Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: New neuroscience reveals infants can encode memories from age one, but childhood amnesia prevents adult recall - not because memories weren't formed, but because retrieval systems fail to unlock them.

Your earliest memories are probably false. Not distorted, not embellished - completely fabricated. The birthday party you "remember" from age two, that family vacation when you were three - neuroscience suggests these recollections are reconstructions built from photographs, family stories, and your imagination rather than authentic neural recordings of lived experience.

This isn't a failure of memory. It's how human consciousness is designed to work.

Scientists call this phenomenon childhood amnesia, and it affects virtually every person on Earth. Most adults cannot recall any events from before age three or four, and memories from ages three to seven remain sparse and unreliable. What makes this universal experience so fascinating isn't just that we forget our earliest years - it's that new research reveals we actually do form memories during infancy, but something prevents us from ever retrieving them later in life.

The mystery isn't about memory formation. It's about a retrieval system that won't unlock what's already stored.

For decades, scientists assumed that the infant brain simply couldn't encode lasting memories. The working theory went like this: the hippocampus - the brain's memory-recording hub - remained too immature during the first years of life to create the complex neural patterns required for autobiographical recall.

That assumption just collapsed.

Research published in Neuroscience News using functional MRI scans of awake infants revealed something remarkable: babies as young as 12 months show clear hippocampal activation during memory tasks. When researchers tracked the brain activity of infants viewing faces, scenes, and objects, the hippocampus lit up in patterns that mirror adult memory encoding. The neural machinery for creating memories isn't absent in infancy. It's already running.

Dr. Tristan Yates and his colleagues at Princeton studied this phenomenon in 598 participants aged 4 to 25 months, using a preferential-looking memory paradigm. The results were unambiguous: infant brains possess the fundamental capacity to encode individual experiences into episodic memory traces - what neuroscientists call "engrams" - starting around the first birthday.

But here's where it gets strange. If infants can encode memories, why can't adults access them?

The mystery of childhood amnesia isn't that young brains can't record experiences - it's that adult brains can't retrieve what was recorded years earlier.

Studies in rodents offered the first compelling clue. When researchers artificially stimulated specific hippocampal neurons in adult rats - neurons that had encoded experiences during infancy - those early memories suddenly became accessible. The engrams weren't erased. They were locked away, inaccessible through normal recall mechanisms but still physically present in the neural architecture.

"Infant memories may persist but remain inaccessible for retrieval without direct stimulation of hippocampal engrams or reminder cues," Yates explained. The implication is profound: your earliest experiences might still exist as neural patterns somewhere in your brain, but evolution or development has hidden the keys.

Understanding why infant memories stay locked requires examining how the hippocampus develops. This seahorse-shaped structure tucked deep in the brain's temporal lobes doesn't simply turn on one day like a light switch. It undergoes a long, complex maturation process that extends well into early childhood.

According to a comprehensive review in the Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, the hippocampus remains functionally immature during the first two years of life, making the encoding of explicit, episodic memories difficult despite the presence of basic encoding machinery. Think of it as having a camera with a functional sensor but no lens, storage card, or processing chip yet installed.

One of the key culprits is neurogenesis - the birth of new neurons. In most of the adult brain, neurogenesis stops after early development. But the hippocampus remains one of the few brain regions where new neurons continue to form throughout life, with particularly high rates during infancy and early childhood.

Paradoxically, this abundance of new neurons may actually impair memory retention rather than enhance it. As fresh neurons integrate into existing hippocampal circuits, they disrupt the precise spatiotemporal activation patterns required to maintain memory fidelity. It's like constantly renovating a library while trying to maintain an accurate catalog - eventually, you lose track of where everything was shelved.

Research shows that animals with artificially reduced neurogenesis actually perform worse at certain hippocampal-dependent learning tasks, while those with higher neurogenesis rates show increased forgetting. This suggests neurogenesis serves a dual purpose: it supports new learning capacity while simultaneously clearing out old, potentially outdated information - including your earliest experiences.

"In children, it's more of a gradual transition of function along the hippocampus's long axis, like a color gradient rather than two distinct blocks."

- Dr. Hua (Oliver) Xie, Children's National Hospital

Recent work from Children's National Hospital examined how the hippocampus specializes along its longitudinal axis as children mature into adolescence. Using resting-state fMRI data from 598 participants aged 8 to 21, researchers discovered that the head and tail of the hippocampus gradually develop distinct communication patterns with other brain regions - a specialization that predicts how well children can form episodic memories.

The hippocampus doesn't fully mature until approximately age five to seven. Until then, its circuitry remains in flux, constantly rewiring itself as new neurons arrive and old connections get pruned. This ongoing construction project makes it nearly impossible to maintain stable memory traces from infancy into adulthood.

But the hippocampus isn't working alone. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a brain region crucial for organizing autobiographical memories into coherent narratives, matures even later than the hippocampus. Without this region's ability to weave individual experiences into a continuous life story, early memories lack the contextual scaffolding needed for long-term retrieval.

Not all memory systems develop on the same schedule. The human brain employs multiple types of memory, each governed by different neural circuits that mature at different rates during childhood.

Procedural memory - the system that handles skills and habits - comes online first. Babies can remember how to crawl, grasp objects, and recognize faces within the first months of life. These motor and perceptual memories rely on brain structures like the basal ganglia and cerebellum, which mature relatively early.

Semantic memory - our knowledge of facts, concepts, and word meanings - begins developing as language emerges around age one to two. Though infants can't yet form autobiographical memories, they're busy cataloging information about the world: what objects are called, how people behave, which foods taste good.

Episodic memory - the capacity to mentally travel back in time and re-experience specific events from your personal past - is the last system to develop. This is the type of memory affected by childhood amnesia, and it requires the coordinated maturation of multiple brain regions including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and parietal lobes.

The timeline for episodic memory development correlates remarkably well with language acquisition. Children begin using past tense language around age two to three, which coincides with the earliest memories that adults can reliably recall. This isn't coincidental - language provides the cognitive framework necessary for encoding experiences as narratives that can be stored and retrieved later.

The average age of first memory sits right at the boundary where multiple developmental milestones converge: language mastery, self-concept emergence, and hippocampal maturation.

Research suggests that the transition from latent to explicit memory systems occurs during a critical period mediated by language and self-concept maturation. Before age three, children lack the linguistic tools to encode experiences in a format compatible with later adult recall. They experience events, they react emotionally, they learn patterns - but they don't yet create the verbal narratives that allow memories to be filed away for long-term retrieval.

Think of it this way: if your brain is a library, early childhood experiences are like books written in a language you hadn't yet learned to read. The books exist, but without the right decoding system, their contents remain inaccessible.

Beyond brain structure, the chemistry of memory itself plays a role in childhood amnesia. One neurotransmitter system in particular - GABAergic signaling - appears crucial for regulating what gets remembered and what gets erased during early development.

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is the brain's primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, responsible for putting the brakes on neural activity. In the context of memory, GABAergic neurotransmission plays a key role in memory extinction - the process by which previously learned associations gradually fade.

Studies show that blocking GABA-A receptors in the amygdala enhances fear memory retention, while activating them impairs it. This indicates that inhibitory learning underlies extinction processes that may be related to infantile amnesia. In other words, the brain uses GABA signaling to actively erase or suppress memories it deems unnecessary or outdated.

During early childhood, when GABAergic systems are still developing, this balance between memory formation and memory extinction may be tilted toward forgetting. High rates of hippocampal neurogenesis combined with immature inhibitory circuits could create an environment where memories form easily but also dissolve quickly - perfect for a brain that needs maximum plasticity to adapt to a rapidly changing understanding of the world.

This raises a fascinating question: Could we pharmacologically manipulate GABAergic systems to reduce childhood amnesia or even retrieve lost infant memories? Research in rodents suggests this might be theoretically possible, though the ethical implications of tampering with memory suppression mechanisms remain deeply uncertain.

Though explicit autobiographical memories from before age three remain inaccessible to most adults, that doesn't mean early experiences leave no trace. Research consistently shows that children under two can remember events for weeks or months, even if these memories eventually fade from conscious recall.

More importantly, early experiences continue to influence us through implicit memory systems - unconscious patterns that shape behavior, emotional responses, and preferences without any conscious awareness of their origins. The fear of dogs you developed after being bitten as an 18-month-old may persist even if you have no explicit memory of the incident. Your comfort with physical affection, your baseline anxiety level, your attachment style in relationships - all potentially influenced by pre-verbal experiences you'll never consciously remember.

Some memories from early childhood do persist, but they're often the exceptions that prove the rule. Highly emotional or traumatic events sometimes create fragments of recall from age two or three, though psychologists caution these memories are particularly susceptible to distortion and reconstruction over time.

A particularly intriguing finding: when adults report detailed memories from before age three, these recollections often turn out to be "false memories" - not intentional lies, but reconstructions based on photographs, home videos, or stories told by family members. Your brain fills in sensory details, spatial layouts, and emotional tones to create what feels like an authentic first-person memory, even though the original experience left no recoverable neural trace.

The phenomenon isn't evidence of dishonesty or fantasy. It's just how memory works. The brain is a storyteller, not a video recorder, and it will happily create plausible narratives to fill gaps in the historical record.

The boundary between remembering and forgetting isn't fixed by biology alone - it's negotiated between developing neural circuits and the cultural practices that shape how we encode experience.

While childhood amnesia appears universal across human populations, the precise age at which lasting memories begin shows intriguing cultural variation. Some research suggests that the average age of first memory occurs earlier in East Asian populations compared to Western European and North American groups, though the mechanisms behind this difference remain debated.

One hypothesis centers on cultural differences in how parents talk to children about past experiences. In cultures where parents engage in more elaborate, emotion-focused reminiscing with their young children, those children may develop earlier and more detailed autobiographical memories. The practice of frequently discussing past events may help children build the narrative scaffolding needed to encode experiences in a format compatible with long-term retrieval.

Language structure itself might play a role. Some linguistic features - like how languages mark tense, encode perspective, or structure narratives - could influence the cognitive tools available for organizing autobiographical memory. Though this remains speculative, it highlights an important principle: childhood amnesia isn't purely biological. It emerges from the interaction between brain development and the cultural-linguistic environment in which that development occurs.

Individual differences matter too. Some people report clear memories from age two or three that appear genuine rather than reconstructed, while others struggle to recall anything before age five or six. The factors behind this variation - genetic differences in hippocampal development, early language exposure, quality of attachment relationships, or simple measurement error - remain active areas of investigation.

The emerging picture of childhood amnesia challenges some fundamental assumptions about memory and identity. If you have no conscious access to the first three years of your life - a period that encompasses learning to walk, talk, recognize faces, and navigate social relationships - in what sense are those experiences part of "your" story?

Philosophers and psychologists have long debated whether continuous memory is necessary for personal identity to persist over time. Childhood amnesia provides a natural experiment: you are undeniably the same person who existed as a two-year-old, yet you share no autobiographical memories with that version of yourself. The physical continuity is clear, but the psychological continuity - the felt sense of being the same conscious entity - is broken.

Perhaps this discontinuity serves a purpose. Some researchers have proposed that childhood amnesia may serve an evolutionary function in allowing the developing brain maximum plasticity to adapt to its environment. By clearing the slate of early, potentially unreliable memory traces, the brain makes room for the more sophisticated learning that emerges once language and self-concept mature.

Think of it as a form of cognitive metamorphosis. Just as a caterpillar's neural tissue reorganizes during pupation to support the dramatically different needs of a butterfly, the human brain may need to reorganize its memory systems to support the transition from pre-linguistic infant to language-using child. Early memories become casualties of this transformation - dissolved to make way for a more capable consciousness.

The science of childhood amnesia carries practical implications for how we think about parenting and early childhood experiences. If children won't remember their first years, should parents worry less about those experiences?

Neuroscientists and developmental psychologists offer a resounding no.

Though explicit autobiographical memories fade, the implicit effects of early experiences persist throughout life. The quality of attachment relationships formed in infancy, the degree of stress or security a young child experiences, the language exposure and social interaction they receive - all these factors shape brain architecture in ways that remain long after conscious memory fades.

Research on early childhood stress and adversity shows that negative experiences during the first years can alter stress response systems, affect emotional regulation, and increase vulnerability to mental health challenges later in life - even when the individual has no conscious memory of the original trauma. The body remembers what the mind forgets.

Conversely, secure attachment, rich language exposure, and responsive caregiving during the pre-memory years create neural foundations that support cognitive and emotional development throughout childhood and beyond. Parents aren't creating memories during these years - they're building brains.

"Infant memories may persist but remain inaccessible for retrieval without direct stimulation of hippocampal engrams or reminder cues."

- Tristan Yates, Princeton University

Some parents worry about whether children remember traumatic medical procedures or brief separations that occur before age three. While the explicit memory will likely fade, research suggests that reminder cues can sometimes reactivate otherwise inaccessible infant memories. Contextual cues associated with early experiences - a particular smell, location, or emotional state - might trigger fragments of implicit recall even without conscious awareness.

This suggests a middle path: early experiences matter profoundly, but not necessarily in the way we typically think of memory mattering. The goal isn't to create experiences children will remember, but rather to create experiences that build healthy neural architecture for the person they're becoming.

Modern neuroscience techniques are revealing new insights about infant memory capacity at an accelerating pace. Advances in fMRI technology now allow researchers to study brain activity in awake, behaving infants in ways that were impossible just a decade ago. As these tools become more sophisticated, we're gaining unprecedented access to the neural processes underlying memory formation in the earliest stages of life.

One particularly exciting avenue involves the possibility of retrieving inaccessible infant memories through targeted reminder cues or even direct neural stimulation. If rodent studies hold true for humans - that infant memories persist as dormant engrams rather than being permanently erased - it raises the possibility of developing techniques to reactivate those traces.

Would we want to? The question carries both scientific and ethical dimensions. Accessing lost memories could provide valuable insights into early development and potentially help resolve questions about early trauma. But it could also introduce false memories, create psychological distress, or violate the natural boundaries that evolution placed on human memory for potentially good reasons.

Research into the hippocampal gradient - the finding that the hippocampus specializes along its length in a continuous gradient rather than discrete modules - may help explain individual differences in memory onset. If we can identify neural markers that predict when a child's memory systems will mature, we might be able to better understand variations in cognitive development and potentially identify children who would benefit from early intervention.

The role of GABAergic neurotransmission in memory extinction also presents therapeutic possibilities. Understanding how inhibitory learning shapes what gets remembered and what gets forgotten could inform treatments for PTSD, anxiety disorders, and other conditions where the inability to forget causes suffering.

In the end, childhood amnesia reminds us that human consciousness is far stranger than our everyday experience suggests. We walk through life convinced that memory defines identity, that we are the sum of what we remember. Yet every human being exists as a fundamentally split entity: the person we consciously recall being, and the earlier self who exists only through photographs, family stories, and implicit traces buried in neural circuits we cannot access.

The first three years of life remain hidden behind a locked vault. The experiences are there - or at least their effects persist - but the retrieval system refuses to grant access. Whether this represents a developmental necessity, an evolutionary adaptation, or simply an unavoidable consequence of how brains grow remains an open question.

What's clear is that forgetting, like remembering, is not a bug in the system. It's a feature.

The infant who existed before memory began was no less real for being unremembered. That child learned to recognize faces, developed preferences, felt joy and fear, built the foundational architecture of the mind that's reading these words right now. All of it happened. None of it can be recalled.

And maybe that's exactly how it should be. Perhaps consciousness needs to shed its earliest iterations the way a snake sheds its skin - not erasing the past, but making space for the growth that transforms us into whoever we're becoming next.

Your earliest memories are likely false, but your earliest experiences were undeniably real. They made you who you are, even if you'll never remember how.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

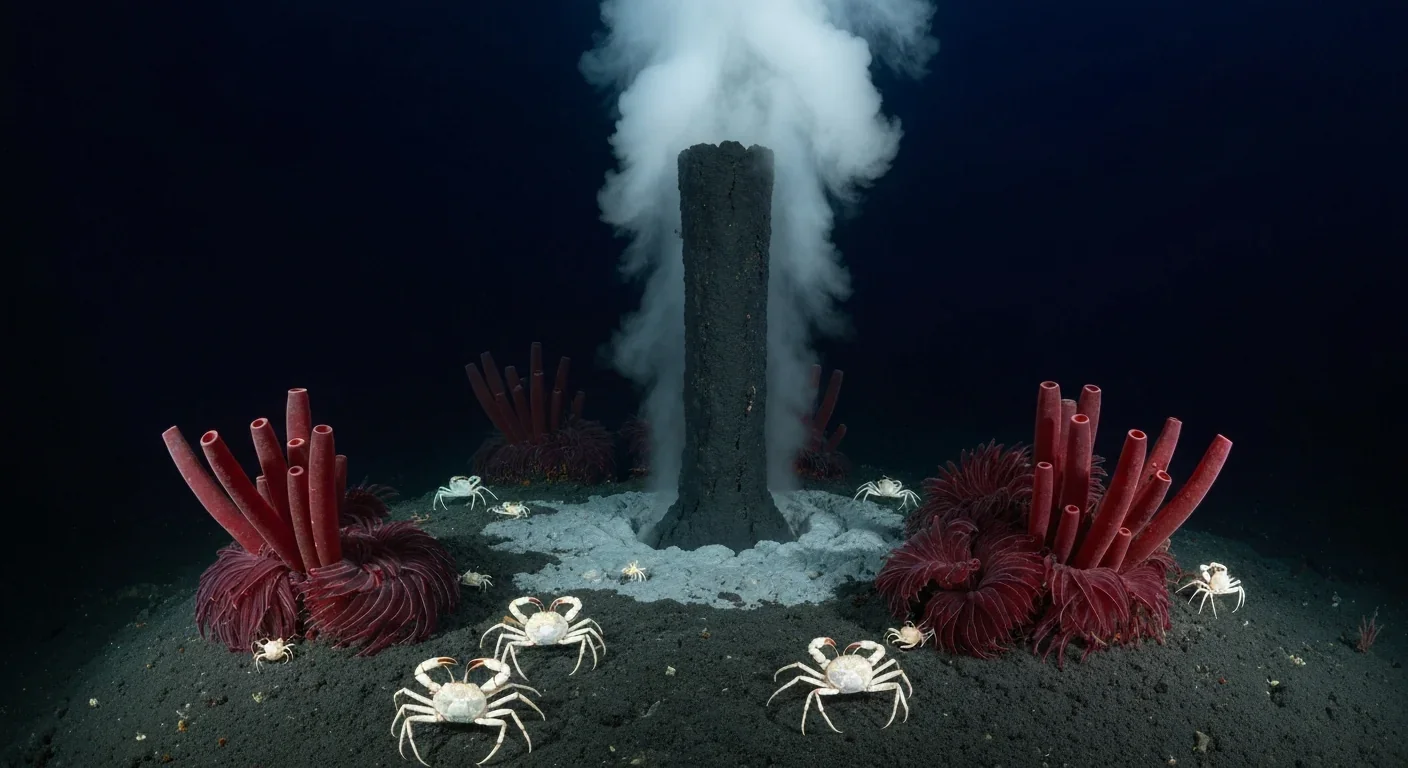

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.