Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Mate copying, the tendency to find already-chosen partners more attractive, is a scientifically documented phenomenon that operates across species. While the 'wedding ring effect' doesn't hold up in real-world interactions, research shows relationship experience does boost attractiveness, especially when conveyed through description rather than visual presence. The effect isn't gender-specific as once thought - both men and women use social proof to inform romantic choices, though context, culture, and individual differences modulate the strength of this evolutionary shortcut.

Sarah's friends thought she was crazy. Every time they went out, she found herself drawn to the guy with the wedding ring, the one who mentioned his girlfriend in passing, the man whose Instagram was full of couple photos. "I'm not a home-wrecker," she'd insist. "There's just something about them." Turns out, Sarah's not alone, and science has a name for what's happening: mate copying.

For decades, behavioral ecologists studying everything from guppies to grouse noticed something curious. Animals were making romantic decisions based on who others had already chosen. A female fish would ignore a perfectly good male until she saw another female showing interest, then suddenly he'd become irresistible. Researchers wondered: could humans be doing the same thing?

The answer is yes, though it's way more complicated than you'd think.

The mate copying story starts in aquariums, where scientists discovered that female guppies weren't actually picking mates based purely on bright colors or fancy fins. They were watching which males other females chose, then copying those choices. It made evolutionary sense because individual assessment is costly. If another female's already done the work of vetting a potential partner, why not benefit from her research?

Black grouse showed the same pattern. So did fruit flies, rats, and eventually, when researchers started testing humans, us too.

The breakthrough came when scientists moved beyond asking people to rate photos. In a landmark Swedish study, researchers had women interact with actual men, some wearing wedding rings and some not. The prevailing wisdom said married men would be rated as more attractive because the ring served as social proof of desirability.

The results? Women consistently said they'd rather have dinner with, sleep with, or start a relationship with the ringless men. The famous "wedding ring effect" didn't hold up in real interactions.

But before you dismiss mate copying entirely, here's where it gets interesting.

Mate copying is a form of non-independent mate choice where individuals use others' preferences as information about partner quality, an evolutionary shortcut that operates across species from guppies to humans.

When researchers showed women written descriptions of men with relationship experience, those men got higher attractiveness ratings. The boost was real and measurable. But when those same men were shown in photos standing next to their actual partners, the effect weakened or reversed entirely.

The key wasn't the wedding ring or relationship status itself. It was the information that someone else had already chosen this person, without the visual reminder that he's currently unavailable.

A 2009 study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found that when a man was merely described as being in a committed relationship, women's interest jumped from 59% to 90%. That's not a rounding error. That's a fundamental shift in perceived attractiveness triggered purely by social information.

Think about the last time you picked a restaurant in an unfamiliar city. Did you wander randomly, or did you check reviews and see where locals were eating? Mate copying works on the same principle: using social information as a shortcut to make better decisions.

From an evolutionary perspective, choosing a reproductive partner is one of the highest-stakes decisions an organism makes. Get it wrong and you've wasted time, energy, and genetic opportunity. In ancestral environments where you couldn't swipe through unlimited options or run background checks, watching who others chose provided valuable data about hidden qualities like reliability, resource-holding potential, and genetic fitness.

The biological mechanisms run deep. Studies with mice show that oxytocin, the hormone associated with social bonding, is critical for mate copying to work. Female mice with knocked-out oxytocin genes fail to recognize which male another female has chosen, and they don't copy mate choices. The behavior isn't just cultural. It's wired into mammalian neurobiology.

"Mate choice copying requires a highly developed form of social recognition by which the observer female recognizes the demonstrator female when mating with a target male and later recognizes the target male to mate with it."

- Behavioral Ecology Research

For years, the assumption was that mate copying was primarily a female phenomenon. Parental investment theory suggested women, who invest more in reproduction, would rely more heavily on social information to choose high-quality partners. Men, the thinking went, would care less about whether other women had pre-approved a potential mate.

Recent research challenges that narrative hard.

When scientists controlled for stimulus type and showed both men and women identical dating profiles from real speed-dating events, both sexes showed statistically significant mate copying effects of comparable magnitude. Men weren't immune to the phenomenon. They were just being tested differently in earlier studies.

The gender asymmetry that researchers thought they'd found was partly an artifact of experimental design. When you show men photos of women and women photos of men, you introduce confounding variables. When you level the playing field, both sexes use others' choices to inform their own preferences.

That doesn't mean the effect is identical across genders in all contexts. Some studies still find stronger copying effects in women, particularly in settings involving long-term relationship potential. But the idea that men don't engage in mate copying at all? That's been debunked.

Here's where theory crashes into messy reality. A TikToker decided to test the wedding ring theory by wearing a ring during a night out, expecting to attract more attention. He got drinks thrown at him. He got slapped. Twice. His conclusion: "Do not wear your wedding ring during the weekend if you're trying to have a good time."

The discrepancy between lab findings and bar experiences reveals something crucial about context. Mate copying isn't a simple on-off switch. It's modulated by a constellation of factors: the setting, the intentions people signal, the attractiveness of the current partner, and whether we're talking about brief interest or serious pursuit.

Research shows that relationship experience can boost perceived attractiveness, but the actual presence of a partner changes the calculation. When you see someone actively paired up, your brain doesn't just think "pre-approved." It also thinks "unavailable" and "potential drama." The social proof competes with practical and ethical barriers.

When a man was merely described as being in a committed relationship, women's interest jumped from 59% to 90%, demonstrating how powerful social information can be in shaping attraction.

One fascinating wrinkle: who the other woman is affects how much copying happens. If a highly attractive woman has chosen a man, observers rate him higher than if an average-looking woman chose him. The copier is essentially reasoning: "If she can get anyone she wants and she picked him, he must have something special."

This creates interesting dynamics in social hierarchies. A man's perceived value can shift dramatically based on his partner's attractiveness, independent of his own qualities. That's not entirely fair or logical, but mate copying was never about fairness. It's about information efficiency.

Before Instagram, you'd see someone's relationship status in limited contexts: at parties, through mutual friends, maybe a wedding announcement. Now every relationship is broadcast across platforms with photos, check-ins, and relationship status updates functioning as modern wedding rings.

Social media transforms mate copying signals from occasional encounters into constant ambient information. You don't just notice that Jake is in a relationship. You see him on vacation with someone gorgeous, at concerts, cooking dinner together, being demonstrably chosen by another person who displays their choice publicly.

Dating app designers understand this. Some platforms now include social proof features: showing you when someone you're interested in was recently liked by multiple people, or displaying mutual connections who endorse them. They're engineering mate copying into the matching process.

The digital age hasn't created mate copying, but it's amplified the signal and made it perpetually visible. Every couple photo is a billboard advertising someone's pre-screened status.

"Our results did not support the kind of sex difference expected by the received view. We did find evidence of human mate-choice copying, but both male and female participants changed their ratings in the direction of others' choices, and to comparable extents."

- Robert Bowers, HBES Research

Mate copying isn't uniform across cultures. In societies with different marriage norms, relationship timelines, and gender role expectations, the effect shows different patterns and intensities. Some cultures emphasize individual choice more heavily, potentially reducing reliance on social information. Others have stronger mate-guarding norms that make pursuing partnered individuals more taboo.

Individual personality also matters. People who are more conformist or uncertain about their preferences show stronger copying effects. Those with clear, stable attraction patterns are less swayed by others' choices. Attachment style, self-esteem, and relationship history all modulate how much we look to others when making romantic decisions.

This variation is important because it means mate copying isn't a universal law of human attraction. It's one strategy among many, deployed more or less depending on person and context.

Not everyone buys the mate copying story completely. When researchers tried to replicate the original guppy studies with more rigorous methods, some found no evidence of the effect. They concluded that mate copying might be population-specific or methodologically fragile, requiring careful experimental design to detect.

In humans, distinguishing mate copying from other explanations gets tricky. Maybe partnered people seem more attractive not because they've been chosen, but because they're more confident, more socially skilled, or displaying qualities that made them successful in relationships. The relationship status might be correlating with attractiveness rather than causing it.

Alternative explanations abound. Perhaps we're drawn to partnered people because they signal they can commit. Perhaps it's reactance, the forbidden fruit effect where unavailability makes someone more desirable. Perhaps women competing for male attention is less about mate quality assessment and more about social status competition between women.

Scientists continue debating which mechanisms explain what percentage of the effect. The picture is messier than any single theory suggests.

As many as one in five long-term relationships begin when one or both partners was already in a relationship, highlighting how mate copying and mate poaching interact in real-world dating dynamics.

So what does this mean for people navigating contemporary relationships? A few practical takeaways emerge from the research.

First, relationship experience isn't necessarily a red flag. Someone who's been chosen before has been, in evolutionary terms, "road-tested." That doesn't guarantee they're right for you, but it does suggest they possess qualities that at least one other person valued enough to commit to. The complete romantic novice at age 35 might warrant more scrutiny than someone with a relationship history.

Second, be aware that social proof affects your judgments in ways you don't always recognize. If you find yourself suddenly interested in someone the moment they post couple photos, ask whether you're responding to them or to the signal that someone else wants them. Your attraction might be genuine, but it's worth examining the timing.

Third, if you're partnered, understand that your relationship status broadcasts information about you whether you intend it to or not. Wedding rings, couple photos, and relationship mentions aren't neutral facts. They're social signals that affect how others perceive your attractiveness and availability. That's not a reason to hide your relationship, but it is worth being aware of the dynamics at play.

Finally, recognize that as many as one in five long-term relationships begin when one or both partners was already in a relationship. Mate copying and mate poaching are related phenomena. The same social information that makes someone attractive because they're chosen can motivate pursuit despite their unavailability. Navigating these dynamics ethically means distinguishing between appreciating that someone has qualities worth choosing and actively pursuing someone who's committed elsewhere.

Mate copying reveals something fundamental about human decision-making under uncertainty. We're social creatures who use others' choices as information shortcuts across countless domains. We eat at restaurants with lines, buy books that are bestsellers, watch shows everyone's talking about, and yes, find people more attractive when others have chosen them.

The behavior makes evolutionary sense because individual assessment is expensive and error-prone. Outsourcing some of that work to the collective intelligence of our social group is often adaptive. The person everyone wants probably has something valuable to offer, even if you can't immediately identify what it is.

But like all heuristics, mate copying can lead us astray. The most-chosen option isn't always the best option for you specifically. Someone else's perfect match might be entirely wrong for your personality, values, or life situation. Social proof is a starting point for investigation, not a conclusion.

Understanding mate copying lets you see your own attraction patterns more clearly. When you feel that pull toward someone who's already taken, you can ask: Am I responding to their actual qualities, or am I outsourcing my judgment to whoever got there first? Sometimes the answer is both. Sometimes it's worth examining whether you're letting others make decisions that should be yours alone.

The research continues to evolve. Scientists are investigating how digital platforms change mate copying dynamics, how cultural shifts affect the phenomenon, and whether the rise of non-traditional relationships changes how we interpret others' choices. What seemed like a simple observation in fish tanks turned into a complex story about human psychology, evolution, and the modern mating market.

Next time you catch yourself drawn to someone who's clearly taken, you'll know it's not just you being difficult. It's an ancient decision-making shortcut, playing out in contemporary contexts it was never designed for. Whether you listen to that signal or override it with other considerations is, ultimately, up to you. But at least now you know where it's coming from.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

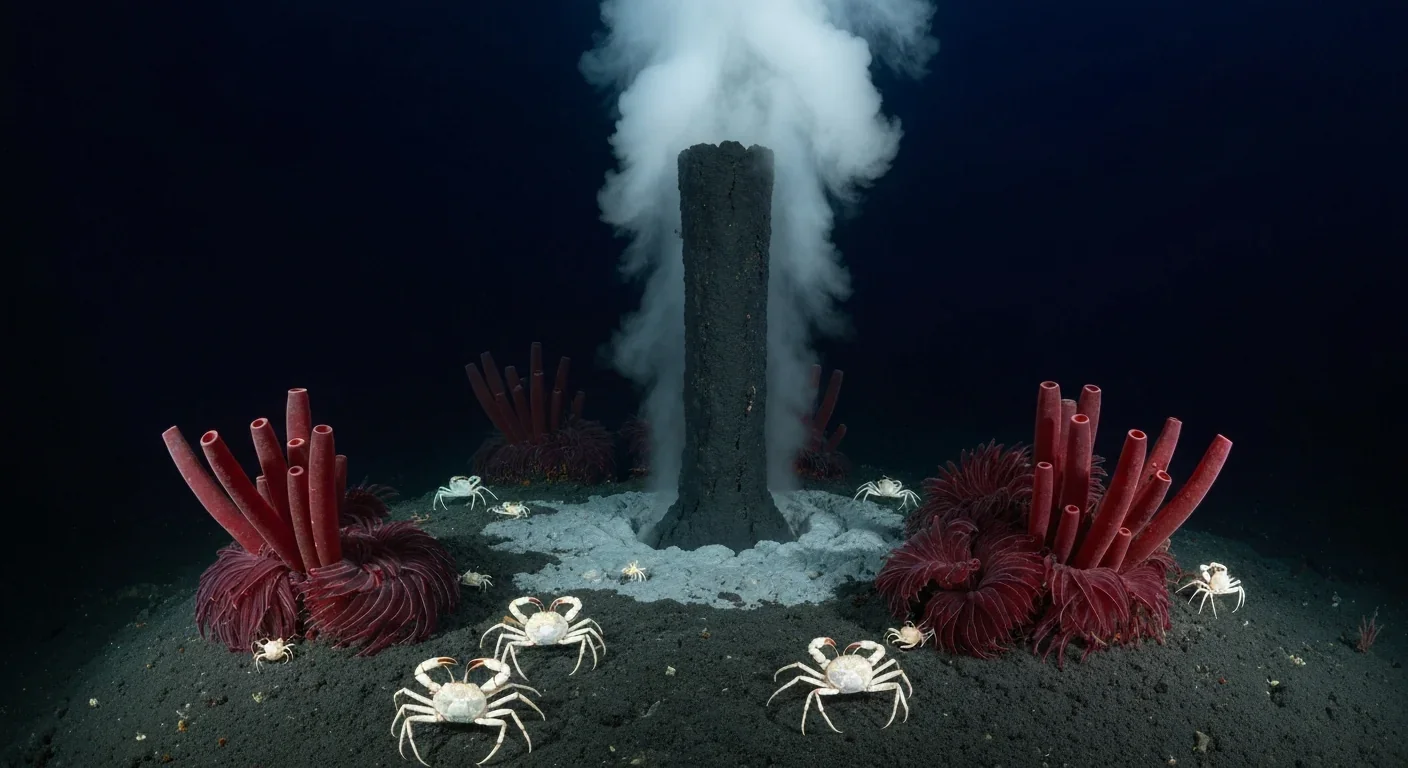

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.