue to be under positive selection in human populations. As modern medicine reduces early mortality, allowing more people to reach post-reproductive ages, the genetic variants that support healthy aging and grandparenting may become even more prevalent in future generations.

The grandmother hypothesis teaches us that human success was never just about individual survival or reproduction - it was always about intergenerational cooperation and the transmission of knowledge across time. This understanding challenges simplistic narratives about human nature being fundamentally selfish or competitive. Instead, it reveals that our deepest evolutionary programming includes care for others, especially the vulnerable young who carry our genetic and cultural legacy forward.

The evolution of menopause and grandmothering also demonstrates evolution's creativity in solving complex problems. Rather than simply extending fertility to match extended lifespans, evolution found a more elegant solution: transform post-reproductive individuals into specialists who increase inclusive fitness through indirect care. This biological innovation created a new life stage unique to humans, one that continues to shape our societies millions of years after it first evolved.

Understanding our evolutionary history as cooperative breeders with essential grandmaternal care also has implications for social policy. Societies that support multigenerational families, facilitate grandparent-grandchild relationships, and value the contributions of older women may be working with, rather than against, human nature. Programs that isolate older adults from younger generations or undervalue their potential contributions may be missing opportunities to harness millions of years of evolutionary wisdom.

The story of grandmothers in human evolution ultimately reveals that our species' greatest innovation wasn't tool use, language, or even our large brains - it was the creation of multigenerational communities where knowledge, care, and resources flow between generations. As we face unprecedented global challenges requiring long-term thinking and intergenerational cooperation, the evolutionary wisdom of grandmothering may be more relevant than ever.

Societies that support multigenerational families and value the contributions of older women aren't just being sentimental - they're working with millions of years of evolutionary programming that made humans the most successful species on Earth.

The grandmother hypothesis revolutionizes our understanding of human evolution, revealing that post-reproductive women were not evolutionary dead-ends but rather the architects of human success. Through their care, knowledge, and dedication to future generations, grandmothers created the conditions for extended childhoods, larger brains, and the complex societies that define our species.

As we navigate rapid technological and social change, the deep evolutionary logic of grandmothering reminds us that human thriving depends on intergenerational bonds and the flow of wisdom from old to young. The same grandmothers who once led their families to water sources in drought-stricken savannahs now guide their grandchildren through the complexities of modern life, their role transformed but their importance undiminished.

The evidence is clear: grandmothers are not just nice to have around - they are essential to human nature, woven into our DNA through millions of years of evolution. Every human alive today descends from grandmothers who successfully raised grandchildren to adulthood, passing on not just genes but knowledge, culture, and the capacity for love that transcends individual lifespans.

Modern societies that recognize and support the grandmothering role are not being sentimental or old-fashioned - they are acknowledging a biological and cultural reality that has shaped our species for nearly two million years. As we face challenges that require long-term thinking and intergenerational cooperation - from climate change to technological disruption - the evolutionary wisdom embodied in grandmothering may hold keys to our collective future.

The next time you see a grandmother teaching a child, sharing a story, or providing comfort, remember that you're witnessing not just a heartwarming family moment but the continuation of an evolutionary strategy that transformed apes into humans and continues to shape our destiny. In a world that often seems to value youth above all else, the grandmother hypothesis reminds us that post-reproductive life is not a decline but a culmination - the stage where humans become most fully what evolution designed us to be: teachers, nurturers, and bridges between past and future.

The revolution that began on the African savannah continues today in every family where a grandmother's love, wisdom, and care nurtures the next generation. It's a revolution not of conflict but of cooperation, not of individual success but of collective thriving. And as long as humans exist, grandmothers will remain at its heart, the unsung heroes of our evolutionary success story.

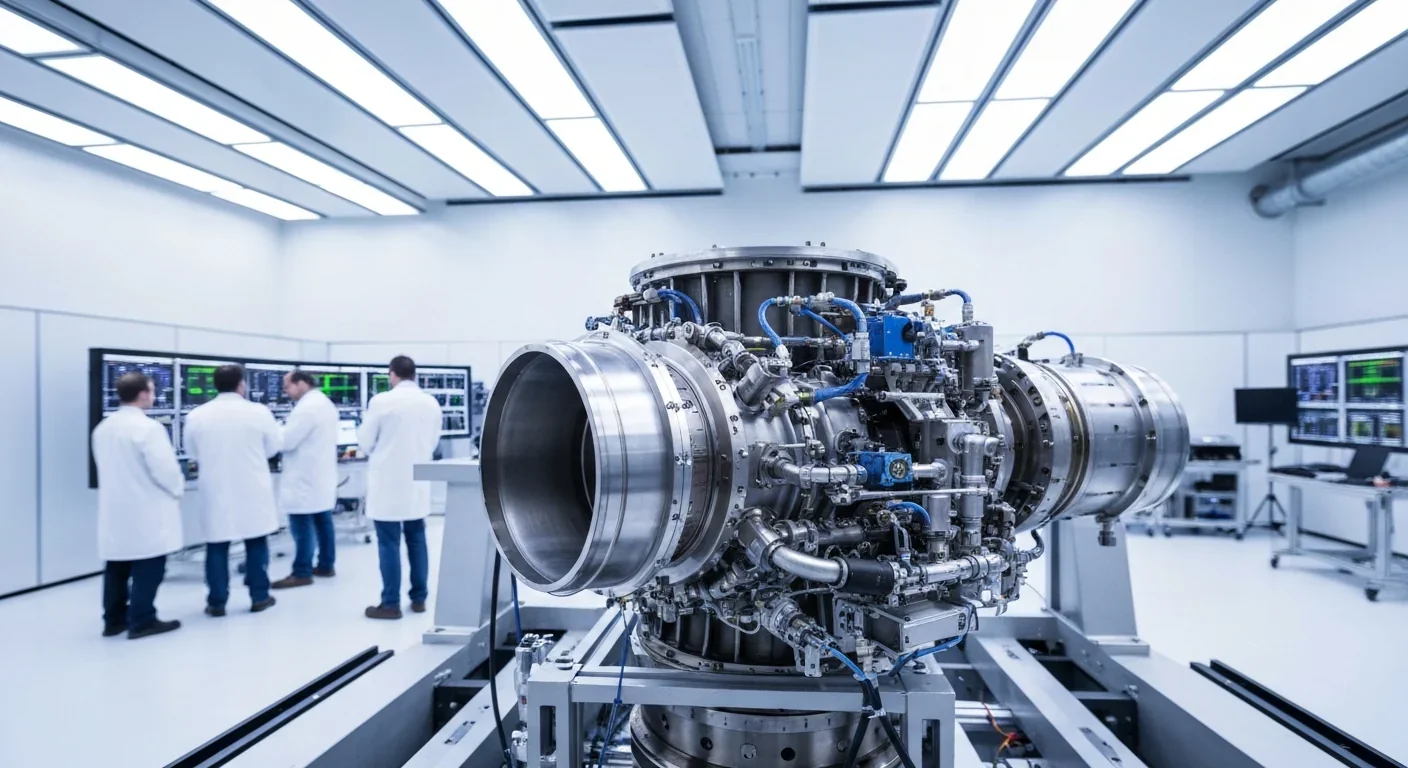

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

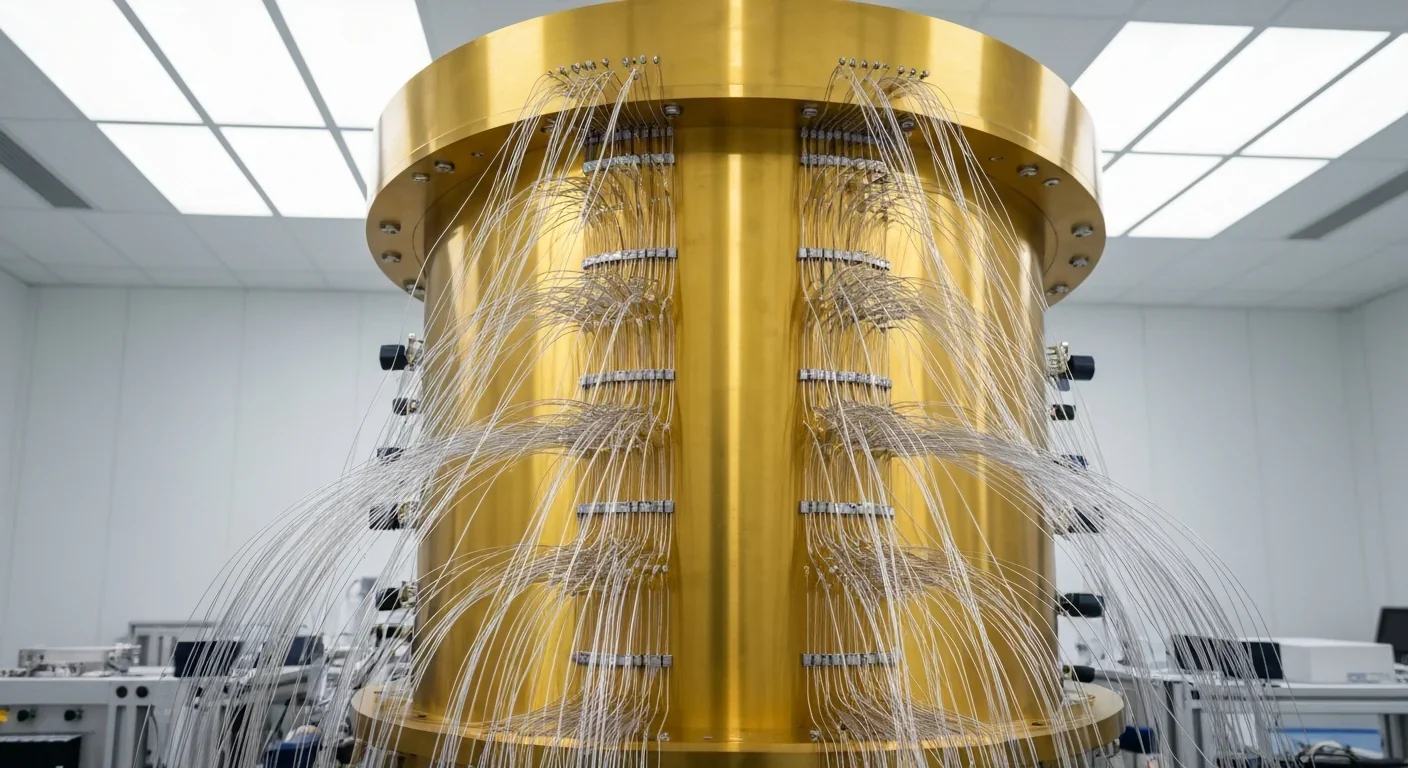

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.