The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Neuroscientists are mapping what happens in our brains during transcendent group experiences, discovering that our brain waves literally synchronize and release powerful neurochemicals like oxytocin, endorphins, and dopamine - revealing the biological basis for why humans need collective experiences.

Picture the last time you felt truly connected in a crowd - maybe at a concert where 20,000 voices merged into one, or during a protest where strangers linked arms with perfect strangers, or at a religious service where the collective prayer felt like it lifted you off your feet. That electric feeling, that sense of dissolving into something larger than yourself, isn't just in your head. Well, actually, it is - but not in the way you might think.

Neuroscientists are now mapping exactly what happens in our brains during these transcendent group experiences, and what they're finding challenges everything we thought we knew about where "you" end and "we" begin. Using cutting-edge brain imaging techniques that can scan multiple people simultaneously, researchers have discovered that when we share powerful experiences with others, our individual brain waves don't just correlate - they actually synchronize, creating patterns of neural activity that ripple across minds like a chorus of tuning forks resonating in harmony.

The implications reach far beyond explaining why concerts feel magical or why team sports create lifelong bonds. Understanding the neuroscience of collective effervescence - the term sociologist Émile Durkheim coined in 1912 for these shared transcendent states - could revolutionize how we approach mental health treatment, build more cohesive communities, design educational programs, and even understand the evolutionary forces that made us human in the first place.

When Émile Durkheim first described collective effervescence over a century ago, he was trying to explain something he'd observed in religious gatherings: people experiencing emotions together that no individual could generate alone. He noticed that when Australian Aboriginal communities performed sacred rituals, participants entered states of heightened emotion and unity that persisted long after the ceremonies ended, fundamentally reshaping social bonds and individual identities.

Durkheim believed these moments were the social glue holding civilizations together, but he had no way to peer inside participants' skulls to see what was actually happening. For decades, his concept remained purely sociological - a compelling idea without biological backing.

That changed around 2002, when neuroscientist P. Read Montague and colleagues conducted the first "hyperscanning" experiment, using fMRI to simultaneously record brain activity in two people playing a simple game together. The technology was primitive by today's standards, but it proved something crucial: you could actually measure how brains interact in real time.

Since then, the field has exploded. Researchers have developed increasingly sophisticated methods to track neural synchrony - the correlation of brain activity across multiple people. They've moved from two-person studies to examining entire groups, from tightly controlled lab experiments to naturalistic settings, from simple tasks to complex social interactions. And what they've found consistently surprises them: our brains are far more permeable to each other than anyone imagined.

When you're swept up in a powerful group experience, your brain undergoes a cascade of changes that researchers can now observe and measure with remarkable precision. It's not one system firing - it's a symphony.

First, there's the synchronization itself. Studies using EEG and fNIRS hyperscanning have shown that during coordinated activities - whether that's singing together, moving in rhythm, or even just listening to the same emotional story - specific brain regions begin firing in lockstep across different people's heads. The left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, involved in attention and cognitive control, shows particularly strong synchrony during cooperative tasks. So do areas in the temporal lobes that process social information and emotion.

This isn't just your brain responding to the same stimulus the same way everyone else's does. Researchers have cleverly ruled out that possibility by using permutation tests - essentially, they scramble the data to see if random pairings of people show the same synchrony, and they don't. The alignment only appears when people are actually interacting, actually engaged in the shared experience together.

Neural synchrony only appears when people are genuinely interacting - proof that our brains don't just process the same information similarly, they actually align with each other during shared experiences.

Then there's the neurochemical flood. Your hypothalamus starts pumping out oxytocin, the so-called "love hormone" that normally surges during intimate moments but also spikes during group bonding. Oxytocin doesn't work alone - it acts as a positive allosteric modulator of opioid receptors, which means it essentially amplifies your brain's endorphin system.

And boy, do those endorphins flow. The same β-endorphin release that gives runners their famous "high" kicks in during intense collective movement - dancing, chanting, synchronized marching. These endogenous opioids don't just block pain; they flood your brain's reward centers with feel-good signals.

Meanwhile, dopamine - which is less about happiness itself and more about anticipation and reward-seeking - surges in your nucleus accumbens, the brain's pleasure hub. Interestingly, oxytocin neurons send collaterals directly to this region, creating a feedback loop where social bonding and pleasure reinforce each other.

The result? A neurochemical cocktail powerful enough to alter your state of consciousness, temporarily dissolve your sense of individual boundaries, and create feelings of transcendence that can persist for days or even permanently reshape your worldview.

A recent study published in Frontiers in Neuroscience found that inter-brain synchrony was significantly higher when friends shared emotional stories compared to strangers doing the same task. The right superior frontal gyrus showed measurably stronger coupling in the friendship condition - quantitative proof that psychological closeness literally creates neural closeness.

Even more striking: researchers exposed participants to a pleasant odor while watching emotional movies together, and the shared sensory experience significantly amplified brain synchronization across viewers. Simple environmental cues, it turns out, can act as neural synchrony catalysts.

Our capacity for collective effervescence isn't a bug - it's a feature that's been under construction for hundreds of millions of years. The genetic roots trace back surprisingly far: oxytocin and its close relative vasopressin emerged from a single gene duplication event about 500 million years ago, long before humans walked the earth. The neural circuitry for social bonding has been conserved across vertebrate evolution, from fish to mammals.

Why? Because for our ancestors, group cohesion was literally life or death.

Imagine you're a early human 100,000 years ago on the African savanna. You can't outrun predators. You can't overpower large prey alone. Your survival depends entirely on your ability to coordinate with your tribe - to hunt together, defend together, care for each other's young. Groups that could synchronize their efforts more effectively simply outlived and outbred groups that couldn't.

But coordination isn't enough by itself. You also need motivation to stick with the group when things get hard, to sacrifice personal interest for collective good, to maintain social bonds even when they're costly. That's where collective effervescence comes in.

"Oxytocin is the neurochemical that has allowed humans to become social creatures. It is responsible for the feeling of empathy, which makes us feel closer to others by encouraging social bonding during its release."

- Khiron Clinics research summary

Those neurochemical rewards we discussed? They're evolutionary bribes. Your brain is essentially paying you in dopamine, endorphins, and oxytocin to engage in behaviors that historically improved your ancestors' survival odds. The transcendent feelings during group rituals, the euphoria of moving in synchrony, the deep satisfaction of shared purpose - these aren't meaningless side effects. They're adaptations that kept groups cohesive through generations of selection pressure.

Studies of modern hunter-gatherer societies show that groups with more frequent collective rituals - dancing, singing, storytelling around fires - demonstrate stronger social bonds, more effective resource sharing, and better child-rearing outcomes. The same patterns hold across cultures worldwide, from Amazonian tribes to Arctic communities to Pacific islanders.

Our brains, it seems, were sculpted by evolution to literally feel good about being part of something bigger than ourselves.

One of the most striking findings in this research is how universally humans seek out and create opportunities for collective effervescence, regardless of culture or historical period. The specific forms vary wildly, but the underlying pattern remains constant.

In religious contexts, it's perhaps most obvious. Pentecostal worship services with speaking in tongues, Islamic Sufi whirling dervishes, Hindu Holi festivals, Jewish Hasidic dancing, Buddhist group meditation - all deliberately orchestrate conditions that trigger collective transcendent states. The rhythmic movement, synchronized chanting, shared focus, and emotional intensity create perfect conditions for neural synchrony and neurochemical release.

But you don't need religion. Music concerts and festivals serve the same function in secular societies. Electronic dance music events, in particular, with their repetitive beats, synchronized light shows, and packed crowds moving as one, are essentially engineered for collective effervescence. The same goes for large sporting events, where tens of thousands of fans experience victory or defeat as a unified emotional entity.

Political movements tap into this too. The March on Washington in 1963, where 250,000 people gathered for civil rights, created bonds among participants that lasted lifetimes. More recently, movements like the Women's March or climate strikes produce similar effects - people report feeling transformed by the experience of marching alongside strangers toward shared purpose.

Even in work settings, collective effervescence appears. High-performing teams often describe experiencing "flow states" together, where individual effort seems to dissolve into seamless collaboration. Silicon Valley companies have tried to engineer this through open offices, team-building exercises, and company rituals, with varying degrees of success.

The common thread? All these experiences involve physical co-presence, synchronized action or attention, shared emotional intensity, and a sense of belonging to something that transcends individual identity. These are the ingredients that reliably trigger the neural and neurochemical changes underlying collective effervescence.

The implications for mental health treatment are profound and are already being explored in clinical settings.

Traditional therapy is a solitary endeavor - you and a therapist in a room. But if our brains are wired for collective experiences, might some forms of mental illness be partially caused by isolation, by lack of opportunities for collective effervescence? And might group experiences be not just supportive but actually therapeutic?

Research increasingly suggests yes. Group therapy has long been known to be effective, but we're now understanding why on a neurological level. When people share experiences - particularly emotional ones - their neural synchrony increases, which seems to enhance empathy, reduce feelings of isolation, and create stronger therapeutic alliances.

Some innovative programs are going further, deliberately engineering collective effervescence as treatment. Group drumming circles for veterans with PTSD, for instance, produce measurable reductions in symptoms that exceed what individual therapy provides. The synchronized movement, the shared rhythm, the sense of being part of a cohesive unit - these mirror the experiences that forge military bonds in the first place and may help reintegrate those neural circuits in healthier ways.

Dance therapy, particularly in group formats, shows similar promise. Moving in synchrony with others triggers endorphin release and increases oxytocin, creating natural antidepressant effects. Studies show participants report significant mood improvements that persist for days after sessions.

Even simpler interventions show effects. Choir singing, community gardening projects, group hiking - activities that combine physical co-presence, shared purpose, and coordinated action - all produce measurable mental health benefits that go beyond what you'd get from the activity alone.

Group activities that combine physical co-presence, shared purpose, and synchronized action produce mental health benefits that exceed what the same activities provide when done alone - suggesting that collective effervescence itself is therapeutic.

The mechanism seems to be that collective experiences activate multiple therapeutic pathways simultaneously: they reduce stress hormones like cortisol, increase mood-boosting neurochemicals, enhance social connection (itself a powerful predictor of mental health), and may even help repattern maladaptive neural circuits through the power of synchronized brain activity.

Beyond clinical settings, understanding collective effervescence is reshaping how we design spaces and experiences for everyday life.

In education, forward-thinking schools are moving away from purely individualized learning toward more collaborative models that leverage collective neural dynamics. When students work together on projects that require genuine collaboration - not just parallel individual work - they show enhanced learning outcomes that standard instruction can't match.

The mechanism likely involves neural synchrony increasing information transfer between brains. When students are truly engaged with each other, their synchronized brain states may facilitate a kind of "neural resonance" that makes concepts click more readily. Some researchers are exploring whether deliberately engineering conditions for collective effervescence - through movement, music, or shared intense focus - could enhance educational outcomes.

Corporate settings are catching on too, though often clumsily. The mandatory "team-building" exercises that make everyone cringe usually fail because they don't actually create the conditions for authentic collective experience - they're too forced, too artificial. But companies that figure out how to create genuine moments of collective effervescence - through meaningful shared challenges, celebrations that feel authentic, or practices that build real community - see measurable improvements in team performance, creativity, and employee retention.

Oxytocin research has shown it increases trust and cooperation, which has obvious workplace applications. Some organizations are exploring how to create environments that naturally boost oxytocin: opportunities for informal social interaction, collaborative workspaces, and practices like group exercise or meals together.

In urban planning, architects and designers are beginning to think about how to create public spaces that facilitate collective experiences. Parks designed for group activities rather than just passive recreation, community centers that host regular collective events, even traffic patterns that encourage pedestrian interaction rather than isolation in cars - all represent attempts to engineer opportunities for collective effervescence into the fabric of daily life.

The underlying insight is that humans aren't just social creatures - we're synchronously social creatures. We're built to share experiences that literally align our brains, and when modern life deprives us of those opportunities, we suffer individually and collectively.

But here's where things get uncomfortable: the same neural mechanisms that create transcendent experiences of unity and joy can also be weaponized for destructive ends.

The neurochemical rush of collective effervescence doesn't distinguish between a peaceful protest and a lynch mob, between a religious ecstasy and a nationalist rally, between team collaboration and gang violence. The same oxytocin that promotes bonding within a group can also increase aggression toward out-groups. Research shows that oxytocin makes people more protective of their in-group but can simultaneously increase prejudice and hostility toward outsiders.

History provides plenty of dark examples. Nazi rallies were explicitly designed to create collective effervescence - the synchronized chanting, the uniforms, the mass spectacles. Cult leaders from Jim Jones to Heaven's Gate understood intuitively how to engineer collective transcendent states that cemented followers' loyalty and overrode individual judgment. Extremist movements across the political spectrum use similar techniques.

"Oxytocin can increase positive attitudes, such as bonding, toward individuals classified as 'in-group' members, whereas other individuals become classified as 'out-group' members."

- Wikipedia article on Oxytocin, citing multiple experimental studies

The problem is that collective effervescence bypasses rational thought. When you're swept up in a powerful group experience, your prefrontal cortex - the brain region responsible for critical thinking and impulse control - shows reduced activity while emotional and reward centers light up. You become more susceptible to groupthink, more willing to abandon personal values for group consensus, more vulnerable to charismatic leadership.

Crowd psychology has long documented how individuals in groups can engage in behaviors they'd never consider alone - violence, rioting, persecution. We're now understanding the neural basis: the synchronized brain states and neurochemical floods that create feelings of transcendence also create vulnerability to manipulation.

Social media platforms may be inadvertently creating a kind of toxic digital collective effervescence. Echo chambers and filter bubbles create synchronized beliefs and emotions across distributed networks of people who've never physically met. The outrage cycles that characterize online discourse may trigger similar neural patterns to in-person collective experiences, with similar effects on judgment and behavior - but without the natural dampening effects of face-to-face interaction.

The challenge going forward is figuring out how to harness the positive power of collective effervescence - for healing, education, community building - while guarding against its dangers. That requires not just understanding the neuroscience but developing ethical frameworks for when and how to deliberately engineer these powerful states.

As we spend more of our lives in digital spaces, a critical question emerges: can virtual collective experiences trigger the same neural patterns as physical ones?

The answer appears to be: sort of, but not quite.

A 2025 study using EEG hyperscanning compared brain synchrony during a collaborative task performed both in virtual reality and in a real-world setting. Remarkably, inter-brain synchronization occurred at comparable levels in both conditions. When participants worked together in VR, their brains synchronized just like they did when working together in person.

This suggests that immersive virtual environments can, at least partially, replicate the neural dynamics of physical co-presence. For applications like therapy, training, or education, this is potentially revolutionary - you could create powerful collective experiences without requiring everyone to be in the same place.

But there are important caveats. Most studies finding equivalent synchrony use high-end VR systems with hand tracking, spatial audio, and other features that create genuinely immersive experiences. A Zoom call or text chat doesn't cut it - the level of immersion and interactivity matters enormously.

Moreover, even the most sophisticated VR can't yet fully replicate certain aspects of physical presence. You can't smell the crowd at a concert (though recall that odor significantly amplifies brain synchrony). You can't feel the chest-thumping bass or the body heat of hundreds of people dancing around you. You can't physically touch someone's hand or feel their embrace.

These may seem like minor details, but they likely matter. The neurochemical cocktail of collective effervescence involves multiple sensory and social inputs operating in concert. Remove too many, and you might get a pale shadow of the real thing - enough to be interesting, but not enough to produce the transformative effects we see in powerful physical collective experiences.

That said, the technology is improving rapidly. Future VR systems with haptic feedback, olfactory simulation, and even more sophisticated visual and spatial audio may close the gap. We might be on the cusp of being able to engineer powerful collective effervescence experiences entirely virtually.

The question is whether we should. Physical collective experiences require effort - you have to go somewhere, be present, coordinate with others. That effort may itself be valuable, filtering for genuine commitment and investment. If we make collective transcendence too easy, too available on demand, do we risk cheapening it? Making it manipulable in new ways?

These aren't just philosophical questions. As technology evolves, we'll need to grapple with them practically.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this field is the methodological innovation required to study something as ephemeral as collective experiences.

The core challenge: how do you bring the chaos and intensity of a music festival or political rally into a sterile laboratory while still capturing the essential phenomenon? Early studies tried using simplified tasks - tapping in rhythm, playing simple games - but questioned whether findings from such artificial settings generalized to real collective effervescence.

The solution has been dual: bring better measurement tools into the wild, and bring more realistic experiences into the lab.

Hyperscanning technology has become smaller and more portable. Modern fNIRS systems can be worn comfortably by participants engaging in natural activities - dancing, conversing, even playing sports. Wireless EEG systems make it possible to measure brain activity in crowds during real events. Researchers have scanned people at actual concerts, during group meditation sessions, at protests.

Meanwhile, lab studies have gotten more sophisticated about recreating authentic emotional experiences. Instead of bland abstract tasks, researchers use powerful films, real emotional stories, competitive or cooperative games with genuine stakes. They're finding that ecological validity - using stimuli and situations that feel real and meaningful - dramatically increases the magnitude of neural synchrony observed.

One clever approach: "pseudo-hyperscanning," where researchers scan individuals separately while they experience the same thing, then correlate their brain activity. This revealed that simply watching the same movie creates significant neural synchrony across viewers - their brains process the narrative in strikingly similar ways. When researchers added a pleasant odor to the screening, synchrony increased further, demonstrating how shared sensory cues amplify collective neural experiences.

But the gold standard remains real-time hyperscanning during genuine interaction. Studies of pairs playing music together while their brain activity is simultaneously recorded have revealed that synchrony peaks during moments of successful coordination and drops during mistakes - suggesting it's not just correlation but functionally important for actual cooperation.

Modern hyperscanning technology is portable enough to measure brain activity during real concerts, protests, and group meditation sessions - bringing the lab into the wild to capture authentic collective experiences.

Validation is crucial. Researchers use permutation tests to ensure that synchrony isn't just an artifact of similar stimuli or movement. They randomize pairings to show that the synchrony is specific to actual interacting partners. They manipulate variables like task difficulty, relationship closeness, or sensory cues to identify what drives synchrony up or down.

The result is a methodology that can quantify something that seems inherently qualitative - the feeling of being connected, of shared consciousness, of dissolving into something larger than oneself.

So where does this all lead? What happens when we fully understand the neuroscience of how humans connect?

In the near term, expect to see these insights applied more deliberately in therapeutic settings. We're likely to see growth in group-based therapies that explicitly leverage collective effervescence - not just talk therapy in a group format, but interventions involving synchronized movement, shared intense experiences, activities designed to trigger neural synchrony and neurochemical release. Early results from programs using drumming, dance, and ritual for trauma treatment are promising enough that scaled implementation seems likely within the next decade.

Education will shift too. Already, some schools are experimenting with collaborative learning environments that prioritize genuine cooperation over competition or individualized work. As the neuroscience becomes clearer about how collective experiences enhance learning, we'll likely see more intentional engineering of classroom activities to trigger beneficial neural synchrony among students.

Urban design and public policy may be next. Cities could be designed with much more attention to creating spaces and opportunities for collective experiences - not just entertainment venues, but everyday infrastructure that promotes positive collective effervescence. Public health initiatives might include community events and participatory activities as actual interventions, not just "nice-to-have" social programs.

The technology side gets wilder. As virtual reality becomes more immersive and neuroscience becomes more precise, we might reach a point where engineers can fine-tune virtual experiences to reliably produce specific neural states. Imagine VR experiences designed with perfect knowledge of how to maximize neural synchrony, optimized to trigger precise neurochemical releases, calibrated to create controlled collective effervescence on demand.

That future is both exciting and terrifying. On one hand, therapeutic applications could be revolutionary - imagine treating social anxiety, depression, or PTSD with experiences that reliably produce the healing neural patterns associated with positive collective experiences. On the other hand, the potential for manipulation is obvious. If we crack the code on reliably producing collective effervescence through technology, whoever controls that technology wields extraordinary power.

The ethical questions multiply: Do we need informed consent frameworks for activities designed to induce collective altered states? How do we prevent the weaponization of collective effervescence for political manipulation or commercial exploitation? What's the line between therapeutic intervention and mind control?

Perhaps the most profound shift will be in how we understand individual identity itself. The neuroscience of collective effervescence reveals that the boundaries between individual minds are more permeable than the Western philosophical tradition typically acknowledges. We're not discrete, independent processors of information - we're nodes in networks, constantly synchronizing with and influencing each other at the neural level.

This has implications that ripple through everything from legal responsibility (to what extent are individuals accountable for actions taken while swept up in collective states?) to political philosophy (how do we balance individual autonomy with our deep-seated need for collective experiences?) to spirituality (were mystics who described experiencing oneness with others or the universe actually describing neural synchrony?).

We're at the beginning of understanding how human brains connect, but already the implications are staggering. The science of collective effervescence isn't just explaining why concerts feel magical or why rituals persist across cultures - it's revealing fundamental truths about what it means to be human, about the neurological substrate of society itself.

As we decode the brain's "shared high," we're really decoding the biological basis of human civilization, discovering the neural machinery that allowed our ancestors to form communities, create cultures, and eventually build the complex interconnected world we inhabit today. And we're learning how to consciously shape that machinery, for better or worse, as we move into a future where the line between individual and collective consciousness grows increasingly blurred.

The question isn't whether we'll use this knowledge - we already are. The question is whether we'll use it wisely, preserving the transcendent power of genuine human connection while guarding against its darker applications. That answer won't come from neuroscience alone. It'll require wisdom, ethics, and collective deliberation about the kind of world we want to create.

Fittingly, it'll require exactly the kind of collective experience we've been studying - humans coming together to synchronize not just their brain waves, but their values and vision for the future.

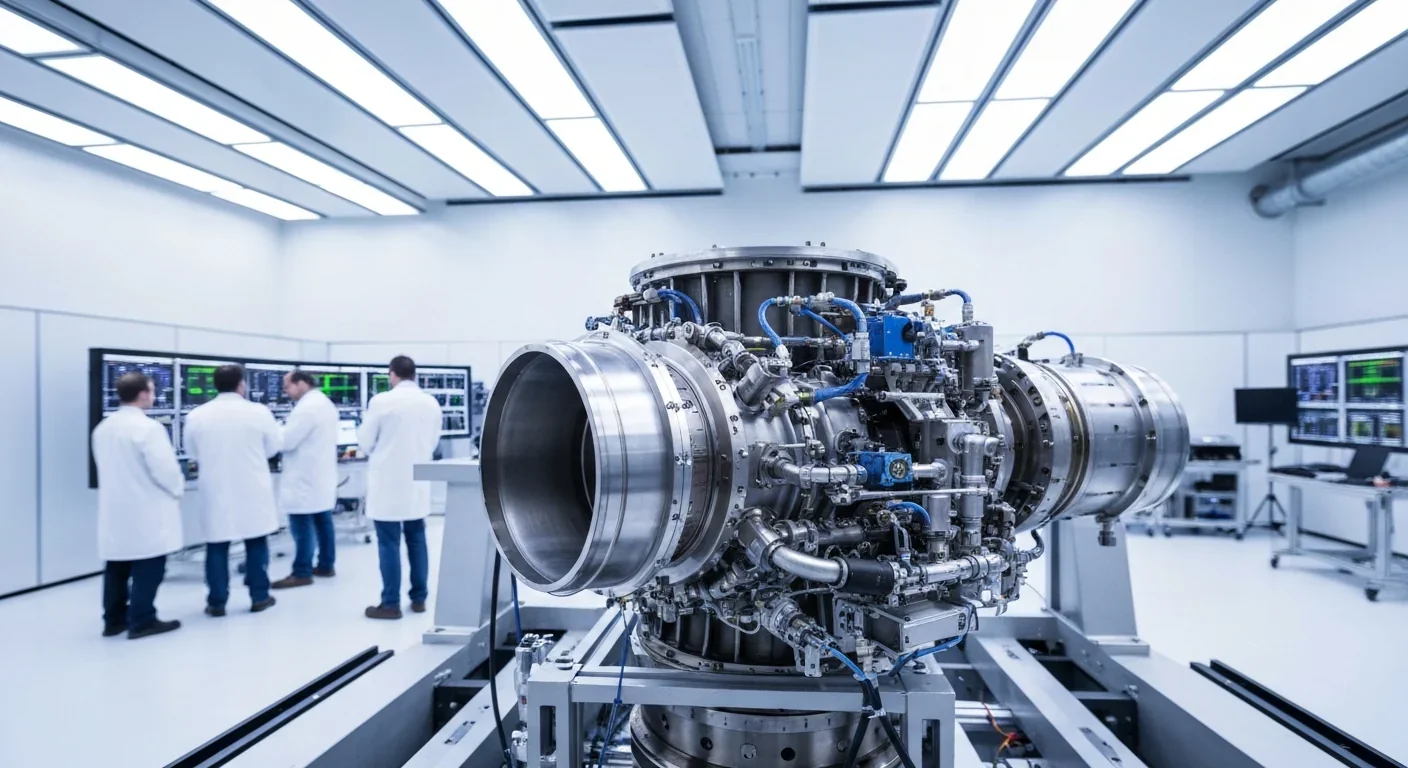

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

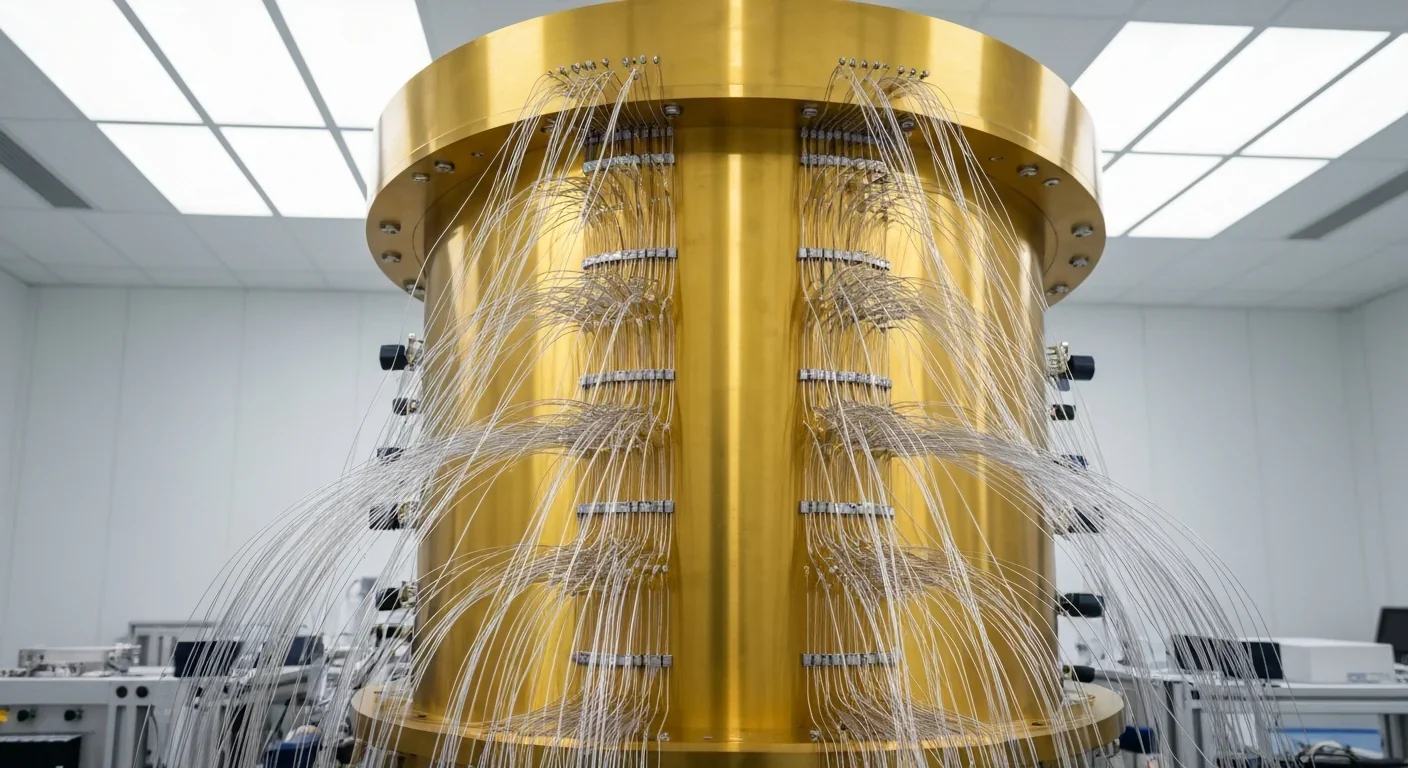

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.