Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: The online disinhibition effect explains why people behave differently behind screens. Research reveals it's driven by six factors including anonymity and invisibility, creating both toxic behaviors like cyberbullying and benign outcomes like mental health support. Understanding the neuroscience behind this phenomenon and how platform design shapes it can help us navigate digital spaces more thoughtfully.

You've seen it. Maybe you've done it. Someone who's polite at dinner parties transforms into a keyboard warrior the moment they log on. The shy colleague becomes a relentless troll. Your aunt who bakes cookies for neighbors shares conspiracy theories with a viciousness that would make a Roman gladiator blush. Welcome to the online disinhibition effect, where the internet doesn't just connect us - it rewires how we behave.

Back in 2004, psychologist John Suler identified six factors that together create what he called the online disinhibition effect. Think of them as psychological accelerants that, when combined, can either spark a bonfire of toxicity or light a candle of genuine connection.

First comes dissociative anonymity - the feeling that your online self exists separately from your real-world identity. You can be @DarkKnight2024 and never have that username traced back to the person who picks up dry cleaning on Thursdays. This psychological distance creates a buffer between action and consequence.

Then there's invisibility. You can't see the facial expressions of people reading your comments. They can't see you typing them. Without those visual cues, your brain processes the interaction differently than it would face-to-face. Neuroscience research shows that digital interactions fundamentally alter how the brain handles social exchanges because they lack the nonverbal signals - facial expressions, tone, body language - that normally activate our empathy circuits.

Asynchronicity plays a role too. You don't have to deal with immediate reactions. You can drop a comment bomb and walk away, never witnessing the emotional shrapnel. The brain's anterior insula cortex and midcingulate cortex - regions that light up when we experience pain or empathize with someone else's pain - don't fire the same way when we're not there to see the impact.

Solipsistic introjection makes online conversations feel like they're happening inside your head. You read text in your own voice, imagine tone and intent through your own lens, and sometimes forget there's an actual human on the other end. It becomes a dialogue with yourself.

Dissociative imagination lets you treat online spaces like fantasy realms where normal rules don't apply. "It's just the internet" becomes a permission slip for behavior you'd never exhibit in person.

And finally, minimization of authority - online, there's often no boss, no parent, no authority figure watching. The usual social hierarchies flatten, and with them, the restraints they impose.

Here's where it gets interesting: online disinhibition isn't inherently evil. Suler distinguished between two flavors - toxic and benign - and understanding the difference matters more than ever.

Toxic disinhibition manifests as cyberbullying, trolling, hate speech, harassment, and those comment sections that make you lose faith in humanity. A 2023 NIH study found a statistically significant correlation between user anonymity and increased hostile online behavior. A 2019 FBI report emphasized how anonymous platforms get exploited to radicalize individuals and coordinate extremist activities.

Recent research from Frontiers in Public Health examined 1,574 Chinese adolescents and found that toxic online disinhibition significantly moderated the relationship between trait anger and cyberbullying perpetration. Among participants with high toxic disinhibition, the link between anger and cyberbullying was strong and significant; among those with low toxic disinhibition, that relationship vanished. In other words, the online environment doesn't create aggression - it amplifies what's already there.

But benign disinhibition? That's the flip side. It's people opening up about mental health struggles on Reddit forums where anonymity creates safety. It's LGBTQ+ teens finding communities where they can explore identity without fear. It's whistleblowers exposing corruption, activists organizing in oppressive regimes, and people seeking help for stigmatized issues they'd never discuss face-to-face.

"Online anonymity is neither inherently good nor bad - it's a tool, and like all tools, its impact depends on how it's used."

- Research on Internet Psychology

Research on cyber dating abuse discovered something fascinating: benign online disinhibition actually negatively predicted direct aggression. People who felt comfortable being emotionally open online were less likely to engage in hostile behavior. The same conditions that can unleash cruelty can also foster extraordinary kindness and vulnerability.

So why does a screen change everything? The neuroscience is revealing. When you communicate face-to-face, your brain is doing incredible work. Mirror neurons fire, helping you simulate what the other person is feeling. Your amygdala processes emotional cues. Your prefrontal cortex integrates social context and regulates your responses.

Online, much of that machinery goes idle. Brain imaging studies using functional MRI scanned 66 adults while they listened to real stories of human distress. Researchers found that empathic care activates reward-processing circuits like the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and medial orbitofrontal cortex - the same regions involved in experiencing pleasure and assessing value. Empathic distress, by contrast, engaged mirroring systems including premotor and somatosensory cortices, essentially making your brain simulate the other person's experience.

But here's the catch: these systems evolved for in-person interaction. Text on a screen doesn't trigger the same cascade. You're essentially flying blind, navigating social situations without half your instruments. It's not that you're a worse person online - your brain just has less information to work with, and the feedback loops that normally keep behavior in check are broken.

The emotional distance created by screens means you don't feel the weight of your words the same way. In conversation, if you say something hurtful, you see the person flinch, hear their voice change, notice them withdraw. Those signals course-correct your behavior in real time. Online, you get none of that. You might get an angry reply hours later, but by then you've already moved on.

For years, the conventional wisdom was simple: anonymity breeds toxicity, so make people use real names. Facebook tried it. South Korea even passed a law in 2007 requiring real-name verification for online comments. That law was struck down in 2012 after evidence suggested it wasn't working as intended.

The truth is more nuanced. A fascinating study analyzed 45 million comments from Huffington Post across three phases: easy anonymity, durable pseudonyms, and real names via Facebook integration. Researchers found that stable pseudonyms - where users create a consistent identity within a forum - produced the best results. Swear words dropped significantly, and the cognitive complexity of comments increased.

Then came the real-name phase. Comment quality actually declined compared to the pseudonym era. Why? Because what matters isn't whether people know your legal name - it's whether you're invested in your persona and accountable for its behavior within a specific community.

What matters isn't whether people know your legal name - it's whether you're invested in your persona and accountable for its behavior within a specific community.

Think about Reddit's system. Accounts aren't anonymous in the "burn this identity and create a new one" sense. They're pseudonymous. Users build reputation, karma, community standing. That investment creates accountability. Meanwhile, Facebook comments using real names can still be toxic because there's no reputation cost within the platform's sprawling, impersonal ecosystem.

The Chinese adolescent study provides another data point: even within a real-name registration system, toxic online disinhibition remained a strong predictor of cyberbullying. Anonymity is one lever, but it's not the only one. The research suggests that disinhibition operates through other mechanisms too - asynchronicity, the perceived distance of digital communication, the lack of immediate consequence.

Platform design isn't neutral. Every choice - from how avatars work to whether you can edit comments to how moderation functions - shapes the disinhibition effect.

Consider Twitter (now X) versus LinkedIn. On Twitter, the design encourages quick, reactive posting. Character limits reward snark. The algorithm surfaces conflict because engagement metrics favor controversy. On LinkedIn, longer-form content dominates, professional reputation is at stake, and the norms are explicitly civil. Same humans, radically different behavior.

Research suggests that community moderation empowering users to flag content can preserve anonymity's benefits while reducing toxicity. Behavioral tracking that doesn't store personal data can identify repeat offenders without compromising privacy. These aren't theoretical - platforms like Wikipedia have demonstrated that well-designed community governance can maintain civil discourse even with pseudonymous contributors.

Reputation systems work. Stack Overflow uses them brilliantly - points, badges, and voting create accountability without requiring real names. Twitch does something similar with subscriber badges and channel-specific emotes that signal community membership. When your standing in a community you value is at stake, disinhibition decreases.

Moderation approaches matter too. Heavy-handed algorithmic moderation often backfires, creating cat-and-mouse games where users find creative ways around filters. Community-driven moderation, where trusted members can sanction others, tends to work better because it leverages social dynamics rather than fighting them.

The consequences of toxic disinhibition are serious and growing. Cyberbullying has been linked to depression, anxiety, and suicide among young people. The empathic distress research found that even experiencing negative emotions online activates brain regions associated with sadness, anger, fear, and disgust - and chronic exposure can lead to burnout and withdrawal.

But perhaps the most concerning dimension is online radicalization. Anonymous forums provide spaces where extreme views can be validated and amplified without social cost. The feedback loops are insidious: someone expresses a fringe opinion, finds others who agree, receives social validation, and becomes more extreme. Algorithms designed to maximize engagement actively accelerate this process by surfacing increasingly radical content.

The FBI's 2019 report on extremism highlighted how platforms like 8chan and similar spaces have been used to coordinate real-world violence. The disinhibition effect doesn't just change what people say - it changes what they believe is acceptable to do.

"The brain is not a modular system where there's a region that manages empathy. When listening, the brain is a distributed system, not just one region."

- Dr. Tor Wager, Neuroscientist

Political polarization follows similar dynamics. When you only see opponents as usernames and profile pictures, it's easier to dehumanize them. The empathy circuits that might soften your stance or help you understand different perspectives simply don't engage. Add in echo chambers reinforced by algorithmic curation, and you get tribal warfare masquerading as political discourse.

Online disinhibition doesn't affect everyone equally. Cultural norms shape how people experience and express it. Collectivist cultures, where group harmony is valued over individual expression, may experience less toxic disinhibition - or express it differently - than individualistic cultures.

Age matters too. Digital natives who grew up online have different baseline expectations about digital behavior. They're more fluent in emoji, memes, and other tools that add emotional context to text. They're also more likely to understand that online personas are curated performances rather than authentic selves.

Gender plays a significant role. Research on cyber dating abuse found that women experience online harassment differently than men, with different psychological impacts and coping mechanisms. The empathy gaps created by disinhibition can amplify existing societal inequalities.

There's also the question of neurodiversity. People on the autism spectrum, for instance, may find text-based communication easier than face-to-face interaction because it removes some of the challenging aspects of reading social cues. For them, online disinhibition might actually reduce anxiety and improve communication quality - a reminder that "disinhibition" isn't always negative.

Just when we thought we understood online disinhibition, technology shifted again. AI and deepfakes introduce new dimensions to the phenomenon.

Research on AI chatbots reveals an "empathy gap" - these systems are typically trained on adult datasets and may lack appropriate context when interacting with children or vulnerable populations. They can produce responses that are age-inappropriate or distressing, creating interactions that feel human enough to engage emotional responses but lack genuine empathy.

Deepfakes take it further. When you can create convincing video of someone saying things they never said, the distinction between online persona and reality blurs dangerously. The disinhibition effect could amplify: if people believe fake videos are real, the emotional impact is genuine. And if creators of deepfakes can remain anonymous, they face no consequence for manufacturing reality.

We're entering an era where verifying what's real online becomes increasingly difficult. The psychological mechanisms that Suler identified in 2004 - dissociative anonymity, invisibility, asynchronicity - may operate in new ways when AI can generate realistic but fake human interactions at scale.

So what do we do about all this? Both individual strategies and platform-level interventions show promise.

For individuals, the key is awareness. Recognizing when you're experiencing disinhibition is half the battle. Before posting something you'd never say face-to-face, pause. Imagine saying it to the person in real life. If you wouldn't, don't hit send. This sounds simplistic, but it works - you're essentially manually engaging the empathy circuits that screens short-circuit.

Practice digital empathy. Assume good intent until proven otherwise. Remember that text lacks tone, and your interpretation might be wrong. When someone says something that makes you angry, consider that you might be misreading it - or that they're having the worst day of their life and lashing out, not targeting you specifically.

For parents and educators, teaching digital citizenship matters more than ever. Kids need to understand that online actions have real consequences, that pseudonymous accounts are still accountable, and that the person on the other side of the screen is, in fact, a person.

The key is awareness. Before posting something you'd never say face-to-face, pause and imagine saying it to the person in real life. You're manually engaging the empathy circuits that screens short-circuit.

Platform-level interventions are equally crucial. Implementing community moderation systems that empower users to flag content and sanction bad actors can preserve anonymity benefits while reducing toxicity. Reputation systems create accountability. Requiring "cooling off" periods before posting - imagine a 60-second delay before your tweet goes live - could reduce reactive hostility.

Design choices matter immensely. Platforms could reduce algorithmic amplification of outrage. They could default to chronological feeds instead of engagement-optimized ones. They could make blocking and filtering tools more robust. They could experiment with features that add friction to toxic behavior without censoring it - maybe requiring users to rewrite a comment flagged by AI as potentially hostile, adding a moment of reflection.

Online disinhibition is neither inherently good nor bad. It's a tool, and like all tools, its impact depends on how it's used.

The same digital distance that enables harassment also enables a teenager struggling with suicidal thoughts to reach out for help anonymously. The same lack of social cues that fosters trolling also lets people with social anxiety participate in communities they'd find overwhelming in person. The same platform that hosts hate speech also hosts support groups for rare diseases where patients who've never met in person save each other's lives with shared knowledge.

The question isn't how to eliminate online disinhibition - that would mean abandoning the internet's most powerful features. The question is how to tip the scales toward benign rather than toxic expression.

We're living through a massive social experiment. For the first time in human history, billions of people can communicate across vast distances with near-zero cost and minimal accountability. Evolution didn't prepare our brains for this. Our social instincts, our empathy, our capacity for shame and pride - all these evolved for small groups where reputation mattered and consequences were immediate.

Now we're trying to build functional societies in digital spaces where those old rules don't apply. The online disinhibition effect is the friction between our ancient social psychology and our modern digital reality.

The landscape continues to shift. As pseudonymity replaces full anonymity on many platforms, behavior changes - but not always in expected ways. Real-name policies don't automatically create civility. Durable pseudonyms sometimes work better than legal names. The mechanisms are more complex than "anonymity equals toxicity."

Emerging research continues to refine our understanding. Studies examining how revenge motivation interacts with toxic disinhibition reveal that individual psychological factors matter enormously. The same platform affects different people differently.

We're also beginning to understand protective factors. Consistent online self-presentation - maintaining a stable persona that aligns reasonably with your offline self - reduces engagement in controlling and aggressive behaviors. Building genuine community ties online can recreate some of the accountability that in-person relationships provide.

The future might involve AI moderators sophisticated enough to understand context and nuance, reducing the burden on human moderators who currently face serious mental health consequences from constant exposure to toxic content. It might involve new platform designs that we haven't imagined yet, systems that preserve privacy and freedom while creating meaningful accountability.

Or it might involve a cultural shift, a generation that grows up with better digital literacy and evolves new norms for online interaction. Maybe the answer isn't technological at all - maybe it's social, a collective decision to hold ourselves to different standards in digital spaces.

What's certain is that the online disinhibition effect will continue shaping how we communicate, organize, radicalize, support, connect, and clash. Understanding it doesn't make the problem go away, but it gives us the conceptual tools to navigate it thoughtfully.

The next time you see someone being terrible online - or catch yourself about to post something cruel - you'll know it's not just human nature. It's human nature colliding with a technology that bypasses millions of years of social evolution. And recognizing that might be the first step toward doing better.

Because the truth is, you're not actually meaner online. You're just more yourself, unfiltered by the social signals that usually keep the mean parts in check. The question isn't whether those parts exist - they do, in all of us. The question is whether we choose to feed them or starve them, one click at a time.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

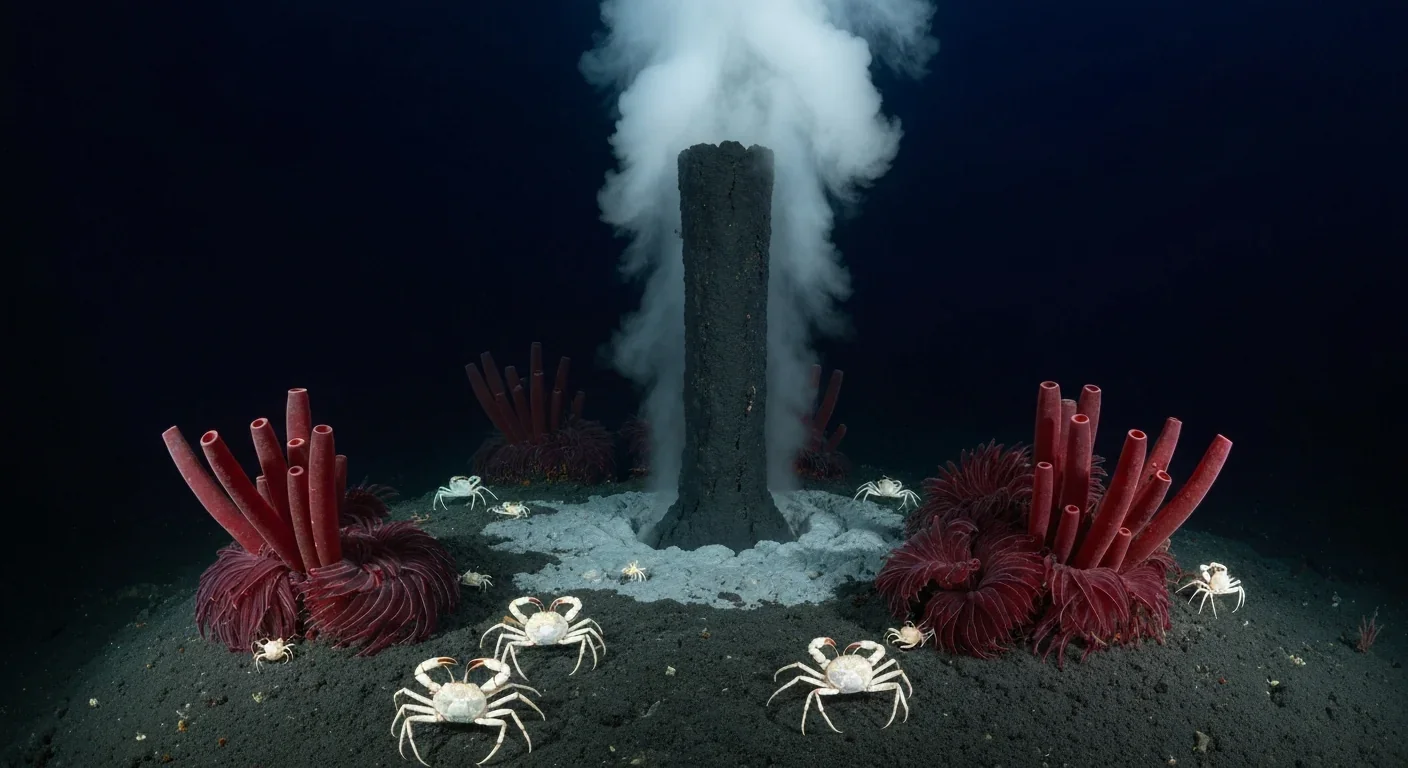

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.