The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Your brain is hardwired to remember information about you better than anything else. The self-reference effect - a cognitive phenomenon backed by decades of research - shows that linking new information to your personal experiences dramatically improves memory retention, offering practical applications for students, professionals, and lifelong learners.

What if I told you that the most powerful memory tool you possess isn't a fancy app, a color-coded notebook system, or even hours of repetition? It's something you carry everywhere: yourself. Your brain has a built-in favoritism for anything connected to you, and once you understand this quirk, you can exploit it to remember almost anything.

Welcome to the self-reference effect - a cognitive phenomenon that's been quietly revolutionizing how we think about learning, memory, and the very architecture of human consciousness.

In 1977, psychologists Timothy Rogers, Nicholas Kuiper, and W.S. Kirker stumbled onto something remarkable. They asked participants to process words in different ways - some judged whether words were printed in capital letters, others decided if words rhymed, and still others considered whether words described them personally.

Later, when asked to recall the words, participants remembered the self-related ones far better than any others. Not just a little better - significantly better. It wasn't even close.

This wasn't a fluke. Decades of subsequent research confirmed that when you link information to yourself, your brain treats it like VIP content. A 1997 meta-analysis by Symons and Johnson reviewing dozens of studies found the effect holds up across ages, cultures, and types of information.

The implication? Your sense of self isn't just who you are - it's how you learn.

Think about the last time someone mentioned your name in a crowded room. You heard it immediately, right? Even though dozens of other words were being spoken. Your brain has dedicated neural real estate for processing self-related information, and it's prime property.

Neuroimaging studies consistently show that when you process information about yourself, specific brain regions light up like a Christmas tree. The star of the show is the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), a region sitting right behind your forehead that acts as the brain's "self-processing hub."

But the mPFC doesn't work alone. Recent research published in the Journal of Neuroscience revealed something even more intricate: a network connecting the mPFC to another region called the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex (Pcu/PCC). When you encode information about yourself, this network becomes hyperactive, strengthening the memory trace.

Here's where it gets really interesting. The study found that people with higher ratios of excitatory neurotransmitters (glutamate) to inhibitory ones (GABA) in these regions showed even stronger self-reference effects. In other words, your brain's chemical balance literally determines how much you benefit from thinking about yourself.

So why does self-reference work so well? Two complementary theories explain the advantage.

The elaboration hypothesis suggests that relating information to yourself forces deeper processing. When you ask "Does this describe me?" you're not just passively reading - you're actively connecting the new information to your vast store of self-knowledge: your experiences, your goals, your quirks, your failures and triumphs. Each connection creates a web of associations, and the more connections you make, the easier it is to retrieve the memory later.

Think of it like this: if memory is a library, self-reference doesn't just file a book - it cross-references it with hundreds of other books you've already read.

The organizational hypothesis adds another layer. According to research by Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker, self-referential encoding encourages clustering and organization during recall. Your self-concept is one of the most organized knowledge structures in your brain. When you tie new information to this structure, you're essentially sorting it into a pre-existing, well-organized filing system.

It's not just that you process the information more deeply - you also store it more systematically.

"The self-reference effect refers to people's tendency to better remember information when that information has been linked to the self than when it has not been linked to the self."

- Psychology Research Encyclopedia

The self-reference effect isn't just for young, healthy brains. It persists across the lifespan, though with some fascinating variations.

Research shows that older adults - who often struggle with memory tasks - still benefit substantially from self-referential encoding. In fact, self-reference can sometimes help older adults perform as well as younger people on memory tests. The technique seems to compensate for age-related cognitive decline by tapping into deeply ingrained self-knowledge that remains intact even as other cognitive systems falter.

Children also show the effect, though it develops as their sense of self matures. By adolescence, the self-reference advantage is fully operational, suggesting that as your self-concept becomes more elaborate and stable, it becomes an even more powerful learning tool.

Even clinical populations benefit. Interestingly, people with depression show altered patterns - they remember negative self-related information better than positive, reflecting their negative self-schemas. This tells us something profound: the self-reference effect doesn't just enhance memory; it reveals the emotional coloring of how we see ourselves.

Enough theory. How do you actually use this in real life?

Stop passively reading your textbooks. Instead, constantly ask: "How does this relate to me? When have I experienced something like this? How would I explain this to a friend?"

Let's say you're studying the concept of cognitive dissonance - the discomfort you feel when your actions contradict your beliefs. Don't just memorize the definition. Think about the last time you experienced it. Maybe you value environmental sustainability but drove to work instead of biking because it was raining. That discomfort? That's cognitive dissonance. Now you'll never forget it.

Research by Hartlep and Forsyth (2001) and others shows that students who use self-referential encoding during exam preparation demonstrate significantly better recall compared to those who use standard study techniques.

Learning a new software system at work? Don't just follow the tutorial. Think about how you'll use each feature in your specific projects. Relate new skills to problems you've already solved.

Trying to remember client names? Link them to personal associations. "Janet reminds me of my aunt Janet who always wears bright colors." It sounds trivial, but these personal connections create powerful memory anchors.

Instead of memorizing vocabulary lists in isolation, build sentences about yourself. Learning Spanish? Don't just memorize "perro" means "dog." Say "Tengo un perro negro" (I have a black dog) - even if you don't have a dog, the act of connecting the word to a personal statement strengthens the memory.

Educational research shows that when students find material personally relevant, not only does their memory improve, but their intrinsic motivation increases. It's a double win.

Trying to remember where you parked? Instead of just noting "Level 3, Section B," tell yourself a story: "I parked on Level 3 because that's how many cups of coffee I had today, and Section B for 'Bad parking job.'" Silly? Yes. Effective? Absolutely.

The self-reference effect is powerful, but it's not magic. There are situations where it's weaker or doesn't help much.

When self-awareness is low: If you're distracted, stressed, or intoxicated, your ability to engage in self-referential encoding diminishes. You can't link information to yourself if you're barely aware of yourself in the moment.

For purely procedural knowledge: The self-reference effect works best for conceptual information - facts, ideas, principles. It's less helpful for pure motor skills. You can't think your way to a better golf swing just by relating it to yourself; you need practice.

When the information genuinely doesn't relate to you: Some facts resist personal connection. The atomic number of tungsten? The capital of Uzbekistan? Unless you're a chemist who loves Tashkent, forcing a self-connection can feel contrived and may not help.

That said, even seemingly arbitrary facts can sometimes benefit from creative self-linking. The key is making the connection meaningful and genuine rather than forced.

The self-reference effect works best when you create authentic, meaningful connections between new information and your actual experiences, goals, or identity.

How does self-reference stack up against other popular memory strategies?

Versus repetition: Repeating information works through sheer exposure, but it's inefficient. Self-reference achieves deeper encoding with less effort. Quality beats quantity.

Versus the method of loci: The ancient technique of associating information with locations in a mental "memory palace" is powerful and often outperforms simple self-reference for lists or sequences. However, it requires upfront investment to build and maintain your mental palace. Self-reference is instant - your self-concept is always available.

Versus elaborative interrogation: This technique - asking yourself "why" questions about facts - creates connections similar to self-reference. The difference? Self-reference grounds those connections in the most accessible knowledge base you have: your own life.

Versus spaced repetition: Spaced repetition optimizes the timing of review sessions to fight forgetting. It's highly effective, especially for long-term retention. Here's the thing: you can combine it with self-reference. Relate information to yourself and review it at optimal intervals. The two strategies complement each other beautifully.

Recent advances in brain imaging have uncovered even more sophisticated mechanisms underlying the self-reference effect.

A 2025 study in the Journal of Neuroscience used both fMRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure brain activity and neurochemistry simultaneously. The researchers found that people with higher glutamate-to-GABA ratios in the precuneus showed stronger activation in this region during self-referential encoding - and better memory afterward.

More remarkably, the study revealed that connectivity between the precuneus and medial prefrontal cortex predicted both neurochemical balance and the magnitude of the self-reference effect on memory. This suggests a neurochemical-network-behavioral pathway: your brain chemistry influences network connectivity, which in turn determines how much you benefit from self-reference.

This opens intriguing possibilities. Could we one day enhance learning by temporarily modulating these neurochemical systems? Some research has explored transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the medial prefrontal cortex, though initial results suggest the effects are complex and don't simply "boost" the self-reference effect. Still, understanding the neurochemical basis might eventually lead to targeted interventions.

The self-reference effect raises profound questions about the nature of selfhood. If your sense of self is so central to how you process and remember the world, then strengthening your self-concept might be one of the most important things you can do for your cognitive health.

This has implications for education, therapy, and personal development. Students with clearer, more positive self-concepts may be better positioned to leverage self-referential encoding. Therapeutic interventions that help people develop healthier self-narratives might simultaneously enhance their cognitive functioning.

There's also a social dimension. Recent research explores the "group reference effect" - we also show enhanced memory for information related to our social groups and identities. Your self doesn't exist in isolation; it's woven into your relationships, communities, and cultures. Understanding how we remember through these collective identities could transform how we teach history, foster empathy, and build stronger communities.

"When students find the material personally relevant, not only does their memory improve, but their intrinsic motivation to engage with the material also increases."

- Brain2Heart Educational Research

Where is this field headed? Several frontiers look particularly promising.

Personalized learning systems: Imagine educational software that automatically relates new concepts to your personal experiences, interests, and goals. As AI systems learn more about individual learners, they could craft explanations specifically designed to trigger your self-reference effect.

Therapeutic applications: Since people with depression show biased self-referential memory (remembering negative information better), interventions that rebalance self-referential processing might help treat mood disorders. Cognitive bias modification training already shows some promise.

Developmental research: We still don't fully understand how the self-reference effect emerges in childhood and how it changes across the lifespan. Researchers are calling for more studies on adolescent populations, a critical period when identity formation is in full swing.

Cross-cultural studies: Most self-reference research has been conducted in Western, individualistic cultures. Do people in collectivist cultures, where the self is defined more relationally, show different patterns? Some evidence suggests they might, but this remains an open question.

Neurochemical interventions: As we better understand the glutamate-GABA balance underlying self-referential memory, we might develop targeted interventions - whether pharmacological, neurostimulation-based, or even dietary - that optimize this balance.

Here's the beautiful thing about the self-reference effect: you can start using it immediately. You don't need special equipment, software, or training.

The next time you need to remember something - a name, a concept, a procedure - pause for a moment and ask: "How does this relate to me? When might I use this? How does it connect to something I've experienced?"

That simple question transforms passive reception into active, personalized encoding. You're not just storing information; you're weaving it into the fabric of who you are.

Your brain already wants to remember things about you. All you have to do is give it the chance.

And here's the twist: the more you practice self-referential thinking, the richer your self-concept becomes. Each time you connect new information to yourself, you're not just improving memory - you're expanding your sense of who you are. Learning becomes self-discovery. Memory becomes identity.

So go ahead. Make it personal. Make it yours. Your brain will thank you.

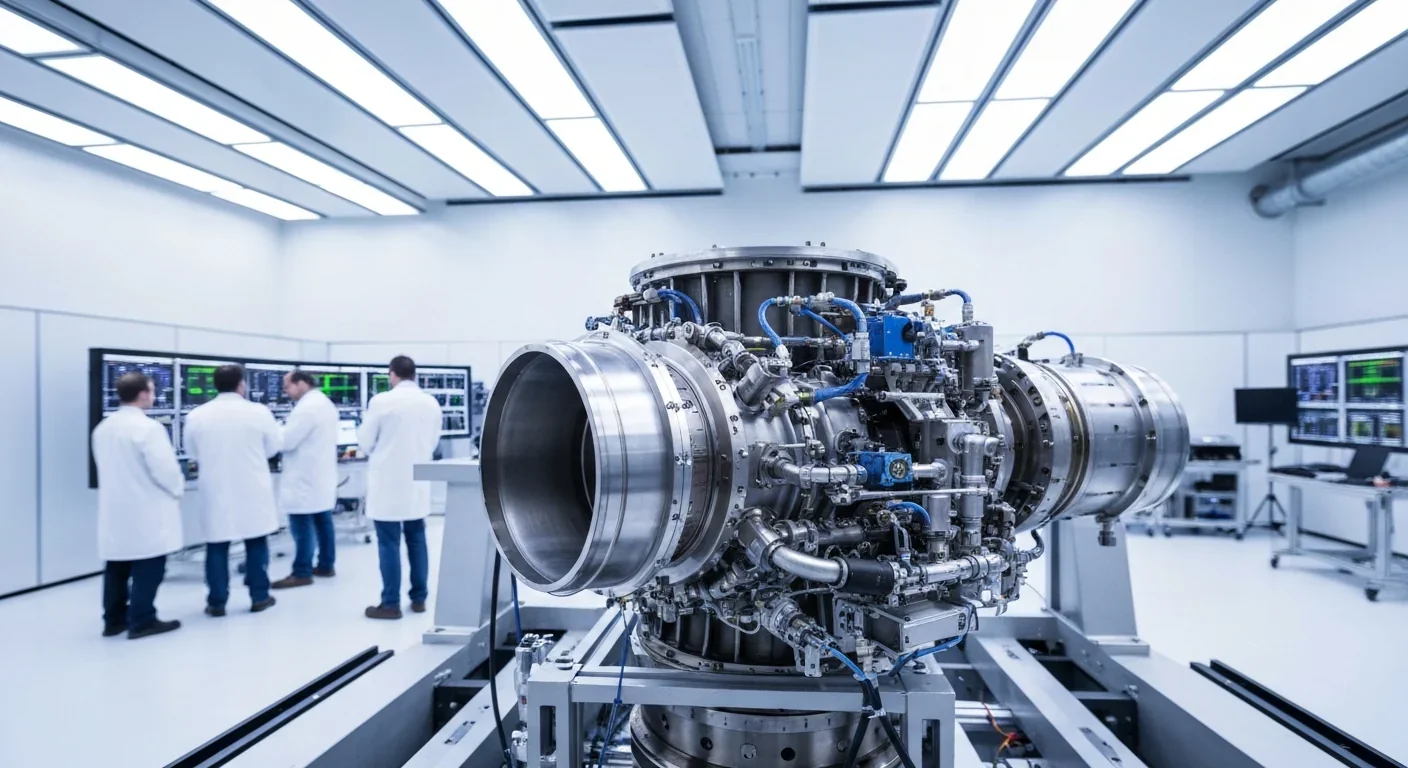

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

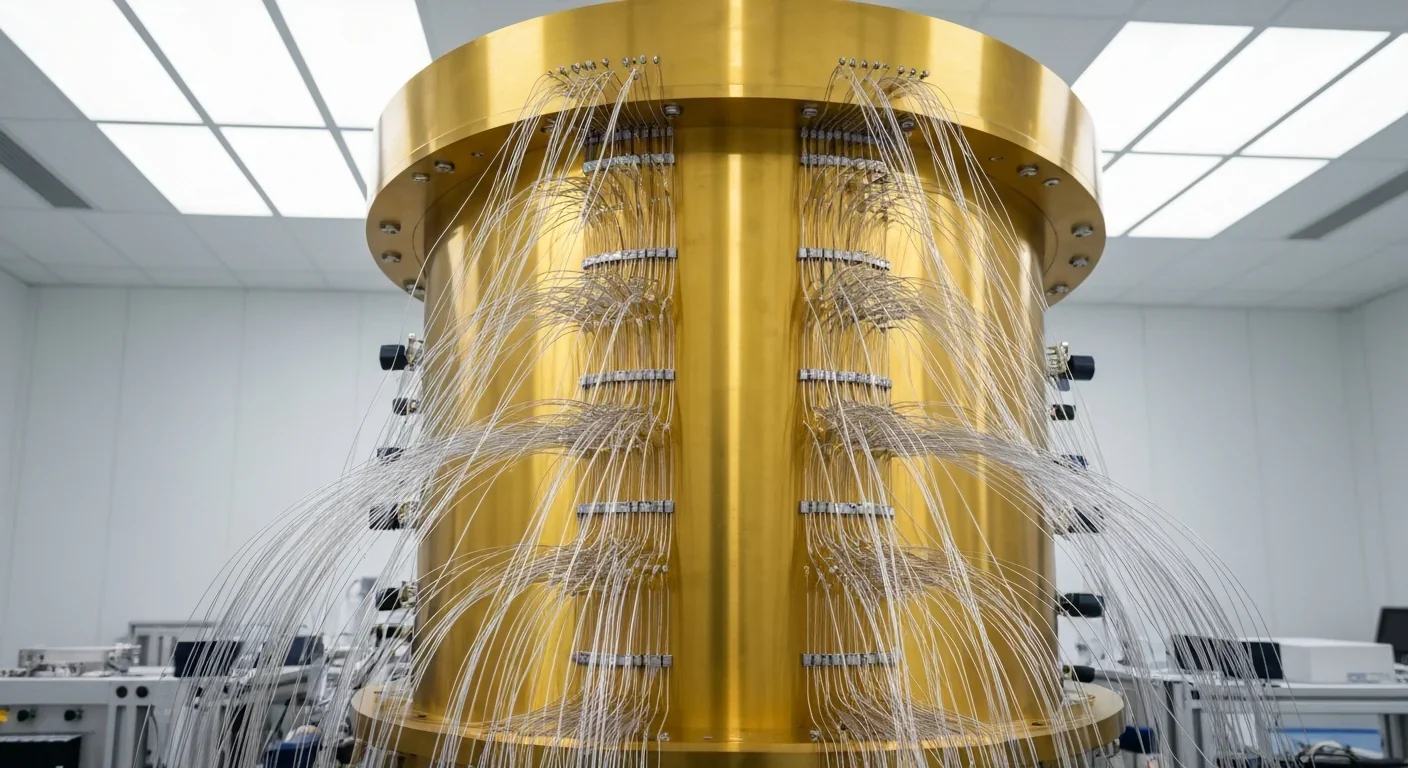

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.