The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Humans may have evolved through self-domestication - selecting for calm, cooperative individuals over thousands of generations. Like domesticated animals, we retained juvenile traits into adulthood, including smaller faces, reduced aggression, and extended learning capacity. This process reshaped both our biology and behavior, creating the foundation for language, culture, and civilization.

Imagine encountering a Neanderthal on a city street. Beyond the obvious shock, one detail would stand out: their face. Massive brow ridges, a protruding jaw, robust bone structure - features that make modern humans look almost childlike by comparison. This isn't just superficial. Scientists now argue that humans underwent a process of self-domestication, essentially breeding ourselves to be tamer, more cooperative versions of our ancestors. The result? We're basically juvenile apes who never quite grew up.

This radical reframing of human evolution - called the self-domestication hypothesis - suggests we selected for calm, prosocial individuals over thousands of generations. Just as humans bred wolves into dogs, we inadvertently bred ourselves into a new kind of primate: one defined not by physical dominance but by social intelligence, cooperation, and a peculiar retention of juvenile traits well into adulthood.

To understand human self-domestication, we need to talk about foxes. In 1959, Soviet geneticist Dmitry Belyaev launched one of evolution's most elegant experiments. He took aggressive silver foxes - animals that would bite and snarl at researchers - and bred only the calmest, least fearful individuals. Within just 40 generations, something remarkable happened.

The foxes didn't just become friendlier. They started wagging their tails. Their ears went floppy. Their snouts shortened, their skulls became rounder, and some developed patches of white fur. They began to look, act, and even think differently - more like dogs than wild foxes. Lyudmila Trut, who continued Belyaev's work for decades, described them as transforming from "fire-breathing dragons" into animals as friendly as golden retrievers.

Selecting for a single behavioral trait - tameness - can trigger a cascade of physical changes across multiple body systems. This is the domestication syndrome, and it appears in every species humans have domesticated.

This suite of changes - smaller faces, floppy ears, reduced aggression, playfulness - is called domestication syndrome. It appears across domesticated species: dogs, pigs, cattle, even cats. What's stunning is that selecting for a single trait (tameness) triggers this whole cascade of physical and behavioral shifts.

The key insight? Domestication isn't just about behavior. It rewires development itself.

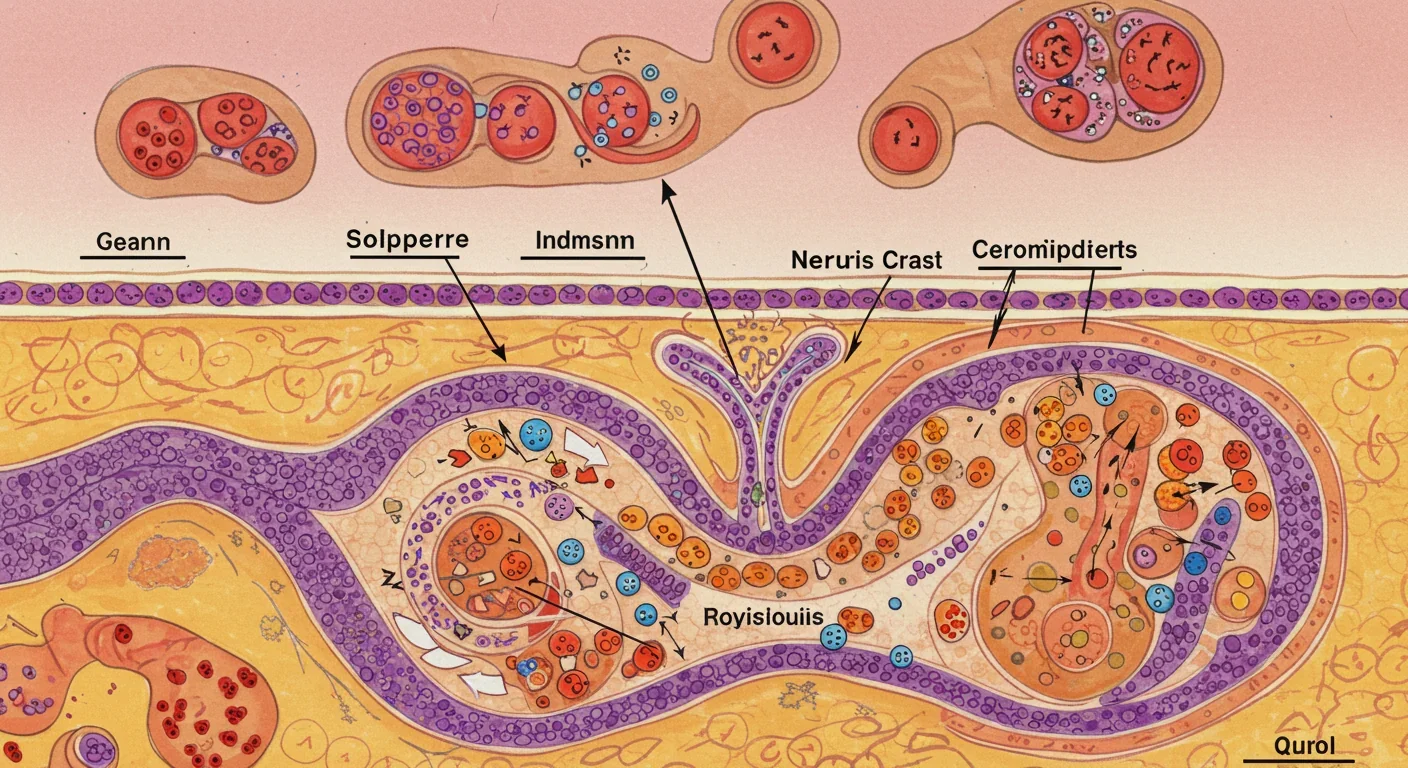

Here's where it gets fascinatingly technical. In 2014, evolutionary biologists Adam Wilkins, Richard Wrangham, and Tecumseh Fitch proposed a unified explanation for domestication syndrome. The common thread linking smaller faces, floppy ears, and reduced aggression? Neural crest cells.

These are embryonic cells that migrate throughout the developing body, forming everything from facial bones to pigmentation, adrenal glands to parts of the nervous system. When you select for tameness, you're selecting against reactive aggression - which means selecting for animals with lower stress hormones. Lower stress hormones mean fewer neural crest cells during development.

Fewer neural crest cells translate into:

Smaller, more gracile skulls (less bone deposition)

Shorter snouts and flatter faces (reduced facial projection)

Floppy ears (less cartilage)

Changes in coat color (altered pigmentation)

Reduced adrenal gland size (lower cortisol production)

This developmental bottleneck - where a single change in cell migration cascades into dozens of physical traits - explains why domesticated animals consistently share these features. It's not multiple separate mutations. It's one mechanism affecting many outcomes.

And humans? We show the exact same pattern.

Compared to our extinct cousins - Neanderthals, Denisovans, even earlier Homo species - modern humans are gracile. Our skulls are thinner, our brow ridges nearly nonexistent, our jaws smaller and our faces flatter. We look, in many ways, like juvenile versions of more robust hominins.

This retention of juvenile features into adulthood is called neoteny. And it's not just physical. Behaviorally, humans are the playful, curious, socially tolerant apes. We maintain traits that in other primates fade after childhood: extended learning periods, low reactive aggression, high social bonding.

"Modern humans are docile and tolerant, like domesticated species. Our cooperative abilities and pro-social behaviour are key features of our modern cognition."

- Cedric Boeckx, Researcher

A 2017 genetic study found something striking. Researchers compared genes under positive selection in modern humans with those in domesticated animals. There was significant overlap - but only with modern humans. Not with Neanderthals. Not with chimpanzees, gorillas, or orangutans. The genetic signature of domestication appears unique to Homo sapiens.

Lead researcher Cedric Boeckx put it bluntly: "Modern humans are docile and tolerant, like domesticated species. Our cooperative abilities and pro-social behaviour are key features of our modern cognition."

The fossil record tells a story of gradual gracilization. Over the past 80,000 to 100,000 years, human skulls became progressively less robust. Brow ridges shrank. Faces flattened. But a particularly sharp transition occurred between 40,000 and 25,000 years ago - right when complex culture, symbolic art, and advanced toolmaking exploded across continents.

This timing isn't coincidental. Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist at Harvard, argues that self-domestication created the conditions for cultural evolution. Lower reactive aggression meant tighter cooperation. Tighter cooperation enabled language, shared learning, and cumulative culture. These created further selection pressure for individuals who could navigate complex social networks.

It became a feedback loop: social groups selected against the most aggressive individuals (through exclusion, execution, or mate choice), which made groups more cooperative, which increased the value of social intelligence, which selected for even more prosocial traits.

Think of it as evolution by capital punishment and gossip. Communities that could coordinate to remove dangerously aggressive individuals would have thrived. Those individuals didn't pass on their genes. Over thousands of generations, this steady filtering reshaped not just behavior but biology.

What drives the behavioral shift? Hormones. Belyaev's foxes showed lower cortisol levels - the stress hormone produced by adrenal glands. They also had higher serotonin, a neurotransmitter linked to calmness and social bonding. These weren't intentionally selected traits. They came along automatically with tameness, because they share a developmental pathway through neural crest cells.

In humans, the same pattern likely holds. Lower baseline aggression means altered stress response systems. This doesn't mean humans aren't aggressive - we absolutely are, particularly in proactive, calculated ways (war, competition, strategy). But our reactive aggression - impulsive, explosive violence - is markedly lower than in chimpanzees or earlier hominins.

Modern humans rarely erupt into spontaneous violence the way wild primates do. When aggression appears in humans, it's typically organized, rationalized, and culturally mediated - a fundamentally different behavioral profile from our closest relatives.

Modern humans rarely erupt into spontaneous violence the way wild primates do. We've been selected to keep our cool, negotiate, cooperate. When aggression appears, it's typically organized, rationalized, culturally mediated. That's a fundamentally different behavioral profile, likely rooted in hormonal and neural changes tied to self-domestication.

There's a flip side to neoteny: cognitive flexibility. By extending our developmental period and retaining juvenile traits, humans stay curious, playful, and open to learning far longer than other apes. Adult humans learn new skills, languages, and ideas in ways most adult animals simply can't.

Chimpanzees become set in their ways after adolescence. Their learning windows close. Humans? We keep those windows cracked open our entire lives. This "lifelong juvenility" is what allows us to adapt to radically different environments, invent new technologies, and build on previous generations' knowledge.

But there's a cost. Extended immaturity means extended dependence. Human infants are helpless for years. Our brains don't fully mature until our mid-twenties. We require massive parental investment, stable social structures, and cultural transmission of knowledge. In evolutionary terms, we traded early self-sufficiency for long-term adaptability.

It worked. Because cooperation and cumulative culture - enabled by our domesticated brains - allowed humans to dominate every terrestrial ecosystem on Earth.

Fascinatingly, self-domestication isn't unique to humans. Urban foxes living near human settlements are developing shorter snouts, smaller braincases, and reduced sexual dimorphism - classic domestication traits - without deliberate breeding. Just proximity to humans and selection against aggression (aggressive foxes get killed or driven away) is enough to trigger the process.

Among primates, bonobos offer a striking parallel. Compared to chimpanzees, bonobos are less aggressive, more playful, and more sexually diverse. They have flatter faces and smaller skulls. Some researchers argue bonobos underwent a similar self-domestication process when their populations became isolated and environmental conditions favored cooperation over conflict.

These examples suggest self-domestication isn't a one-time fluke. It's a repeatable evolutionary pathway that emerges when social selection favors tameness and cooperation.

Understanding humans as self-domesticated animals reframes debates about human nature. Are we inherently violent or peaceful? The answer is: both, depending on context. Our biology has been shaped to reduce impulsive aggression and enhance cooperation - but we retain the capacity for organized violence, particularly when directed by culture and ideology.

It also raises questions about ongoing evolution. Are we still domesticating ourselves? In densely populated, highly regulated modern societies, individuals with lower reactive aggression and higher social conformity may have reproductive advantages. Or has cultural evolution overtaken biological evolution, decoupling behavior from genetics?

"Selection against aggression has been argued to facilitate the creation of the special niche favoring the emergence of complex behaviors via cultural evolution."

- Frontiers in Psychology Editorial

Some researchers speculate about the possibility of genetic editing targeting neural crest-associated genes like BAZ1B, which influences facial morphology and behavior. Could we accelerate self-domestication intentionally? Should we? These aren't idle questions - they're ethical dilemmas for a species that has gained the power to edit its own genome.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: domestication, whether in animals or humans, involves selection against certain individuals. Dogs exist because wolves who were too aggressive didn't reproduce. Modern humans exist, in part, because our more violent ancestors were excluded from social groups, killed, or chosen against as mates.

Self-domestication isn't a gentle, egalitarian process. It's evolution through social filtering, mate choice, and yes, violence against the violent. This tension - between our image of ourselves as enlightened beings and the recognition that our prosocial nature emerged through harsh selection - is central to understanding what we are.

We are the apes who domesticated themselves by being intolerant of intolerance. We cooperated our way to dominance by excluding those who couldn't cooperate. And in doing so, we became something new: a species defined less by physical prowess than by our ability to imagine, communicate, and build shared worlds.

What happens next? In evolutionary time, humans are still very young as a domesticated species. Cultural evolution now moves far faster than biological evolution - our environments change within generations, not millennia. This creates mismatches: brains evolved for small hunter-gatherer bands now navigate megacities, digital networks, and global politics.

Some researchers suggest we're entering a phase where biology becomes increasingly optional. Gene editing, artificial intelligence, brain-computer interfaces - these technologies could reshape human nature in ways that dwarf 100,000 years of self-domestication.

Others argue our fundamental social psychology - our need for belonging, status, and meaning - will remain rooted in the psychology of a self-domesticated ape. No matter how advanced our tools, we'll still be animals shaped by selection for cooperation, gossip, and social bonding.

The truth likely lies in between. We are neither purely biological nor purely cultural beings. We're a species that evolved the capacity to reshape our own environments and, increasingly, ourselves. The self-domestication that made us human continues - but now we're aware of it. And that awareness changes everything.

Perhaps the deepest insight from self-domestication theory is this: humans didn't conquer nature through strength or speed. We succeeded by changing ourselves. By selecting for individuals who could tolerate strangers, share resources, and coordinate action, we built the foundation for everything that followed - language, culture, science, civilization.

We are, in a very real sense, designed by ourselves. Not consciously, not intentionally, but through the accumulated choices of thousands of generations about who to trust, who to follow, who to mate with. We looked at ourselves and chose the path of cooperation over domination, curiosity over certainty, culture over instinct.

In doing so, we became the juvenile apes who never stopped learning, never stopped asking why, never stopped imagining what could be. We domesticated ourselves into humanity. And the experiment is still running.

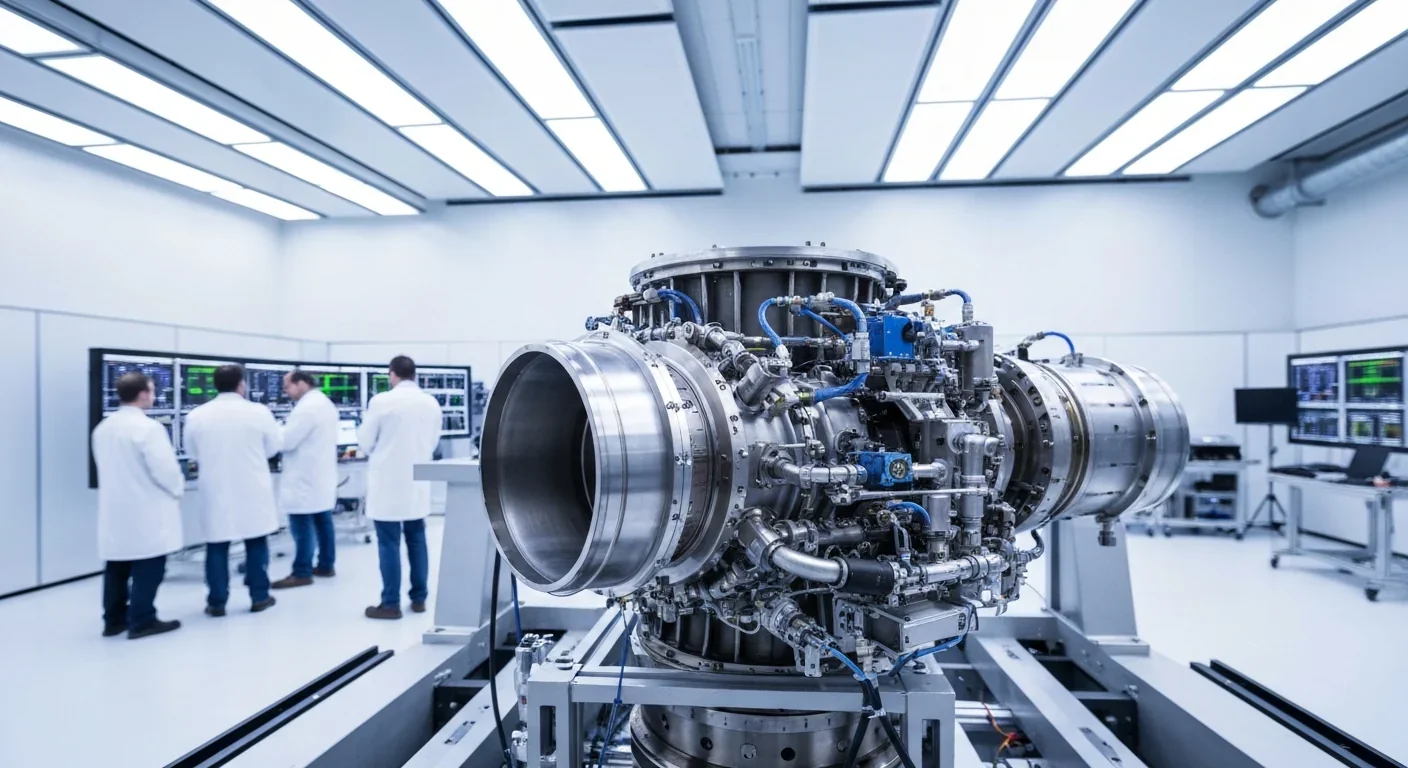

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

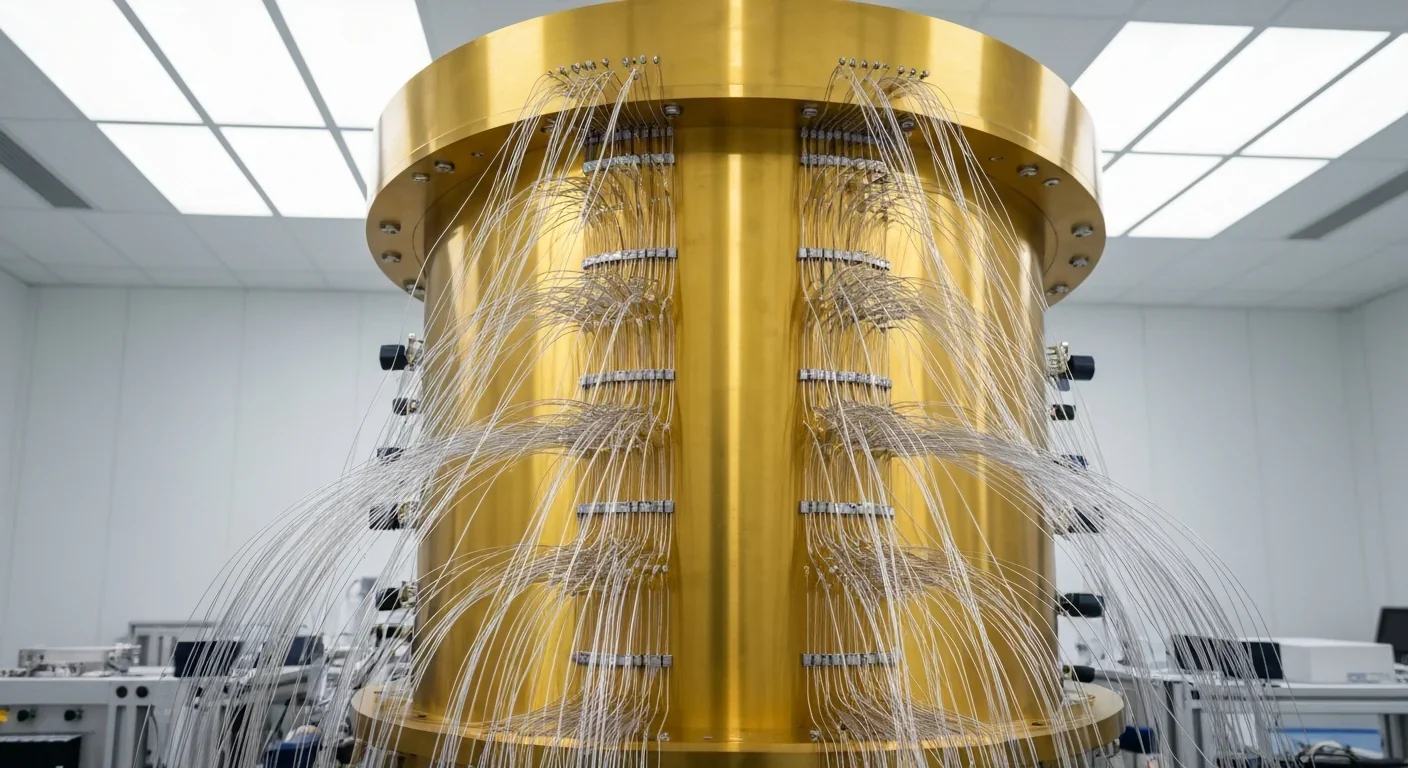

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.