The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: New research shows parenting differences between mothers and fathers are far more flexible than evolutionary theory once suggested. While biology creates initial tendencies, neuroplasticity enables both parents to develop caregiving capabilities through experience, challenging traditional gender-based parenting assumptions.

In the next decade, understanding why parents behave differently won't just be academic - it'll reshape workplace policies, family court decisions, and how we support all types of families. New brain imaging studies show that becoming a father literally rewires the male brain, while evolutionary theory explains why these changes happen in the first place. But here's the twist: the science reveals that parenting differences aren't as fixed as we once thought.

Back in 1972, evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers published a theory that would change how we understand family dynamics forever. His parental investment theory proposed a simple but powerful idea: the parent who invests more time and energy into offspring becomes a limiting reproductive resource, making them choosier about mates and more invested in caregiving.

The theory emerged from observations across animal species. In mammals, females typically carry and nurse offspring, investing months or years per child. Males could theoretically reproduce more frequently with less biological investment per offspring. This asymmetry, Trivers argued, created different evolutionary pressures that shaped parenting behaviors we still see today.

But half a century later, modern neuroscience and social research are revealing a far more nuanced picture - one where biology creates tendencies, not destinies.

The original logic of parental investment theory starts with reproductive biology. In humans, pregnancy lasts nine months, followed by months of energy-intensive breastfeeding. A mother investing this much becomes extraordinarily valuable to offspring survival, creating evolutionary pressure for maternal behaviors focused on infant care.

Fathers face different pressures. Without the certainty mothers have about genetic parenthood, evolutionary theory predicted that paternal investment would be more variable - higher when paternity confidence is strong, lower when it's uncertain. This led to predictions about mate guarding, resource provision, and protection rather than direct infant care.

Hunter-gatherer societies seemed to confirm this split. Men typically hunted large game and defended territory while women gathered plant foods and cared for young children. The sexual division of labor appeared universal across cultures, suggesting deep evolutionary roots.

Human fathers show remarkably high parental investment compared to males of most mammalian species - many actively participate in daily caregiving and experience neurobiological changes that support nurturing behaviors.

Yet this traditional picture misses something crucial: human fathers show remarkably high parental investment compared to males of most mammalian species. Men don't just provide resources - many actively participate in daily caregiving, form deep emotional bonds with children, and experience neurobiological changes that support nurturing behaviors.

The question isn't whether evolution shaped parental behaviors. It's whether those evolutionary influences are flexible enough to adapt to modern family structures.

The most striking recent discoveries come from brain imaging studies. When researchers at USC scanned first-time fathers before and after their babies were born, they found something remarkable: new dads lost about 1% of their gray matter volume across the transition to parenthood.

Before you panic, this isn't brain damage - it's neural remodeling. Similar changes occur in new mothers, where brain volume loss correlates with stronger maternal attachment. The pruning likely reflects neural specialization, where the brain becomes more efficient at processing infant-related information.

Here's where it gets interesting: the fathers who lost the most gray matter showed the strongest caregiving behaviors. They spent more time with their infants, felt more bonded, took more pleasure in interaction, and experienced less parenting stress. Brain changes weren't obstacles to caregiving - they were adaptations that supported it.

"The very same changes linked with fathers' greater investment in caregiving also seemed to heighten their risk of sleep trouble and mental health problems."

- Dr. Darby Saxbe, USC Research Team

But there's a cost. Those same brain changes correlated with worse sleep and higher rates of depression and anxiety at six and twelve months postpartum. The neurobiological transformation that makes fathers better caregivers also makes them more vulnerable to mental health challenges.

This dual nature reveals something important: the "paternal brain" isn't fundamentally different from the maternal brain. Both undergo similar remodeling processes in response to caregiving demands. The differences aren't about capacity - they're about how biology, hormones, and social expectations interact.

The endocrine system plays a starring role in parenting behaviors. Oxytocin, often called the "bonding hormone," surges during childbirth and breastfeeding in mothers, but it also increases in fathers who engage in caregiving. Studies show that when dads hold, play with, or comfort their babies, their oxytocin levels rise just like mothers.

Testosterone tells a more complex story. Across cultures, men's testosterone levels drop significantly after becoming fathers, with the biggest decreases in men who spend the most time in direct childcare. Lower testosterone correlates with more nurturing behaviors and less risk-taking - adaptations that prioritize infant safety.

But this hormonal shift isn't automatic. Research on California mice, one of the few mammal species where males provide extensive paternal care, shows that pups raised by involved fathers have different hormonal profiles themselves. Paternal care creates intergenerational effects through epigenetic changes - the way genes are expressed without changing the DNA sequence itself.

In humans, this means caregiving behaviors can reshape not just the parent's biology, but potentially influence how the next generation parents. The implications are profound: if parenting styles partly arise from being parented, then changes in family structures could compound across generations.

If parental behaviors were purely biological, we'd expect them to be universal. They're not. Parenting practices vary dramatically across cultures, revealing how social context shapes evolutionary tendencies.

In many Western societies, mothers spend significantly more time in direct childcare than fathers, even when both parents work full-time. Time-use studies show that mothers still do about twice as much childcare as fathers in two-parent households. This disparity seems to confirm traditional gender roles.

But elsewhere the pattern differs. Among the Aka people of Central Africa, fathers hold infants for several hours daily and participate actively in all aspects of care except breastfeeding. Aka fathers show some of the highest paternal involvement rates documented in any human society - levels that would seem "maternal" by Western standards.

When policies and norms support father involvement, men step into caregiving roles. When employment practices penalize paternal leave-taking, they don't - revealing how social arrangements shape what looks like "natural" behavior.

The Scandinavian countries provide another illuminating case. With generous parental leave policies that encourage father participation, paternal caregiving rates have increased substantially over recent decades. Swedish fathers take an average of three months of parental leave, and studies show this early involvement predicts continued engagement in childcare years later.

Cultural research demonstrates that what looks like "natural" gendered parenting often reflects social arrangements more than biological imperatives. When policies and norms support father involvement, men step into caregiving roles. When employment practices penalize paternal leave-taking, they don't.

This creates what researchers call "maternal gatekeeping" - situations where mothers, consciously or unconsciously, control fathers' access to and participation in childcare. Traditional gender role attitudes strengthen this gatekeeping, creating a feedback loop where expectations limit opportunities which then confirms the expectations.

If parental investment theory depends on sex differences in reproductive biology, what happens in same-sex parent families? This question is more than academic - it tests whether the theory's predictions about mother-father differences rely on essential gender differences or simply reflect the division of reproductive labor.

The research is remarkably consistent: children raised by same-sex parents show comparable developmental outcomes to those raised by different-sex parents on measures of psychological adjustment, academic achievement, and social functioning. This finding challenges any simple biological determinism about parenting requirements.

In same-sex couples, caregiving tasks get divided, but not along traditional gender lines. Studies show that same-sex parents tend to share childcare more equally than different-sex couples, possibly because they can't fall back on cultural scripts about mothers and fathers. Instead, they negotiate divisions of labor based on work schedules, individual preferences, and practical considerations.

Interestingly, same-sex parents report similar neurobiological changes to different-sex parents. The primary caregiving parent - regardless of gender - shows brain changes, hormonal shifts, and behavioral patterns similar to what's typically seen in mothers. The less involved parent shows patterns more typical of traditional fathers. Biology doesn't determine who takes which role, but it does respond to whoever provides primary care.

"The capacity for nurturing exists in both sexes - it's the activation that varies based on circumstance, not the underlying biological potential."

- Contemporary Parenting Research

The existence and success of same-sex families demonstrates that parental investment theory's core insight - that caregiving requires investment of time and energy - remains valid even when the sex-based assumptions break down. Both adults in any couple can develop the neural and hormonal changes that support nurturing. The question is which one does, not which one can.

Single-parent families and families with stay-at-home fathers add further evidence. When fathers become primary caregivers, they develop caregiving skills and emotional bonds indistinguishable from those typically associated with mothers. The capacity exists in both sexes - it's the activation that varies based on circumstance.

So where does this leave parental investment theory? The framework remains useful for understanding the evolutionary origins of parental behaviors, but it requires significant updates for modern application.

The evidence suggests a model where evolution created potential for flexible caregiving behaviors in both sexes rather than rigidly sex-typed programs. Pregnancy and lactation create initial asymmetries that influence but don't determine long-term caregiving patterns. Neurobiological systems for nurturing exist in all humans, activated by caregiving experience rather than sex alone.

This explains several puzzles. It accounts for why paternal involvement varies so dramatically across cultures while maternal involvement remains relatively consistent - mothers everywhere nurse infants, creating baseline involvement, while father involvement depends more on social structure. It explains why fathers can develop maternal-like caregiving patterns when circumstances require it. And it reconciles evolutionary theory with the reality of diverse modern families.

But flexibility cuts both ways. If caregiving capacity exists in both parents, then unequal divisions of labor reflect choices and constraints more than necessities. This shifts responsibility: policies that make father involvement difficult aren't just respecting biological realities - they're actively preventing men from developing capabilities they possess.

Workplace cultures that penalize paternal leave, child custody arrangements that assume mothers are natural primary parents, and social expectations that men should prioritize career over family - all these structures shape parental behavior in ways that may amplify small biological tendencies into large behavioral differences.

Understanding parental investment theory's insights and limitations has real-world applications. For expectant parents, recognizing that father involvement requires intentional cultivation - not just natural instinct - changes preparation. The data suggests fathers should start caregiving tasks immediately after birth, since early involvement predicts long-term engagement and triggers helpful neural changes.

For employers and policymakers, the research supports generous parental leave for all parents. When fathers take substantial leave, they bond with infants and develop caregiving skills during the critical early months. Countries with use-it-or-lose-it paternal leave see higher takeup rates than those with transferable leave, suggesting policy design matters enormously.

For family courts, the science challenges presumptions that mothers are naturally better suited for primary custody. While pregnancy and nursing create early asymmetries, long-term caregiving capacity depends on who has been providing care, not on sex. Judges evaluating custody arrangements should focus on actual caregiving history rather than gendered assumptions.

Current postpartum mental health screening focuses overwhelmingly on mothers, missing struggling fathers who may be experiencing neurobiological changes that affect their wellbeing just as profoundly.

For mental health providers, recognizing that paternal neural changes carry risks as well as benefits suggests the need for better postpartum screening for fathers. The same brain remodeling that supports caregiving also increases vulnerability to depression and anxiety. Current screening focuses overwhelmingly on maternal mental health, missing struggling fathers who may be experiencing neurobiological changes that affect their wellbeing.

For advocates of non-traditional families, the research provides evidence that what matters is committed caregiving, not the sex or number of parents. Children need adults who invest time, energy, and emotional resources - the specific family structure matters less than the quality of care provided.

Several frontiers remain unexplored. Most brain imaging studies of parental neural changes have focused on cisgender different-sex couples. We need research on same-sex couples, single parents, transgender parents, and families using assisted reproduction to understand how caregiving behaviors emerge across diverse family structures.

The intergenerational transmission of parenting behaviors deserves more attention. If caregiving experiences reshape biology in ways that affect the next generation, then large-scale shifts in family structures could have compounding effects over time. Societies moving toward more shared parenting might see subsequent generations where both sexes find caregiving easier.

The interaction of social policy and biology offers another rich area. Natural experiments like Scandinavian parental leave expansions or the rapid increase in remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic create opportunities to study how changes in opportunity affect caregiving behaviors and whether biological responses follow.

Gene-environment interactions remain poorly understood. While we know caregiving triggers neural and hormonal changes, we don't know why some individuals show stronger responses than others or whether genetic variation influences caregiving capacity and flexibility.

Parental investment theory gave us a lens for understanding the evolutionary origins of family dynamics. Half a century later, that lens needs adjustment. Biology creates potential and tendencies, but humans show remarkable flexibility in actualizing those potentials.

The takeaway isn't that parental differences don't exist or don't matter. It's that they're far more malleable than traditional readings of evolutionary theory suggested. Mothers and fathers can parent differently while both being capable of the full range of caregiving behaviors. Culture and policy shape which behaviors emerge.

For modern families, this is liberating. It means there's no single correct way to divide caregiving, no natural arrangement that must be followed. Same-sex couples, single parents, stay-at-home dads, co-parenting arrangements - all can provide excellent care when they align with parents' circumstances and preferences rather than fighting biological imperatives that turn out to be less imperative than we thought.

The science shows that becoming a parent changes your brain, your hormones, and your behavior regardless of your sex. What matters most isn't whether you're a mother or father, but whether you're present, engaged, and supported in doing the hardest and most important work any of us will do. Evolution gave us the capacity for caregiving. The rest is up to us.

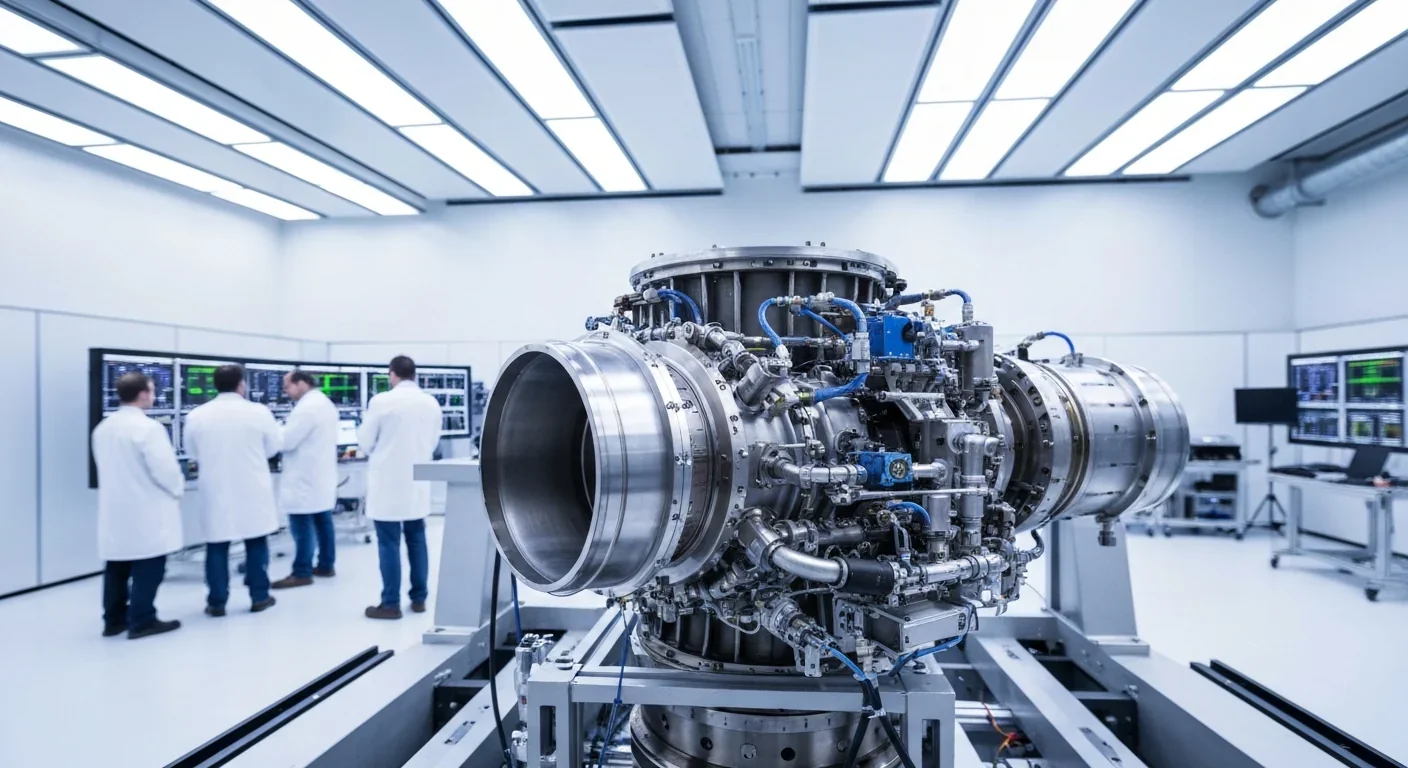

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

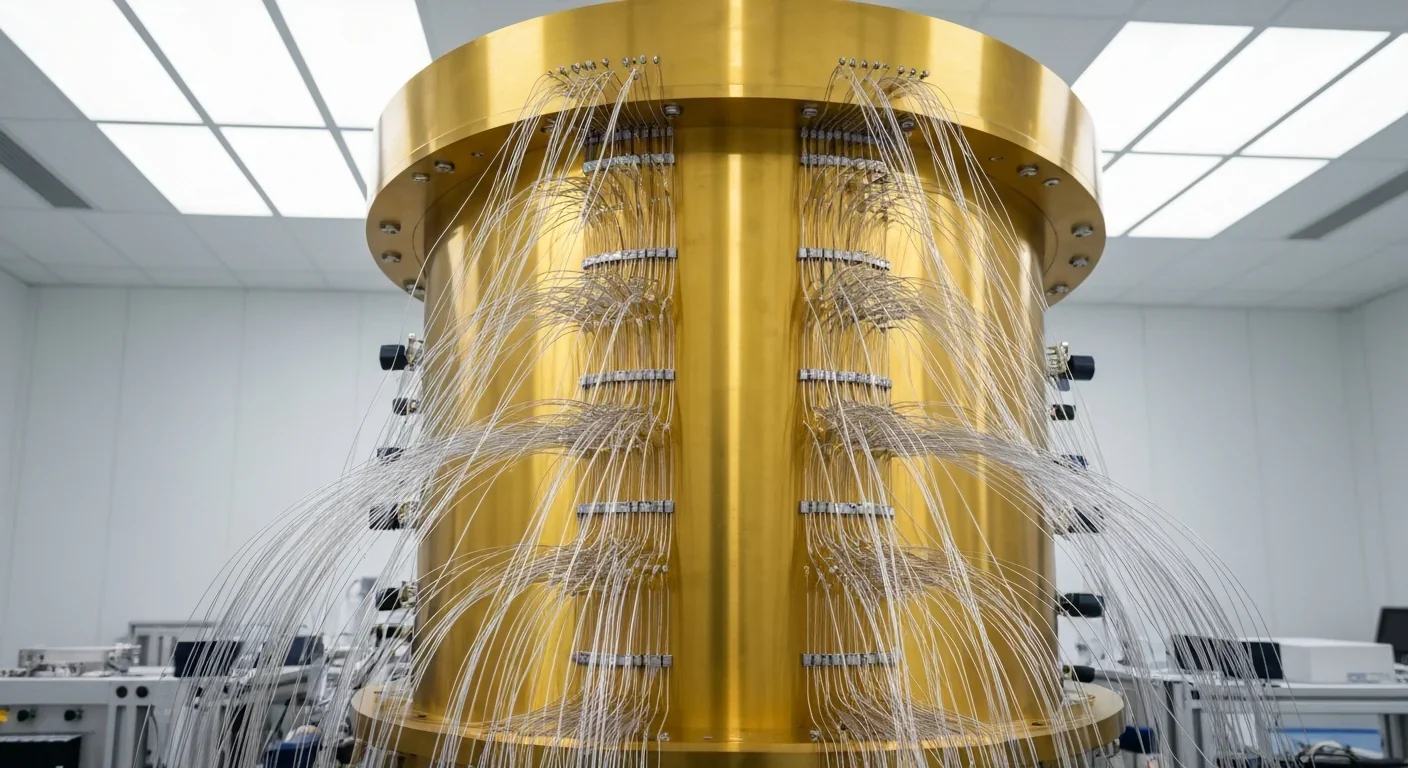

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.