The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The anchoring effect is a cognitive bias where the first number mentioned in a negotiation becomes a reference point, influencing all subsequent judgments. This article explores the psychological mechanisms and provides practical strategies for leveraging and defending against anchoring.

Picture this: you're negotiating your salary for a dream job. The hiring manager opens with $75,000. You were hoping for $90,000, but suddenly that figure feels unreasonable. You counter with $82,000 and settle at $79,000, walking away satisfied. Here's the kicker - if they'd opened at $85,000, you might have walked away with $92,000 instead.

Welcome to the anchoring effect, a cognitive bias so powerful it can shift negotiation outcomes by thousands or even millions of dollars, all because of one number mentioned first.

Anchoring happens when the first number you hear - regardless of its relevance or accuracy - becomes a gravitational force pulling all subsequent judgments toward it. It's not just about numbers in negotiations. This bias affects estimates, decisions, and valuations across every domain of human judgment.

The phenomenon was first documented by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in a deceptively simple experiment. They spun a rigged roulette wheel in front of participants, landing on either 10 or 65. Then they asked: what percentage of African nations are members of the United Nations?

The participants who saw 10 guessed an average of 25%. Those who saw 65 guessed 45%. The random spin of a wheel - completely unrelated to geography or international organizations - shifted estimates by 20 percentage points.

That's anchoring in its purest form: arbitrary information creating real consequences.

The first number in any negotiation creates a psychological gravity well that pulls all subsequent numbers toward it - even when that initial number is completely random.

In another landmark study, behavioral economist Dan Ariely asked MBA students to write down the last two digits of their social security numbers, then bid on various products including wine, chocolate, and computer equipment. Students with higher digits (80-99) bid 60% to 120% higher than those with lower digits (00-19).

Think about that. A number assigned at birth, with zero connection to the value of a bottle of wine, determined how much money people were willing to spend. The anchor didn't just nudge their bids - it fundamentally reshaped their perception of value.

This isn't limited to academic exercises. Research from IMD business school shows that in most negotiation scenarios, whoever makes the first offer gains a material advantage, precisely because that initial number becomes the anchor around which the entire negotiation revolves.

Why does our brain fall for this trick? Researchers have identified two primary mechanisms.

The first is insufficient adjustment. When you hear an anchor, your mind starts there and tries to adjust toward what seems reasonable. But here's the problem: people consistently stop adjusting too soon, once they reach a value that feels plausible rather than accurate. It's cognitive laziness masquerading as efficiency.

The second mechanism is selective accessibility. Once an anchor enters your mind, it activates knowledge consistent with that number while suppressing contradictory information. If someone anchors a house price at $800,000, your brain suddenly recalls the premium finishes, the desirable neighborhood, and comparable high-value sales. Anchor it at $650,000, and you'll notice the outdated kitchen and small backyard instead.

Your brain isn't evaluating the house objectively. It's building a case to justify the anchor, because confirming existing information requires less mental effort than challenging it.

In real estate, listing prices function as powerful anchors that directly influence final sale prices. A study using the Case-Shiller House Price Index found that historical price highs serve as reference points that buyers and sellers unconsciously use to evaluate current value.

List a house high, and buyers adjust their expectations upward. List it low, and even a bidding war might not compensate for the initial anchor pulling the final price downward. The asking price doesn't just signal value - it creates value in buyers' minds.

In employment negotiations, the anchoring effect is particularly consequential. Making the first offer creates a material advantage that persists even when the other party has strong alternatives or when multiple issues are being negotiated simultaneously.

Here's what makes this especially pernicious: the effect holds across cultures and power levels. Whether you're negotiating in New York or Tokyo, whether you're the CEO or the entry-level candidate, the first number spoken carries disproportionate weight.

"Low-power buyers who felt anxious made inferior first offers, especially when facing neutral-power sellers. In one scenario, weak buyers opened at $1,415 while neutral sellers opened at $1,710."

- Study published in Frontiers in Psychology

In complex business negotiations, anchoring effects can shift outcomes by millions. The first offer influences all subsequent proposals, even across multiple issues. If your opponent dismisses your initial offer on one contract term, the anchor still exerts gravitational pull on the other terms being negotiated.

This persistence explains why seasoned negotiators spend considerable time preparing their opening positions. They know that the first credible number on the table will haunt - or help - every subsequent exchange.

One of the most unsettling findings about anchoring is its universality. You might assume that experts in a field would be immune. You'd be wrong.

Studies show that even professionals with deep domain expertise remain susceptible to anchoring. Real estate agents anchor to listing prices. Experienced negotiators anchor to first offers. Automotive sales professionals anchor to sticker prices - even though they know the markup structure intimately.

Why? Because anchoring operates at a level below conscious reasoning. It's not a knowledge problem. It's an architectural feature of how human cognition processes numerical information.

Even more remarkable: anchoring persists when participants are explicitly warned about the phenomenon beforehand. One study gave participants detailed explanations of anchoring bias, cautioning them to be aware of its influence. They still produced higher estimates than control groups when presented with high anchors.

Knowing about the bias doesn't make you immune. Understanding the mechanism doesn't deactivate it.

Emotion doesn't just color our decisions - it fundamentally reshapes how anchoring works.

Research demonstrates that anxiety interacts with power dynamics in negotiations, changing how people respond to anchors. High-anxiety, low-power negotiators make systematically worse first offers because their emotional state reinforces their perception of weakness.

But here's the twist: when both parties have low power, their first offers converge, effectively neutralizing the first-mover advantage. In these scenarios, anxiety creates a kind of equality - though not the productive kind. Both parties anchor low because neither feels confident enough to claim value.

This highlights a broader truth: anchoring doesn't operate in a vacuum. It interacts with context, emotion, power dynamics, and individual psychology to produce outcomes that can shift dramatically based on seemingly minor factors.

While financial negotiations get the most attention, anchoring extends far beyond dollar signs.

Recent research demonstrates that anchoring affects decisions involving sight, sound, and touch. Visual reference points anchor aesthetic judgments. Auditory cues anchor volume and intensity perceptions. Tactile experiences anchor assessments of texture and quality.

In marketing, anchoring drives pricing strategies from "was $199, now $99" discounts to tiered product offerings where the expensive option makes the mid-tier seem reasonable. The high price doesn't need to sell - it just needs to anchor perceptions of value for everything else.

Even artificial intelligence shows evidence of anchoring bias. Large language models in price negotiation simulations exhibit behavior consistent with anchoring effects, suggesting this cognitive pattern may be inherent to systems that process sequential information - whether biological or artificial.

Even artificial intelligence shows evidence of anchoring bias. Large language models in price negotiation simulations exhibit behavior consistent with anchoring effects, suggesting this cognitive pattern may be inherent to systems that process sequential information - whether biological or artificial.

Understanding anchoring means you can deploy it ethically and effectively in your negotiations.

Go first when you can. Making the first offer creates a material advantage in most scenarios. Do your homework, understand the reasonable range, then open at the ambitious end of that range. Your anchor sets the frame for everything that follows.

Use precise numbers. Research indicates that precise anchors (like $79,750 instead of $80,000) carry more psychological weight because they suggest careful calculation rather than arbitrary estimation. Precision implies justification, even when the underlying anchor is no more rational.

Anchor on multiple dimensions. In multi-issue negotiations, don't just anchor on price. Anchor on timelines, deliverables, payment terms, and service levels. Each anchor pulls the negotiation landscape in your direction.

Support your anchor. While the anchor itself can be arbitrary, providing rationale increases its staying power. Market comparisons, cost analyses, or competitive benchmarks give your anchor credibility that makes it harder to dismiss.

Timing matters. Introduce anchors early in the conversation, before substantive discussion has occurred. Once people have formed independent valuations, anchors lose some of their gravitational pull.

Awareness helps, but it's not sufficient. You need active strategies to counteract incoming anchors.

Reject the anchor explicitly. When someone opens with an anchor far from reasonable, don't negotiate from it. Dismiss it outright and establish a new frame. "That's not a number I can work with. Here's the range I'm considering..."

Bring your own anchor. The best defense is a strong offense. If you can't make the first offer, respond immediately with a counter-anchor rather than negotiating from their starting point. Two competing anchors create ambiguity that weakens both.

Focus on objective criteria. Ground the negotiation in external standards - market rates, comparable transactions, cost-plus calculations, industry benchmarks. When both parties anchor to shared data rather than arbitrary proposals, negotiations become more rational.

Use the "consider-the-opposite" strategy. Research shows this technique reliably reduces anchoring bias, especially in group decisions. Actively generate reasons why the anchor might be wrong, too high, or too low. This cognitive exercise activates contradictory information that the anchor would otherwise suppress.

Take time. Anchoring effects strengthen under time pressure and weaken with deliberation. If possible, postpone immediate reactions to anchors. Sleep on it. Consult with colleagues. Distance yourself from the emotional and cognitive pull of the initial number.

Reframe the negotiation. Instead of arguing about the specific number, shift the conversation to principles, needs, and interests. "Rather than debate this figure, let's talk about what we're each trying to accomplish and work backward from there."

Negotiations don't always happen one-on-one. How does anchoring work in group settings?

Research shows that the first speaker in a group negotiation has disproportionate influence on the final outcome. Their anchor shapes not just their own position but the positions of everyone who speaks afterward. This creates a compounding effect where early anchors become group consensus.

However, there are strategies to mitigate group anchoring. Process accountability - requiring groups to explain their reasoning - and competitive rather than cooperative motivation can reduce anchoring effects by encouraging critical evaluation rather than conformity.

In team negotiations, assign someone the explicit role of challenging anchors. Having a designated skeptic who questions numerical assumptions can prevent the whole team from unconsciously drifting toward an opponent's anchor.

"The first speaker in a group negotiation has disproportionate influence. Their anchor shapes not just their own position but everyone who speaks afterward, creating a compounding effect where early anchors become group consensus."

- Anchoring Effect Research

Does anchoring work the same way across different cultures?

The research suggests anchoring is fundamentally cross-cultural, though the magnitude and specific manifestations may vary. Studies conducted in Western and Israeli populations show comparable effects, suggesting that anchoring taps into universal cognitive architecture rather than culture-specific heuristics.

That said, cultural norms around negotiation style, directness, and relationship-building influence how anchors are deployed and received. In high-context cultures where relationships precede transactions, aggressive anchoring might damage rapport. In low-context, transactional cultures, strong opening anchors are expected and respected.

The bias itself is universal. The socially acceptable way to leverage it varies by context.

Understanding anchoring intellectually and applying counter-strategies effectively are different skills. Here are the most common errors people make:

Anchoring yourself. Sometimes we generate our own anchors by researching salary ranges, looking at comparable prices, or consulting with peers - then treating that information as fixed truth rather than a starting point for analysis. Be aware of your own anchors, not just others'.

Overcompensating. Knowing about anchoring can lead to overcorrection, where you reject reasonable offers simply because you're hypersensitive to being influenced. The goal isn't to eliminate all external reference points - it's to evaluate them critically.

Ignoring the relationship. Aggressive counter-anchoring can damage trust and rapport, especially in negotiations where long-term relationships matter more than immediate outcomes. Choose your battles.

Assuming rationality will prevail. Simply presenting objective data doesn't deactivate an anchor. You need to explicitly reframe the conversation and establish new reference points, not just provide information and assume people will recalibrate.

The science of anchoring continues to evolve in fascinating directions.

Researchers are now exploring whether anchoring affects AI systems, with implications for automated negotiation systems and pricing algorithms. Early evidence suggests that large language models exhibit anchoring-like behavior.

Studies on numerical precision reveal how round versus precise numbers activate different mental reference points. Investigations into expertise show that familiarity doesn't reduce anchoring, but the perceived relevance of the anchor does matter.

Here's what you need to remember when you're sitting across from someone who wants your money, your time, or your agreement:

The first number has power. Don't fear it, but don't ignore it either. Prepare your own anchor beforehand so you're not caught off-guard.

Arbitrary doesn't mean powerless. Even random numbers influence judgment. Don't assume you're immune because an anchor seems baseless.

Strategy beats instinct. Active counter-strategies work better than relying on awareness alone. Have a plan for how you'll respond to anchors.

Context shapes everything. Power dynamics, emotions, relationships, and cultural norms all modulate how anchoring works. Read the room and adapt accordingly.

Practice matters. Like any negotiation skill, defending against and deploying anchors improves with deliberate practice. Reflect on your negotiations. Identify where anchors shaped outcomes. Refine your approach.

The next time someone opens a negotiation with a number, pause and ask yourself: is this number anchoring me? What would I think was fair if I'd never heard it? What objective criteria should actually drive this decision?

The anchoring effect is more than a negotiation tactic. It's a window into how human minds construct reality from fragments of information, often in ways that feel rational but are profoundly influenced by arbitrary starting points.

Understanding anchoring means understanding that our perception of value, fairness, and reasonableness isn't purely objective. It's shaped by context, sequence, and the accidents of what information arrives first.

This realization is simultaneously unsettling and empowering. Unsettling because it reveals how much of our decision-making happens below conscious awareness. Empowering because once you see the pattern, you can work with it rather than against it.

The next time someone opens a negotiation with a number, pause. Ask yourself: is this number anchoring me? What would I think was fair if I'd never heard it? What objective criteria should actually drive this decision?

Those questions won't make you immune to anchoring. But they'll give you a fighting chance to negotiate on your terms, not theirs.

And in a world where the first number spoken can shift outcomes by thousands or millions, that fighting chance is worth everything.

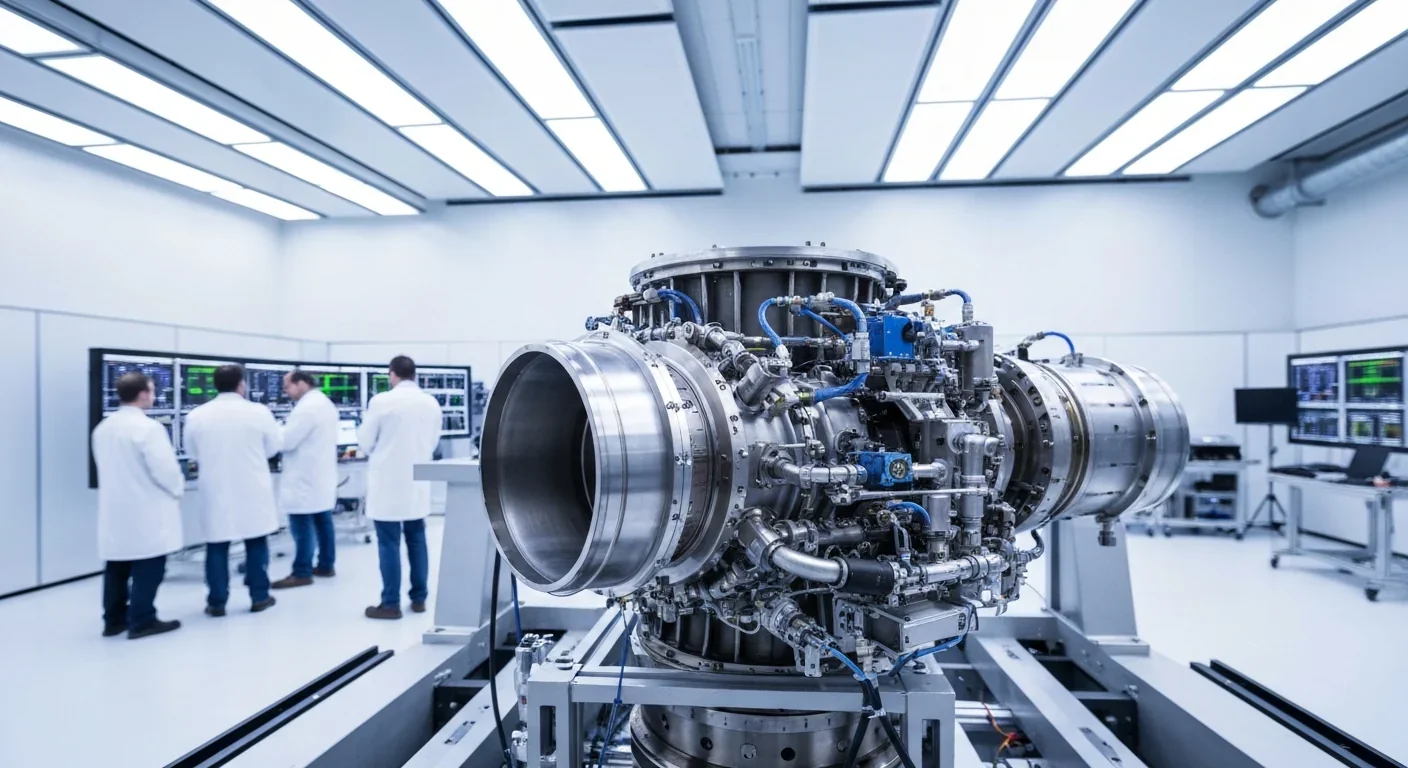

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

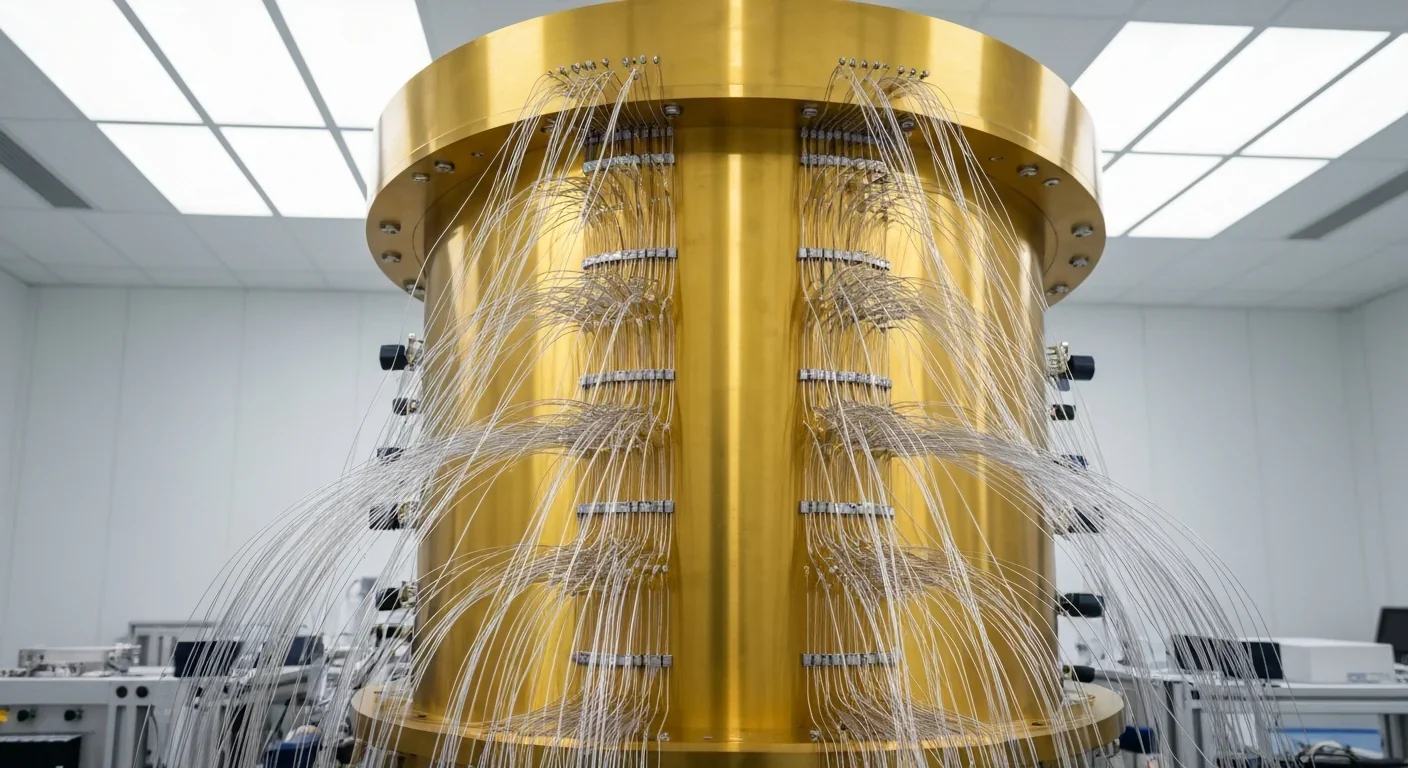

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.