The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Working memory holds about four chunks for 30 seconds - a biological limit that determines teaching success. Cognitive load theory reveals why traditional methods fail and offers evidence-based strategies that can double learning outcomes.

Within the next decade, every classroom in the world will need to reckon with a stubborn biological fact: human working memory can juggle only about four chunks of new information at once. This isn't a problem technology can solve or a limitation we can train away. It's the architecture of the human mind, and it's forcing a revolution in how we design learning experiences.

For decades, cognitive scientists have known that working memory acts as a bottleneck for all learning. Now, as education moves online, as AI tutors proliferate, and as the volume of information students must process explodes, that bottleneck is becoming impossible to ignore. Teachers who understand cognitive load theory can design lessons that work with the brain's constraints. Those who don't risk overwhelming their students, no matter how passionate or knowledgeable they are.

The implications stretch far beyond classrooms. Corporate trainers, online course creators, app designers - anyone building learning experiences - faces the same fundamental challenge: how do you transfer knowledge into minds that can only hold a few pieces of information at once?

In 1988, Australian educational psychologist John Sweller published a theory that would reshape instructional design: cognitive load theory. Sweller wasn't interested in abstract debates about learning styles or philosophy. He wanted to understand why some teaching methods worked and others failed, based on how the brain actually processes information.

His insight was deceptively simple. Learning happens when information moves from working memory into long-term memory, where it gets organized into complex knowledge structures called schemas. But working memory is astonishingly limited. While your long-term memory can store essentially unlimited information, your working memory can handle only about four chunks of new information simultaneously.

This overturned earlier assumptions. In 1956, psychologist George Miller had published his famous paper "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two," suggesting working memory could hold five to nine items. For decades, educators designed around that number. But modern research revealed the true capacity is closer to four, and even that depends on how information is structured.

Sweller realized that if you overwhelm working memory, learning grinds to a halt. Students might look engaged, might be working hard, might even feel like they're learning - but if their working memory is overloaded, nothing transfers to long-term storage. The effort is wasted.

Working memory can hold only about four chunks of information for roughly 30 seconds. If you overwhelm it, learning stops - no matter how hard students try.

Consider how math is often taught. A teacher presents a new type of problem, explains the solution method, then immediately asks students to solve similar problems on their own. This seems logical: practice makes perfect, right?

Wrong, according to cognitive load theory. Novice learners trying to solve problems must simultaneously figure out the goal, recall relevant principles, consider multiple solution paths, and execute calculations. Each element demands working memory space. For a beginner, this is like trying to juggle while learning to juggle - the cognitive load is crushing.

The worked-example effect demonstrates a better approach. When students study fully worked examples before attempting problems themselves, they learn faster and retain more. Why? Because examining a completed solution requires less working memory than generating one from scratch. Students can focus on understanding the solution structure rather than struggling with execution.

This finding contradicted decades of educational practice. Many teachers believed students learned by discovering solutions themselves, by struggling productively. And there's truth to that - but only for students who already have sufficient background knowledge. For novices, unguided problem-solving creates so much cognitive load that little learning occurs.

The split-attention effect reveals another common mistake. Imagine a geometry lesson where students must look at a diagram on one page, then read instructions on another, constantly switching back and forth. This seems like a minor inconvenience. But every time students shift attention, they must reconstruct their mental model. Working memory gets consumed by integration rather than learning.

Integrating text and diagrams, using spoken explanations alongside visuals, removing unnecessary decorative elements - these aren't aesthetic choices. They're interventions that free up working memory for actual learning.

Cognitive load theory distinguishes three types of mental burden, and understanding them is crucial for effective teaching.

Intrinsic load comes from the material's inherent complexity. Teaching calculus carries higher intrinsic load than teaching addition. You can't eliminate intrinsic load - it's the actual content students need to learn - but you can manage it by breaking complex topics into simpler parts and teaching prerequisite knowledge first.

Extraneous load is the pointless burden created by poor instructional design. Fancy PowerPoint transitions, cluttered slides, unclear instructions, requiring students to flip between materials - these add zero educational value while consuming precious working memory. Most teaching improvements come from ruthlessly eliminating extraneous load.

Germane load is the productive effort of building schemas and transferring information to long-term memory. This is the load you want. Good instruction minimizes extraneous load and manages intrinsic load so students can devote maximum working memory to germane processing.

Think of working memory as a four-slot inventory in a video game. Every piece of information occupies a slot. If three slots are filled with distractions and poor design (extraneous load), you have only one slot left for actual learning. Eliminate the junk, and suddenly you have four slots available.

"The goal isn't to eliminate all mental effort - it's to eliminate the wrong kinds. Good instruction minimizes extraneous load so students can focus on germane processing."

- Core principle of Cognitive Load Theory

Here's where cognitive load theory gets interesting: the same lesson that works perfectly for novices can actually harm expert learners. This is called the expertise reversal effect.

Remember worked examples? Fantastic for beginners, but experts find them boring and inefficient. Why? Because experts have already automated the solution process. Their schemas are so well-developed that worked examples force them to process information they've already mastered, creating unnecessary cognitive load.

This explains why differentiated instruction matters so much. A teaching strategy isn't good or bad in absolute terms - it's good or bad for students at specific expertise levels. The challenge is that most classrooms contain students at multiple levels simultaneously.

Expert teachers develop an intuitive sense of cognitive load. They notice when students' eyes glaze over, when confusion spreads across faces, when the class goes suddenly quiet. These are signs of cognitive overload. The best teachers respond by simplifying, removing distractions, breaking complex ideas into smaller pieces, or providing worked examples.

But intuition isn't enough. Research shows that teachers often misjudge cognitive load, underestimating how difficult material is for genuine novices. We all suffer from the curse of knowledge - once you understand something, it's almost impossible to remember what it was like not to understand it.

As education moves online, cognitive load theory becomes even more critical. Digital environments can reduce cognitive load - or explode it catastrophically.

Consider online video lectures. In principle, they're perfect for managing cognitive load. Students can pause, rewind, and rewatch difficult sections. They can control the pace. Yet many online courses fail spectacularly because designers ignore basic cognitive load principles.

A typical mistake: video lectures with the instructor's face in one corner, slides in the middle, a chat window on the side, and notifications popping up. Each element demands attention. Students must decide where to look, integrate multiple information streams, and filter out distractions. Working memory fills up with interface management rather than content.

The modality effect offers a solution. When you present visual information (diagrams, equations, demonstrations) with spoken explanation rather than written text, you effectively expand working memory capacity. Why? Because the brain processes visual and auditory information through partially separate channels. It's not that you have more slots - you're using different mental resources.

But digital environments also create new opportunities. Adaptive learning systems can adjust difficulty based on student performance, automatically managing intrinsic load. Well-designed educational software can eliminate split-attention effects by perfectly integrating text and images. Spaced repetition algorithms can optimize the transfer from working to long-term memory.

The technology is neutral. What matters is whether designers understand cognitive architecture.

Not everyone accepts cognitive load theory. Critics raise legitimate questions.

Some researchers argue that the theory oversimplifies learning, particularly for creative and complex domains. They point out that struggling with difficult problems - even when it creates high cognitive load - can promote deeper understanding and transfer.

Others question whether we can accurately measure cognitive load in real classrooms. Most research uses artificial laboratory tasks. Measuring the cognitive load of learning poetry or discussing history involves subjective judgment.

There's also debate about whether minimizing cognitive load is always desirable. Productive struggle matters. Students need to develop persistence, learn to manage frustration, and build metacognitive skills. If we always optimize for minimal cognitive load, do we produce learners who can't handle difficulty?

These criticisms have merit. Cognitive load theory describes important constraints, but it's not a complete theory of learning. Motivation matters. Social interaction matters. Cultural context matters. Emotion and identity matter.

The theory works best for teaching well-structured domains with clear right answers: mathematics, physics, computer programming, language grammar. It offers less guidance for teaching critical thinking, creativity, or navigating ambiguous real-world problems.

Yet even critics acknowledge that understanding working memory limits improves instruction. You can recognize cognitive load theory's value while avoiding dogmatic application.

Critics rightly note that cognitive load theory isn't the whole story - motivation, social context, and productive struggle all matter. But understanding working memory constraints still improves teaching across all domains.

Decades of studies have identified specific strategies that reliably reduce cognitive load and improve learning:

Worked examples and faded guidance. Start with complete worked examples, then gradually remove steps until students solve problems independently. This scaffolding matches support to developing expertise.

Integrated materials. Place explanatory text directly on diagrams rather than in separate captions. Use spoken narration for visual demonstrations.

Segmenting complex information. Break lengthy lessons into short, focused segments with pauses for processing.

Removing redundancy. Don't present the same information in multiple formats simultaneously. Reading identical text while listening to narration doubles the load without adding value.

Using concrete examples. Abstract principles consume more working memory than concrete instances. Teach general rules through specific examples rather than starting with abstractions.

Building on prior knowledge. New information connects to existing schemas, reducing cognitive load. That's why analogies and connections to familiar concepts work so well.

Interleaving practice. Mixing different types of problems, rather than blocking practice by type, creates desirable difficulty that improves long-term retention without overwhelming working memory.

The effect sizes are substantial. Meta-analyses show well-designed worked examples can produce effect sizes above 0.7 - meaning the average student in a cognitive load-optimized classroom outperforms 75% of students in traditional instruction.

Understanding schemas reveals why practice matters so much. When you first learn to drive, every action demands conscious attention: checking mirrors, signaling, steering, monitoring speed. Your working memory is maxed out just keeping the car on the road.

With practice, these skills become automated. You don't consciously think about shifting gears or checking blind spots - schemas in long-term memory handle these tasks automatically, freeing working memory for higher-level decisions like route planning or conversation.

This is why experts can handle complexity that would overwhelm novices. A chess master analyzing a position isn't processing individual pieces - they recognize patterns and configurations stored as chunked schemas. They perceive the board differently than a beginner, converting what looks like thirty separate elements into three or four meaningful patterns.

Education's goal is building these schemas. The teacher who understands cognitive load helps students develop automated skills efficiently, without overwhelming them during the learning process.

While cognitive load theory emerged from Western educational psychology, its principles appear universal - working memory constraints don't vary across cultures. But how societies apply the theory does vary significantly.

East Asian education systems have long emphasized certain practices that align with cognitive load theory: extensive worked examples in mathematics, careful sequencing of material from simple to complex, and emphasis on mastering fundamentals before advancing.

However, critics note these systems sometimes overemphasize rote learning at the expense of creativity and critical thinking - a reminder that cognitive load optimization is a tool, not an entire educational philosophy.

In Scandinavian countries, educators balance cognitive load management with student agency and exploration-based learning, recognizing that engagement and motivation can help students persist through higher cognitive load when tackling meaningful problems.

The global conversation increasingly recognizes that effective teaching requires both evidence-based understanding of cognitive constraints and culturally responsive practice that respects different learning contexts and values.

"Working memory constraints are universal, but how cultures apply that knowledge varies. Effective teaching needs both cognitive science and cultural responsiveness."

- Global perspective on evidence-based education

How can individual teachers apply cognitive load theory tomorrow?

Start by auditing your materials for extraneous load. Are your slides cluttered? Do students need to flip between multiple sources? Are instructions clear and concise? Eliminating unnecessary cognitive burden is the fastest way to improve learning outcomes.

Use the "I do, we do, you do" framework. Model complete solutions, then work through examples collaboratively, then release students to independent practice. This manages cognitive load as expertise develops.

Check for understanding frequently. Brief checks prevent students from getting lost and building misconceptions that will create massive cognitive load later.

Teach prerequisites explicitly. Don't assume students remember prior material. Brief review activates relevant schemas, connecting new information to existing knowledge.

Embrace silence and wait time. After presenting new information, pause. Let students process before moving forward. The silence feels awkward but learning requires time for information to settle in working memory.

Use dual coding strategically. Combine visual and verbal information, but avoid presenting the same content in both formats simultaneously unless students are very young or have specific learning needs.

Build cognitive load awareness in students. Help them recognize when they're overwhelmed and teach strategies like breaking problems into steps, taking notes to externalize information, and seeking clarification early.

By 2035, understanding cognitive architecture may be as fundamental to teaching credentials as content knowledge is today. We're already seeing cognitive load principles embedded in teacher training programs worldwide.

Artificial intelligence tutoring systems are beginning to monitor cognitive load in real-time, using measures like pupil dilation, response times, and error patterns to adjust difficulty dynamically. Future classrooms may feature ambient technologies that alert teachers when collective cognitive load rises too high.

Virtual and augmented reality offer new possibilities for managing attention and reducing split-attention effects by placing all necessary information in a unified visual field. Educational neuroscience is revealing the brain activity signatures of cognitive overload, potentially enabling precise measurement of what currently requires inference.

But technology alone won't solve the fundamental challenge: human working memory remains stubbornly limited. That's not a problem to overcome - it's a constraint to respect and design around.

The teachers who thrive won't be those with the most content knowledge or the fanciest technology. They'll be the ones who understand that every lesson is a cognitive engineering challenge: how do you transform complex information into a form that can pass through the narrow bottleneck of working memory and emerge as organized schemas in long-term storage?

The answer determines not just whether students pass tests, but whether they develop the deep, flexible understanding that enables them to think, create, and solve problems they've never encountered before. That's the promise of teaching that works with the brain's architecture rather than against it.

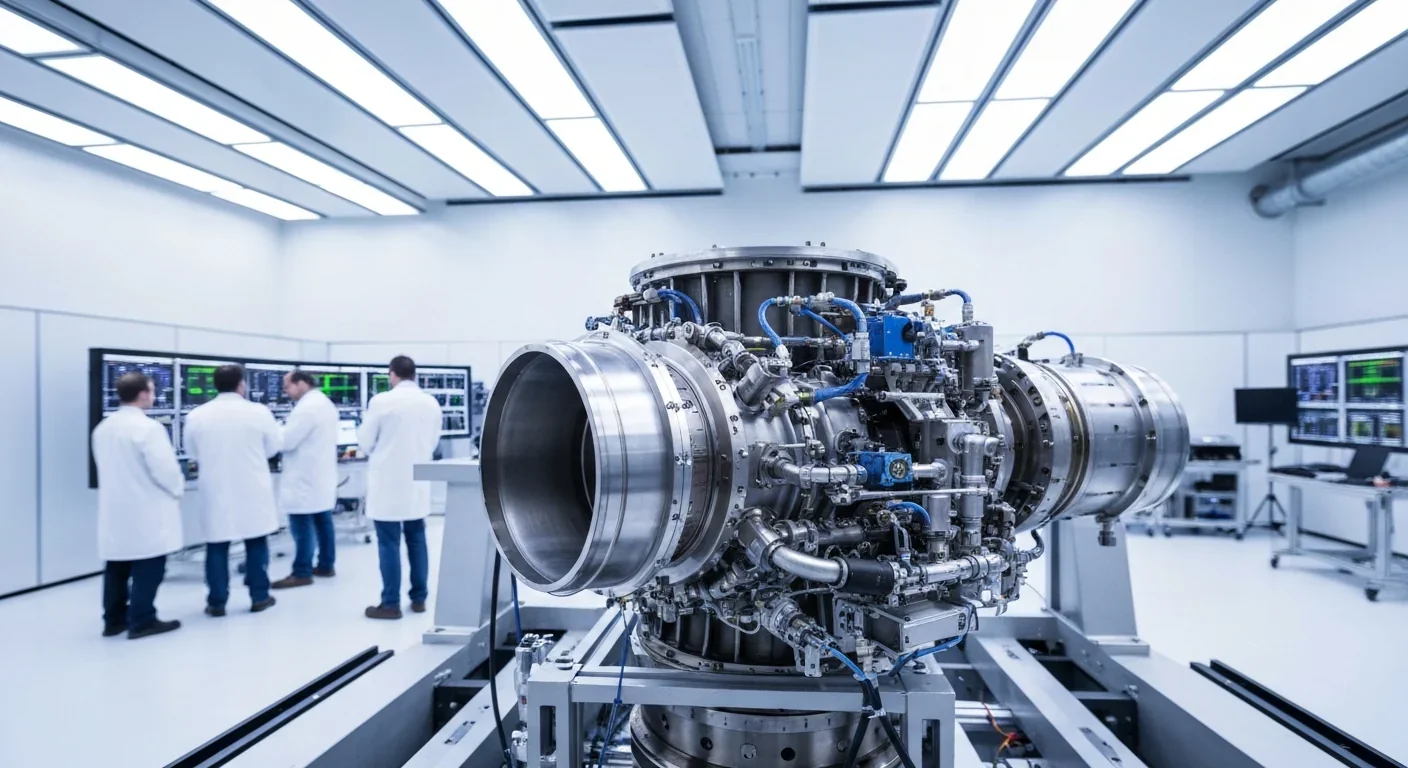

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

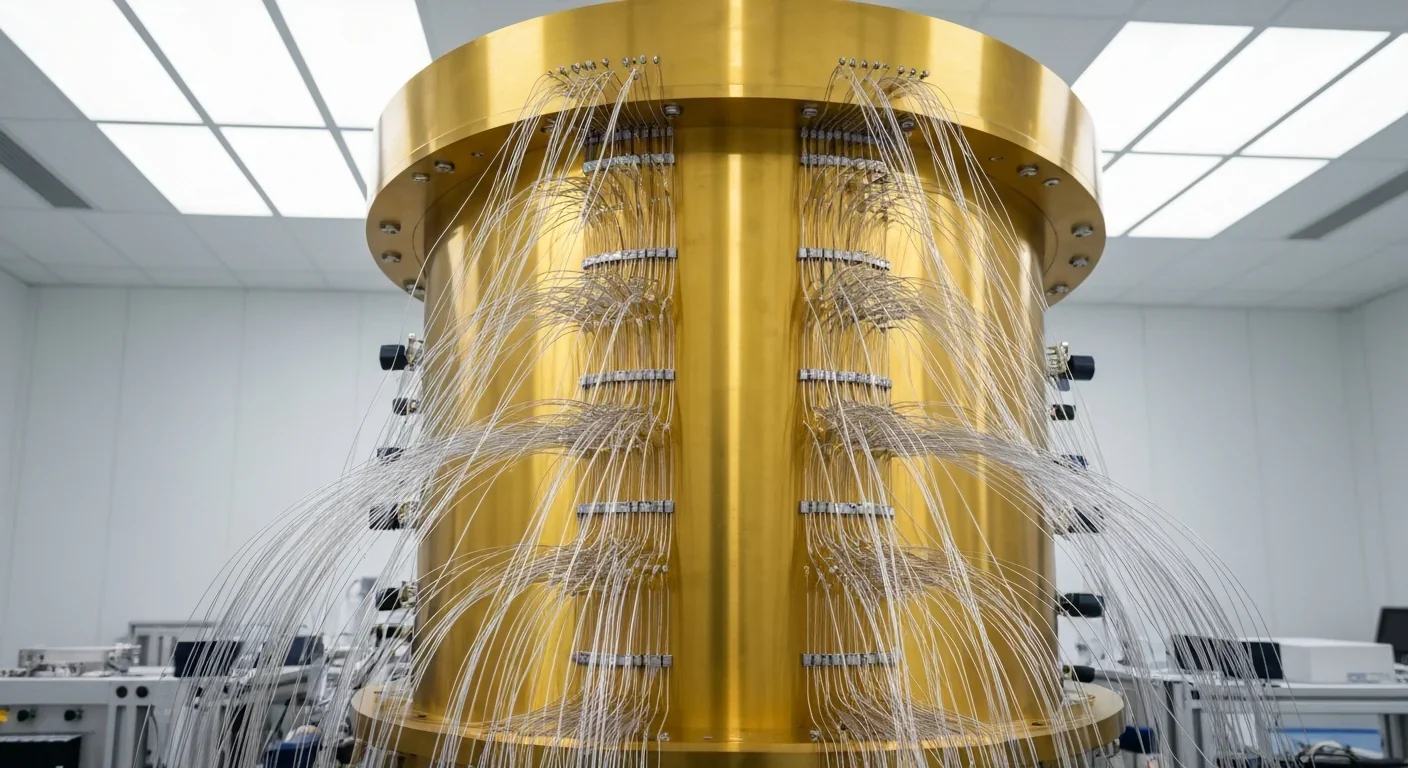

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.