Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Unconscious transference - when witnesses misidentify innocent people as criminals due to memory confusion - is the leading cause of wrongful convictions. New neuroscience reveals how our brains create false associations between familiar faces and crimes, while evidence-based reforms like double-blind lineups and jury education could prevent these devastating errors.

By 2030, advances in neuroscience and artificial intelligence could finally solve one of criminal justice's most persistent nightmares: the innocent person convicted because a witness's brain confused a familiar face with a criminal's. This phenomenon, called unconscious transference, has destroyed countless lives. Ronald Cotton spent 11 years in prison for rapes he didn't commit because the victim's memory betrayed both of them. Her confidence was absolute. Her identification was wrong. And the psychological mechanism behind this error affects every one of us.

Unconscious transference is a memory error where eyewitnesses misidentify an innocent but familiar person as the perpetrator of a crime. You might have seen someone at the grocery store, the gym, or walking past your house. Weeks later, when you're shown a police lineup, your brain sends a recognition signal. But it can't retrieve the context. Your memory says "I know this face" without remembering where or when. Under stress and pressure to identify the criminal, witnesses make a logical but catastrophic inference: the familiar person must be the one who committed the crime.

Research shows this isn't simple confusion. When people view a mugshot paired with questions like "which person did you see committing this act?" their brains create a specific association between that face and the queried action. The connection forms automatically, outside conscious awareness. Younger adults construct detailed action-person links, while older adults experience a more general feeling of familiarity lacking source information. Both mechanisms lead to the same outcome: false identification.

Approximately 75% of DNA exonerations involved mistaken eyewitness identification - making it the leading cause of wrongful convictions in America.

The statistics are chilling. Approximately 75% of DNA exonerations involved mistaken eyewitness identification. Since the 1990s, DNA testing has freed hundreds of innocent people who served years in prison, some on death row, because eyewitnesses confidently identified the wrong person. Eyewitness misidentification isn't a rare glitch. It's the leading cause of wrongful convictions in the United States.

In 1984, Jennifer Thompson was raped in her Burlington, North Carolina apartment. During the attack, she made a deliberate effort to study her assailant's features so she could identify him later. She told herself: remember his face, remember everything, so you can make sure he's caught.

Days later, police showed Thompson a photo lineup. She identified Ronald Cotton. At trial, she pointed at him with absolute certainty. "I am sure this is the man," she testified. The jury believed her. Cotton received life in prison.

But Thompson had seen Cotton before, though neither realized it. He worked near her neighborhood. Her brain had stored his face as familiar. Under the trauma and stress of the attack, her memory reconstructed events, filling gaps with the most familiar face available. The real rapist, Bobby Poole, wasn't someone she'd seen before the attack.

Eleven years later, DNA evidence proved Cotton's innocence and identified Poole as the actual perpetrator. Thompson and Cotton eventually became friends and advocates for reform, working together to prevent others from experiencing the same tragedy.

"I am sure this is the man."

- Jennifer Thompson's testimony that sent an innocent man to prison for 11 years

Thompson's misidentification wasn't willful or reckless. Her confidence was genuine. That's what makes unconscious transference so dangerous and so difficult for legal systems to address. The witness believes what they're saying. Their certainty feels real because, to their reconstructed memory, it is real.

Memory doesn't work like a video recorder. It's reconstructive, not reproductive. During a traumatic event, your brain primarily absorbs the gist of what's happening along with fragments of detail. Later, when you try to recall the event, your brain fills gaps unconsciously through inference, expectation, and information encountered after the event.

The process creates what psychologists call "false recollection." Research by Alan Kersten and Julie Earles found that viewing a mugshot while answering questions about specific actions leads eyewitnesses to form associations between the person and those actions, even when the person never performed them. This happens both immediately and after delays of several weeks. The false memory persists and often grows stronger over time.

Elisabeth Loftus's pioneering research demonstrated how easily memory changes through misinformation. In her famous studies, changing a single word in a question altered what people remembered seeing. Participants who heard the word "smashed" instead of "hit" were more likely to falsely remember seeing broken glass that never existed. If memory is that malleable with minor wording changes, imagine the impact of suggestive police procedures, leading questions, and the stress of witnessing or surviving a crime.

The brain's fusiform face area processes facial recognition through specialized neural networks. When you see a familiar face, activity increases in the fusiform gyrus and amygdala. The N250 brain signal, which responds more strongly to familiar faces, activates regardless of whether you can consciously recall where you know the person from. Your brain recognizes the face before your conscious mind can place it in context. This neural response creates the feeling of familiarity that witnesses mistake for identification of the perpetrator.

Understanding why innocent people get identified as criminals requires examining how the brain processes faces, stores memories, and responds to stress. Brain imaging studies reveal that the same neural patterns activate whether someone correctly identifies a known person or falsely identifies a stranger as familiar. The medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus and surrounding structures, plays a crucial role in memory formation and retrieval. But this system is vulnerable to confusion, especially when stress, trauma, and time pressure interfere with normal processing.

During traumatic events, stress hormones affect memory encoding. The amygdala, which processes emotional responses, determines what gets attention and what gets encoded into memory. High stress can either enhance memory for central details or impair it, depending on various factors. The "weapon focus effect" is a well-documented example: when a weapon is present, witnesses tend to focus attention on the weapon rather than the perpetrator's face, reducing accurate facial encoding.

Your brain recognizes familiar faces before your conscious mind can place them in context - creating the dangerous illusion that familiarity equals identification.

Age also affects susceptibility to unconscious transference. Research comparing younger adults (median age around 19) with older adults (median age around 71) found different mechanisms at work. Younger adults form specific action-person associations during mugshot viewing. Older adults rely on a general feeling of familiarity without source details. Both pathways lead to misidentification, but through different cognitive processes.

The cross-race effect adds another layer of complexity. People are significantly better at recognizing faces from their own racial or ethnic group compared to other groups. This isn't evidence of prejudice but rather a result of differential experience and perceptual learning. The implications for criminal justice are serious, especially in cases like Ronald Cotton's, where cross-race identification increased the risk of error.

Beyond Ronald Cotton, numerous documented cases illustrate unconscious transference in action. The phenomenon isn't theoretical - it's destroyed real lives and continues to pose risks every day.

Change blindness research provides experimental evidence of how easily people miss identity changes. In studies where the perpetrator's identity changed midway through a video of a burglary, 61% of participants didn't notice the switch. They confidently identified one of the two people they'd seen, often choosing whichever seemed more familiar or fit their expectations. This demonstrates that even when watching a recorded event, people don't encode facial details as completely as they believe.

The legal system has been slow to recognize these problems. Until recently, most courts treated eyewitness confidence as a reliable indicator of accuracy. But research consistently shows confidence and accuracy are poorly correlated, especially when identification occurs weeks or months after the crime. Worse, witness confidence often increases over time, even for false memories, as the brain reinforces the reconstructed narrative through repeated retrieval.

Expert testimony on memory fallibility has become increasingly accepted in courts, but many jurisdictions still don't permit it. Law enforcement often lacks training in memory science. Judges may not understand how memory works or fails. The result is a criminal justice system built on a flawed foundation: the assumption that confident eyewitnesses can be trusted.

The legal system's traditional reliance on eyewitness testimony made sense in an era before DNA testing revealed how often these identifications go wrong. Now, with hundreds of DNA exonerations providing irrefutable evidence of the problem's scope, the question isn't whether reform is needed but how quickly and completely it can be implemented.

Several evidence-based reforms have emerged from decades of psychological research. Double-blind sequential lineups represent a significant improvement over traditional simultaneous lineups. In a double-blind procedure, the officer administering the lineup doesn't know which person is the suspect, preventing unconscious cues that might influence the witness. Sequential presentation, where witnesses view one person at a time rather than all at once, reduces the tendency to make relative judgments ("who looks most like the perpetrator?") in favor of absolute judgments ("is this the person I saw?").

"False recollection is really troubling from a legal perspective because this type of memory leads an eyewitness to put a face to a context of a crime scene, incorrectly linking the two together."

- Dr. Julie Earles, researcher on eyewitness memory

Proper jury instructions can help jurors understand memory's limitations. Research shows that when jurors learn about factors affecting eyewitness accuracy - cross-race effects, weapon focus, confidence inflation, unconscious transference - they make more discerning judgments. They're less likely to convict solely on eyewitness identification and more likely to seek corroborating evidence.

The cognitive interview protocol has raised correct identification rates from approximately 60% to 80% in controlled studies. This structured approach helps witnesses retrieve memories without suggestion or contamination. It involves asking open-ended questions, encouraging detailed free recall before asking specific questions, and avoiding leading prompts that might create false associations.

State-level reforms have gained momentum. Indiana recently passed its first comprehensive eyewitness identification reform bill. Massachusetts updated its jury instructions. New York courts have applied heightened scrutiny to eyewitness evidence in several 2024 decisions. These changes signal growing recognition that procedural reforms can reduce wrongful convictions without undermining legitimate prosecutions.

The gap between scientific knowledge and legal practice remains frustratingly wide. We've known about unconscious transference and its mechanisms for decades. Yet many jurisdictions still use identification procedures that psychological research has shown to be unreliable.

Context-breaking instructions represent a simple but effective intervention. Before viewing a lineup, witnesses are told explicitly that the familiar person they might recognize and the criminal are not the same person. This instruction disrupts the unconscious inference process. Studies demonstrate it can eliminate unconscious transference effects by preventing the witness from assuming familiarity equals guilt.

Recording confidence statements immediately after identification, before any feedback, provides crucial evidence about reliability. Witness confidence often increases after receiving feedback ("yes, that's the suspect" or "you picked the same person the other witness chose"). This confidence inflation misleads juries who hear the inflated confidence at trial rather than the witness's original certainty level.

Computer-assisted lineup systems can standardize procedures and eliminate administrator influence. These systems present photos sequentially, record exact timestamps of responses, and capture confidence statements before any feedback. They ensure consistent implementation of evidence-based practices across different cases and jurisdictions.

Other countries have grappled with these same issues, some implementing reforms earlier than the United States. The United Kingdom revised its identification procedures following several high-profile wrongful convictions in the 1970s and 1980s. Canadian courts have long been more receptive to expert testimony on eyewitness reliability than American courts.

Countries that have adopted comprehensive eyewitness reforms maintain effective prosecution rates while dramatically reducing wrongful convictions.

Australia's legal system has incorporated memory science into judicial training and jury instructions more systematically than most U.S. jurisdictions. The cross-national differences highlight that reform is possible when political will and scientific evidence align. Countries that have adopted comprehensive reforms report maintaining effective prosecution rates while reducing wrongful convictions.

International collaboration among researchers, legal professionals, and policy makers accelerates progress. The Innocence Project and similar organizations worldwide share best practices, successful reform strategies, and lessons learned from implementation challenges. This global perspective reveals that unconscious transference isn't culturally specific - it's a universal feature of how human memory works.

Even if you're never called as a witness or face criminal charges, understanding unconscious transference matters. It reveals fundamental truths about how your brain constructs reality. The confident feeling that you "know" something isn't always reliable. Your memory isn't a factual record but a reconstructed narrative, vulnerable to suggestion, stress, and time.

This knowledge should foster epistemic humility. When you're certain you remember something accurately, consider that certainty might be a product of reconstruction rather than objective recall. When you hear about eyewitness testimony in trials, recognize that the witness's confidence doesn't guarantee accuracy. When you serve on a jury, demand corroborating evidence beyond identification alone.

For parents, educators, and anyone who interacts with the legal system, awareness of these mechanisms is protective. If you or someone you know becomes a crime victim or witness, understanding how to preserve memory accuracy matters. Write down details immediately, before discussing the event with others. Avoid viewing photos or information about suspects before official identification procedures. Request double-blind sequential lineups and cognitive interviews. These practices protect both the innocent and the quest for justice.

Looking ahead, technology offers both promise and peril. Facial recognition AI systems could theoretically reduce reliance on fallible human memory. But these systems carry their own biases and error rates, particularly for people of color and women. AI doesn't solve the underlying problem if it simply automates the same mistakes human witnesses make.

More promising are neuroscientific tools that might assess memory reliability in real-time. Research using fMRI to examine patterns of brain activity during identification could potentially flag cases where unconscious transference is likely. Imagine a future where neural markers predict which witnesses are at high risk for false identification, allowing extra procedural safeguards for those cases.

Virtual reality and augmented reality might revolutionize lineup procedures. Instead of static photos, witnesses could view three-dimensional representations from multiple angles, potentially improving discrimination between similar faces. VR could also enhance training for law enforcement, allowing officers to experience firsthand how easily memory errors occur.

But technology alone won't fix the problem. The solution requires cultural change within law enforcement, judicial education, legislative reform, and public understanding. It requires admitting that for decades, we've imprisoned innocent people based on a misplaced faith in memory's accuracy. That admission is uncomfortable. It's also necessary.

Ronald Cotton and Jennifer Thompson's story illustrates both the tragedy of unconscious transference and the possibility of redemption. Cotton lost 11 years of his life. Thompson lives with knowing her certain identification was catastrophically wrong. Yet together, they've channeled that pain into advocacy that's changing how the justice system handles eyewitness evidence.

Their message is clear: good people, acting in good faith, can destroy innocent lives when procedures don't account for memory's reconstructive nature. Witnesses aren't lying when they make false identifications. Jurors aren't negligent when they believe confident eyewitnesses. The problem is systemic, rooted in outdated assumptions about how memory works.

The science is clear. The solutions exist. Implementing them requires political will, resources, and a willingness to acknowledge past mistakes. States that have adopted reforms demonstrate it's possible to protect both public safety and individual rights. The question isn't whether we can fix these problems - it's whether we'll prioritize doing so.

Every day that passes without comprehensive reform means more risk of wrongful convictions, more innocent people in prison, more actual perpetrators remaining free. The neuroscience of unconscious transference doesn't just explain how memory errors occur. It provides a roadmap for preventing them. We have the knowledge. Now we need the will to use it.

The hidden memory trap that turns innocent bystanders into criminals isn't inevitable. It's fixable. The only question is how many more Ronald Cottons and Jennifer Thompsons will experience this nightmare before we finally fix it.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

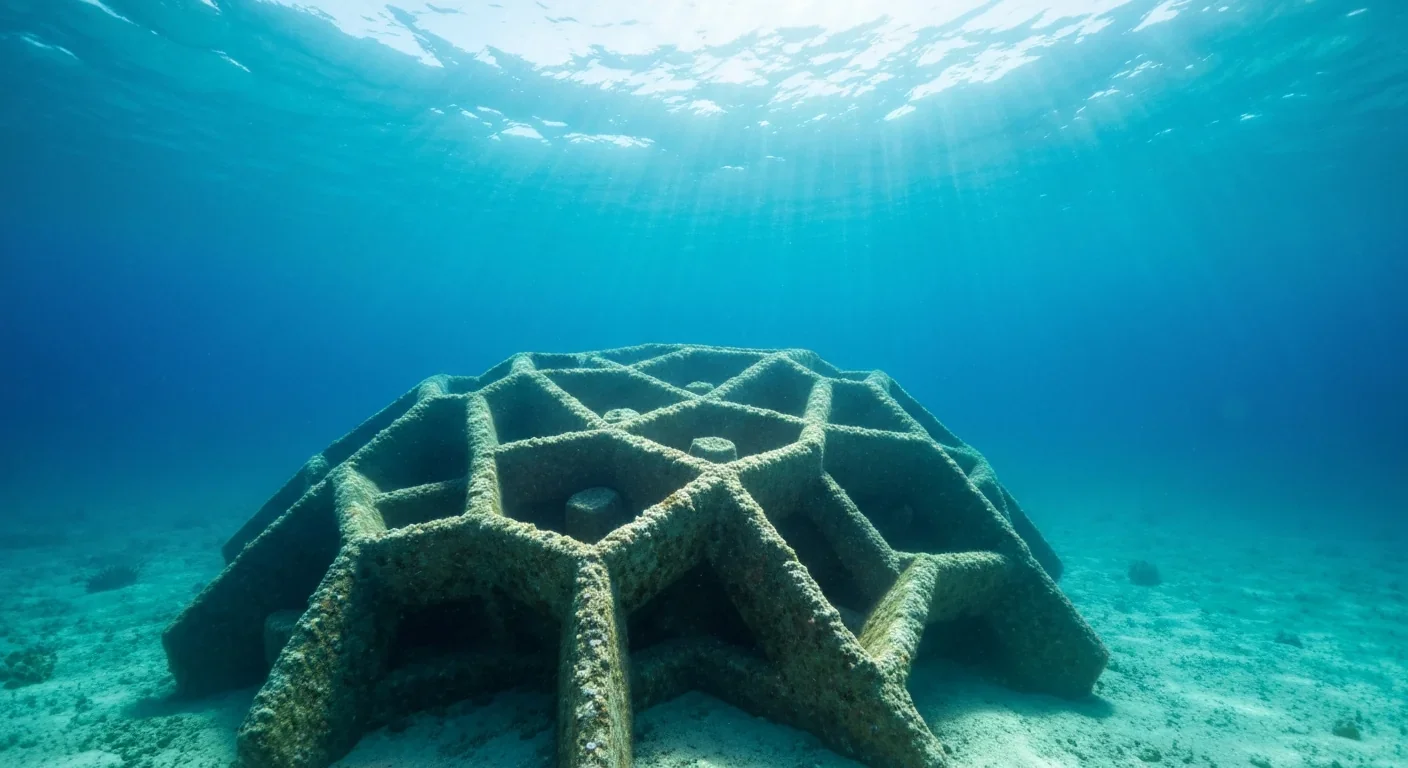

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

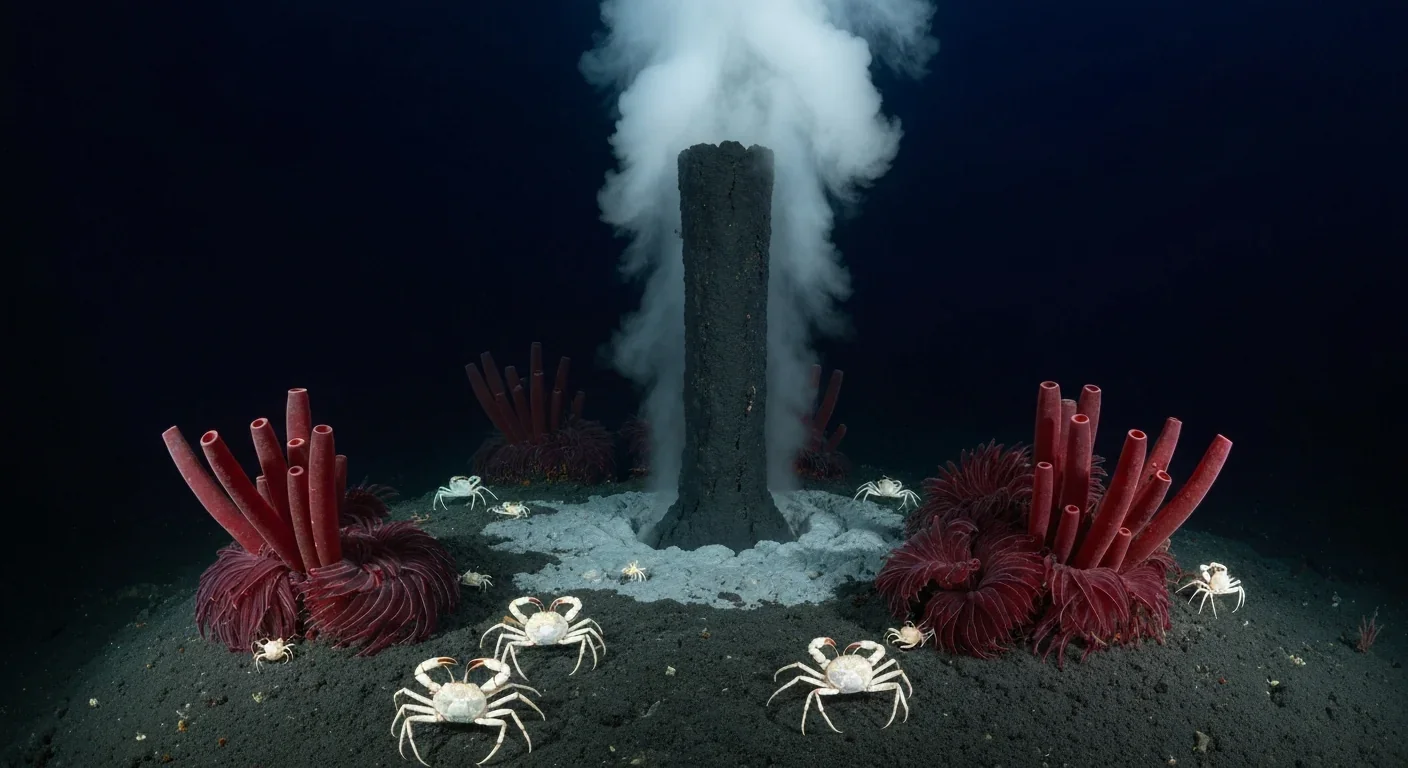

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

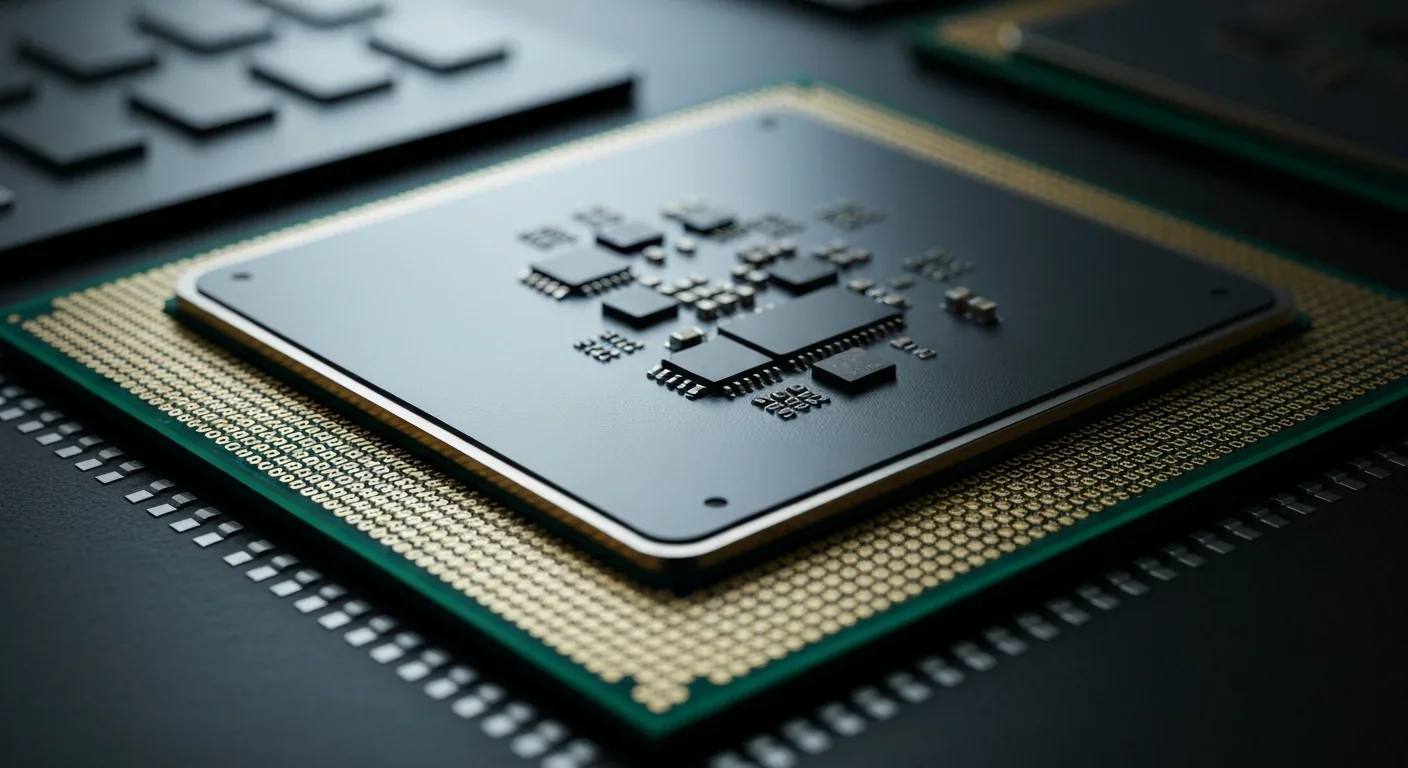

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.