The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Emotional labor - managing and performing emotions as part of work - creates enormous economic value but remains uncompensated and invisible. From healthcare to teaching to service jobs, workers face burnout from this hidden tax, with women and people of color bearing disproportionate burdens.

By 2030, economists predict that service sector jobs requiring intensive emotional management will constitute over 80% of the workforce in developed nations. Yet we still don't compensate the invisible work that makes these jobs possible. What happens when millions of workers are paid to smile, comfort, and care - but never paid for the psychological toll it takes?

The customer service representative who remains cheerful while being verbally abused. The nurse who comforts a dying patient's family while suppressing her own grief. The teacher who projects enthusiasm on day 187 of a grueling school year. These workers aren't just doing their jobs - they're performing emotional labor, a concept that has quietly become one of the most consequential yet undervalued dimensions of modern work.

In 1983, sociologist Arlie Hochschild published The Managed Heart, a groundbreaking study that would forever change how we understand work. After studying Delta Airlines flight attendants and bill collectors, Hochschild identified something that had been hiding in plain sight: certain jobs required workers to manage their emotions as a core job function, not just a nice-to-have skill.

Hochschild defined emotional labor as the process of managing feelings to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display. It's not about having emotions at work - we all do that. It's about the requirement to produce specific emotional displays as part of your job description, whether you feel those emotions or not.

The concept emerged from a simple but powerful observation: flight attendants were trained not just to serve drinks and demonstrate safety procedures, but to transmit calmness and warmth even when passengers were hostile. They were told to "think of passengers as guests in your home" and to maintain their emotional composure regardless of how they actually felt. This wasn't customer service - it was emotional performance.

What made Hochschild's insight revolutionary was recognizing that this emotional management had economic value. Companies profited from it. Customers expected it. But workers bore the cost.

What made Hochschild's insight revolutionary was recognizing that this emotional management had economic value. Companies profited from it. Customers expected it. But workers bore the cost.

Not all emotional labor is created equal. Research has identified two primary strategies workers use: surface acting and deep acting.

Surface acting is the fake-it-till-you-make-it approach. You paste on a smile, modulate your voice, and perform the required emotions while your inner feelings remain unchanged. Think of the retail worker who greets you cheerfully while internally counting the minutes until their shift ends. Surface acting creates what psychologists call "emotional dissonance" - the exhausting gap between what you feel and what you display.

Deep acting is more sophisticated. Here, workers actually try to generate the required emotions internally. The nurse who needs to project calm doesn't just fake it - she actively works to feel calm, perhaps by reframing the situation or summoning genuine empathy. It's method acting for everyday life.

Studies show these strategies have dramatically different consequences. Surface acting consistently predicts burnout, emotional exhaustion, and poor mental health. Deep acting can actually buffer against these negative outcomes, though it requires more psychological resources upfront. The problem? Most workers don't receive training in deep acting - they just learn to fake it.

Walk into any hospital, restaurant, classroom, or call center, and you'll find workers drowning in emotional labor. But some industries demand it more intensively than others.

Healthcare workers face perhaps the most demanding emotional labor requirements. Nurses must project calm during medical emergencies, comfort anxious patients, navigate family conflicts, and bear witness to suffering and death - all while maintaining professional composure. A meta-analysis found that emotional labor significantly predicts job burnout among healthcare workers, with effect sizes showing the relationship is substantial and consistent across cultures.

The pandemic magnified these demands exponentially. Healthcare workers dealt with unprecedented death tolls, resource shortages, and personal risk while being simultaneously celebrated as heroes and blamed for system failures. The emotional labor of maintaining professionalism under these conditions contributed to a mental health crisis that continues today.

Teachers perform different but equally intensive emotional labor. They must project enthusiasm and warmth, manage classroom emotions, support students' social-emotional development, and navigate conflicts with parents and administrators. Recent research on rural physical education teachers in China found that emotional labor directly predicted turnover intention through burnout, with social support offering only partial protection.

Service workers - from flight attendants to baristas to call center agents - face constant requirements to be friendly, upbeat, and accommodating. Contact centers report turnover rates as high as 40%, driven largely by the exhaustion of maintaining pleasant emotions while handling angry or frustrated customers hour after hour.

"The common thread? These jobs require sustained emotional performance with limited control over the interactions, minimal recognition of the psychological costs, and inadequate compensation for the invisible labor being performed."

- Pattern identified across service industries

The common thread? These jobs require sustained emotional performance with limited control over the interactions, minimal recognition of the psychological costs, and inadequate compensation for the invisible labor being performed.

The consequences of intensive emotional labor aren't just psychological - they're physiological. When you consistently perform emotions you don't feel, your body keeps score.

Research reveals that emotional labor correlates significantly with job burnout, with a pooled effect size of 0.289 across multiple studies. That might sound small, but in population-level studies, it represents thousands of workers pushed toward exhaustion. The relationship strengthens with surface acting and weakens with organizational support and emotional intelligence.

Surface acting specifically leads to emotional dissonance, causing psychological stress that manifests as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced sense of accomplishment - the three hallmarks of burnout. Among psychiatric nurses facing workplace violence, those who relied heavily on surface acting reported significantly worse sleep quality, creating a vicious cycle of exhaustion and reduced coping capacity.

The toll extends beyond individual wellbeing. Preschool teachers' emotional labor predicted mental health problems including depression and anxiety, with psychological capital - comprising hope, resilience, optimism, and efficacy - serving as only a partial buffer. Even with strong psychological resources, the demands eventually break through.

Compassion fatigue, a specific form of burnout affecting caring professions, emerges from the sustained empathetic engagement required by emotional labor. Healthcare workers exposed to patient death during the COVID-19 pandemic showed elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress, with emotional labor demands amplifying these effects.

The biological reality is clear: you can't indefinitely perform emotions your body isn't experiencing without paying a price.

If you're a woman reading this, you probably saw this section coming. If you're a man, you might be surprised by the depth of the disparity.

Research consistently shows that women perform more emotional labor than men, both in workplaces and at home. Women are more likely to work in occupations with high emotional labor demands - nursing, teaching, social work, customer service. Even within the same occupations, women are expected to be warmer, more nurturing, and more accommodating.

This isn't coincidental. It's the product of deeply ingrained gender socialization that trains girls to be emotion managers from early childhood. Women learn to read emotional cues, smooth over conflicts, anticipate others' needs, and maintain social harmony. These are valuable skills - they're just rarely recognized or compensated.

The workplace expectations reflect these socialization patterns. Women in the workplace are expected to remember birthdays, organize social events, mediate conflicts, provide emotional support to colleagues, and manage the "office housework" that keeps teams functioning. When women don't perform these tasks, they face social penalties. When men do perform them, they often receive disproportionate credit.

A study of gendered pathways of emotional labor in human services found that women and men approached emotional labor differently, with women more likely to engage in both surface and deep acting, while men showed more selective engagement. The expectations weren't just different - they were unequal.

The intersection of race and gender further compounds these dynamics. Black women in service industries face what researchers call an "emotional tax" - the additional burden of managing racist assumptions, microaggressions, and stereotype threat while performing the standard emotional labor of their roles. They must not only serve with a smile but also manage others' racial anxieties and biases.

Here's the uncomfortable economic reality: emotional labor creates enormous value, but most of it is captured by employers and customers rather than the workers who perform it.

Companies understand this intuitively, even if they don't use the term. That's why customer-facing roles emphasize "culture fit" and "positive attitude" in hiring. They're screening for emotional labor capacity. Airlines, hotels, and restaurants build their brands on the emotional performances of front-line workers. Healthcare organizations market themselves on compassionate care delivered by emotionally exhausted nurses.

A nurse is paid for clinical skills, not for comforting families. A teacher's salary reflects education level, not the emotional management that comprises half their actual work. The labor is real - the compensation isn't.

Yet this labor rarely appears in job descriptions or compensation structures. A nurse is paid for clinical skills and certifications, not for the emotional work of comforting families. A teacher's salary reflects education level and years of experience, not the emotional management that comprises half their actual work. A customer service representative's pay is based on call volume and resolution rates, not the psychological toll of maintaining composure through verbal abuse.

Some industries have attempted to recognize this work through empowering leadership and organizational support. Research shows that when leaders acknowledge emotional labor demands and provide resources to manage them, workers experience more job passion and less burnout. But these interventions remain rare, and they don't address the fundamental issue: the work is still uncompensated.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a stark illustration. Healthcare workers were applauded as heroes, but their emotional labor intensified dramatically without corresponding increases in compensation or systemic support. The message was clear: we value your sacrifice, just not enough to pay for it.

Economists have struggled to quantify the value of emotional labor because it doesn't fit traditional productivity metrics. How do you measure the value of a nurse's comforting presence? What's the dollar value of a teacher's enthusiasm? Yet businesses clearly believe it has value - they just prefer to extract it for free.

Awareness of emotional labor is growing, and so is pushback against the expectation that workers should provide it without recognition or support.

Healthcare organizations are beginning to implement interventions specifically targeting emotional labor demands. These include training in emotional intelligence and deep acting strategies, organizational policies that reduce emotional dissonance, and systems for acknowledging the emotional components of caregiving work. Research shows these interventions can improve both job satisfaction and patient outcomes.

Some companies are redesigning customer service roles to reduce emotional labor demands. This includes giving workers more authority to resolve problems (reducing the frustration that triggers customer hostility), rotating workers out of high-stress interactions, and explicitly acknowledging emotional labor in performance reviews and compensation.

Educational institutions are starting to address teachers' emotional labor through resilience training and peer support systems. Some schools have created positions specifically for handling difficult parent interactions, removing that burden from teachers. These changes remain piecemeal, but they represent growing recognition that emotional labor can't be ignored.

Individual workers are also pushing back. The concept of emotional labor has entered popular discourse, giving workers language to articulate what they've always experienced. Social media conversations about emotional labor, particularly among women, have raised awareness and validated experiences that were previously dismissed as "just part of the job."

Some workers are simply refusing to perform uncompensated emotional labor. They're setting boundaries around office housework, declining to manage others' emotions, and pushing back against expectations that they should always be pleasant regardless of circumstances. This "quiet quitting" of emotional labor represents a form of resistance, though it often comes with professional costs.

If you perform emotional labor - and if you work with other humans, you probably do - how can you manage it without burning out?

First, recognize what you're doing. Naming emotional labor makes it visible and validates the work involved. Many workers don't realize that the exhaustion they feel stems partly from this invisible performance. Awareness is the first step toward managing it.

Second, whenever possible, shift from surface acting to deep acting. This doesn't mean forcing yourself to feel emotions you don't - that's just another form of surface acting. It means finding genuine aspects of the situation that allow you to connect authentically. The teacher who's tired of explaining the same concept for the twentieth time might remember that each student is experiencing it for the first time. This reframe doesn't eliminate the emotional labor, but it reduces the exhausting dissonance.

"Workers need opportunities to drop the emotional performance. This might mean taking real breaks where you don't have to perform, finding peer spaces where you can be honest about your frustrations, or engaging in activities that let you experience and express authentic emotions."

- Research on coping strategies

Third, create recovery spaces. Research on coping strategies shows that workers need opportunities to drop the emotional performance. This might mean taking real breaks where you don't have to perform, finding peer spaces where you can be honest about your frustrations, or engaging in activities that let you experience and express authentic emotions.

Fourth, build boundaries. You can acknowledge emotional labor without accepting unlimited demands. This might mean saying no to office housework that's not in your job description, declining to manage a colleague's emotional crisis when you're already depleted, or leaving work at work instead of continuing emotional performance at home.

For organizations, the strategies require more systemic thinking. Research identifies several evidence-based interventions:

- Explicitly acknowledge emotional labor in job descriptions and performance evaluations

- Provide training in emotional intelligence and deep acting strategies

- Create policies that reduce emotional dissonance (like empowering customer service workers to resolve complaints)

- Rotate workers out of the most emotionally demanding situations

- Provide adequate staffing so workers aren't performing emotional labor while overwhelmed with other tasks

- Establish peer support systems and professional supervision for processing emotional demands

- Consider compensation structures that recognize emotional labor intensity

The research on university teachers found that when institutions acknowledged emotional labor and provided resources to manage it, work performance improved alongside wellbeing. Recognition and support aren't just ethical imperatives - they're practically effective.

As automation transforms the workforce, emotional labor is becoming more, not less, central to human work. The jobs that remain will increasingly be those requiring human emotional connection - precisely the jobs with high emotional labor demands.

This creates a critical juncture. Will we continue to treat emotional labor as an invisible externality that workers should provide for free? Or will we recognize it as legitimate work deserving of acknowledgment, support, and compensation?

The pandemic forced a reckoning with how we value essential workers, many of whom perform intensive emotional labor. The applause was nice, but workers need systemic change: better pay, adequate staffing, organizational support, and recognition that emotional labor is real work.

Remote work is creating new forms of emotional labor. Workers must now perform emotional displays through video calls, manage digital team dynamics, and maintain engagement through screens. The context has changed, but the demands persist.

Gender equity requires addressing emotional labor head-on. As long as women are expected to perform uncompensated emotional labor both at work and at home, equality remains theoretical. Redistributing this work requires not just individual awareness but structural change in how we value care work, organize households, and define professional success.

The conversation about emotional labor is really a conversation about what we value as a society. Do we value care, empathy, and emotional connection? If so, are we willing to compensate the people who provide them? Or will we continue to extract this labor while offering only appreciation in return?

The flight attendant who calms nervous passengers. The nurse who holds a dying patient's hand. The teacher who projects enthusiasm on the hardest days. The customer service representative who remains professional through hostility. These workers deserve more than our appreciation. They deserve recognition that what they're doing is work - invisible, exhausting, economically valuable work.

Hochschild's insight from 1983 remains urgent today: when we require people to manage their emotions as part of their job, we're asking them to commodify a part of themselves. That has costs - psychological, physical, social. Understanding emotional labor doesn't eliminate those costs, but it makes them visible. And visibility is the first step toward change.

The hidden tax on workers who perform emotional labor has been extracted for too long. The question isn't whether this work has value - employers and customers have already answered that through their demands and expectations. The question is whether we're willing to recognize, support, and compensate the people who perform it.

The future of work will be emotional. We get to decide whether it will also be humane.

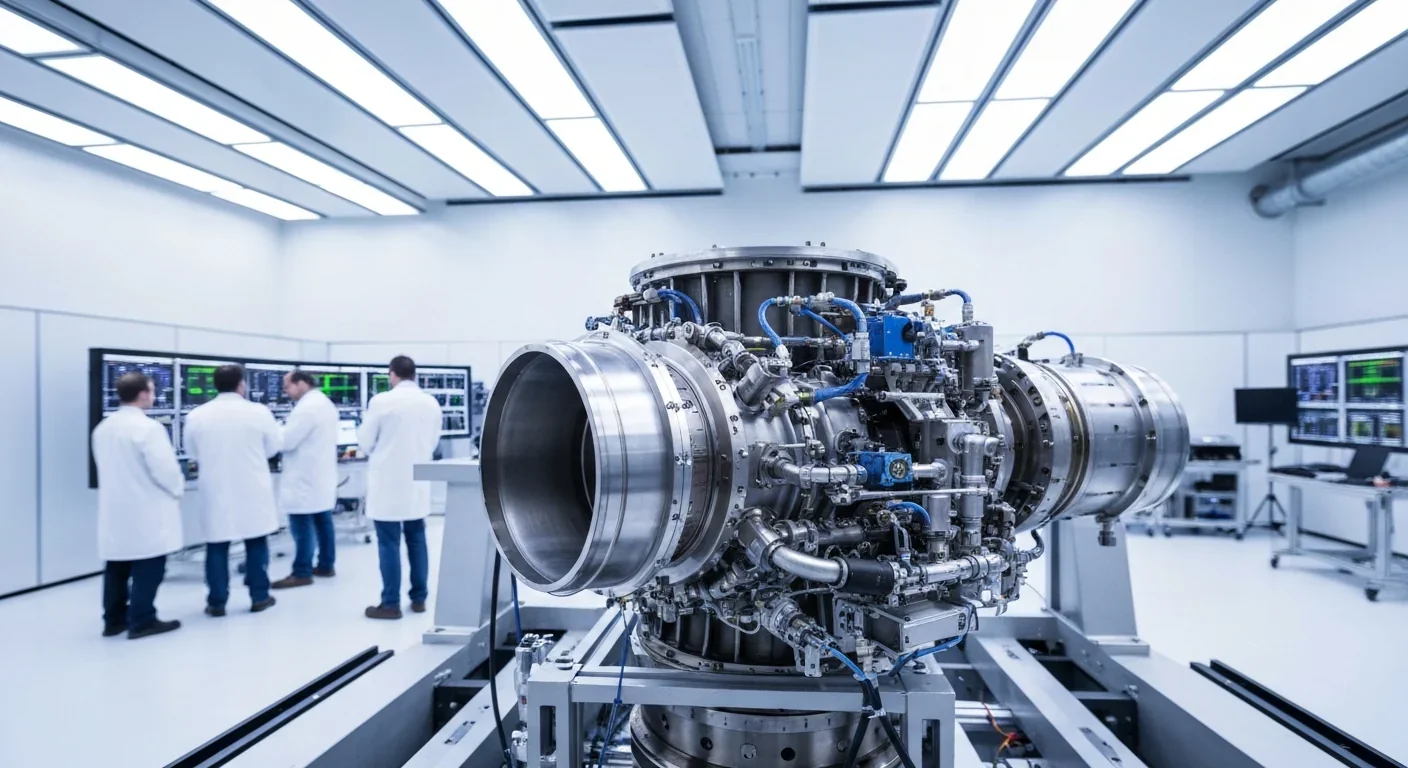

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

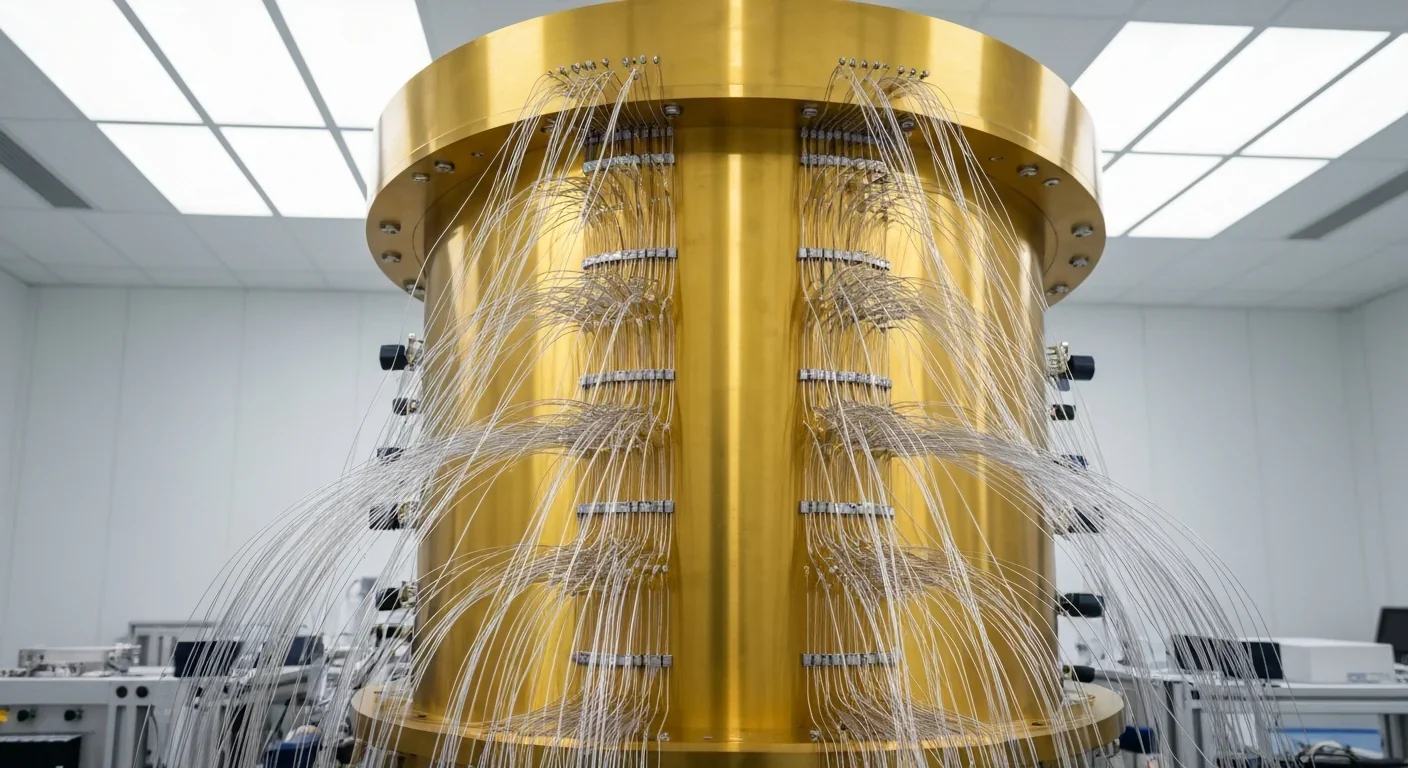

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.