Why Your Brain Erased Your First Years of Life

TL;DR: The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

Picture this: You walk into a psychology lab, flip a coin, get assigned to "Team A," and suddenly you want Team B to lose. You don't know anyone on either team. There's no prize for winning. Team A doesn't even exist outside this room. Yet something in your brain has already chosen sides.

That's the minimal group paradigm, and it's one of the most unsettling discoveries in social psychology. It shows that humans need almost no reason at all to start playing favorites and discriminating against "them" in favor of "us." What began as a simple experiment in the 1970s has revealed something fundamental about how our minds work and why we're so damn tribal.

In 1970, British psychologist Henri Tajfel was trying to figure out the absolute minimum conditions needed to create prejudice between groups. He gathered teenage boys and told them he was testing their ability to estimate dots on a screen. Then he split them into two groups supposedly based on whether they "overestimated" or "underestimated" the dots.

The grouping was completely random. The boys never met their teammates. They knew nothing about each other except a group label. Then came the resource allocation task: distribute points (worth real money) to other boys identified only by code number and group membership.

The result? Kids consistently gave more to their own group, even when doing so meant everyone got less money overall. They'd rather their group come out ahead than maximize everyone's gain. This wasn't supposed to happen. Tajfel expected to find the baseline level of zero bias, then add factors like competition or face-to-face interaction to see prejudice emerge.

Tajfel discovered that the baseline itself was biased. Give humans the thinnest possible reason to see themselves as "us" versus "them," and the favoritism switch flips automatically.

Instead, he discovered the baseline itself was biased. Give humans the thinnest possible reason to see themselves as "us" versus "them," and the favoritism switch flips automatically.

Since those first studies, the minimal group effect has been replicated hundreds of times across more than 20 countries. Researchers have used preferences for abstract paintings, random assignment by coin flip, colored T-shirts, even completely made-up group labels. Every time, the same pattern emerges: people favor their arbitrarily assigned in-group.

It works with children as young as three years old. It works across cultures from Japan to South Africa to Brazil. It works whether you're distributing money, praise, or punishment. The effect is so robust that it's become a standard tool for studying human bias because it isolates pure categorization from everything else.

What makes this particularly striking is what the paradigm deliberately excludes. There's no history of conflict between the groups. No competition over resources. No face-to-face interaction. No status hierarchy. Participants don't even benefit personally from favoring their group. The design strips away every rational reason for discrimination.

And discrimination happens anyway.

Social Identity Theory, developed by Tajfel and his colleague John Turner, explains what's happening in our heads during these experiments. The theory proposes that we don't just see ourselves as individuals; we see ourselves as members of groups. Those group memberships become part of our self-concept.

Here's the key mechanism: we boost our self-esteem by making our groups look good. If I'm part of Group A, and Group A is better than Group B, then by extension I'm better too. This need for "positive distinctiveness" motivates us to favor our in-group and, sometimes, to denigrate the out-group.

This isn't conscious calculation. It's automatic. Neuroscience research shows the brain categorizes faces as in-group or out-group within milliseconds, faster than we can consciously register what we're seeing. The fusiform face area and amygdala show different activation patterns when viewing in-group versus out-group faces, indicating that group membership processing is deeply embedded in our neural architecture.

"The brain discriminates between in-group and out-group faces within milliseconds, faster than conscious awareness."

- Neuroscience research on Social Identity Theory

We're not making a choice to be tribal. Our brains are doing it before we realize there's a choice to make.

Why would evolution wire us this way? Because for most of human history, your survival depended on knowing who was in your coalition and who wasn't. Our ancestors lived in small hunter-gatherer groups where distinguishing ally from stranger meant the difference between cooperation and conflict, sharing and starvation, safety and danger.

Evolutionary psychologists argue that our minds evolved specialized mechanisms for tracking coalitions, detecting free-riders, and coordinating group action. In ancestral environments, erring on the side of trusting your group and being wary of outsiders was adaptive. Those who failed to form strong group bonds or who were too trusting of strangers left fewer descendants.

The minimal group effect might be a byproduct of these ancient coalition-tracking systems. Our brains are so primed to form "us versus them" distinctions that even arbitrary modern labels trigger the same neural and behavioral responses that once helped our ancestors survive.

The problem is we're now living in a globalized world with our Paleolithic brains. The same mechanisms that helped small bands cooperate now generate prejudice against people who wear different sports jerseys or vote for different political parties.

Here's where it gets uncomfortable: if we're biased toward completely meaningless groups, what happens when groups actually matter? When they're tied to race, religion, nationality, political ideology?

The minimal group effect doesn't replace other forms of prejudice; it amplifies them. Research shows that arbitrary group assignments interact with existing social categories, making bias worse. If you already have implicit associations about race or gender, adding another layer of group identity on top intensifies the favoritism.

This helps explain political tribalism. Party affiliation has become a powerful group identity that shapes not just political views but also consumer choices, where people live, who they marry, and how they interpret reality itself. Studies show that group membership can be a stronger predictor of political behavior than individual policy preferences.

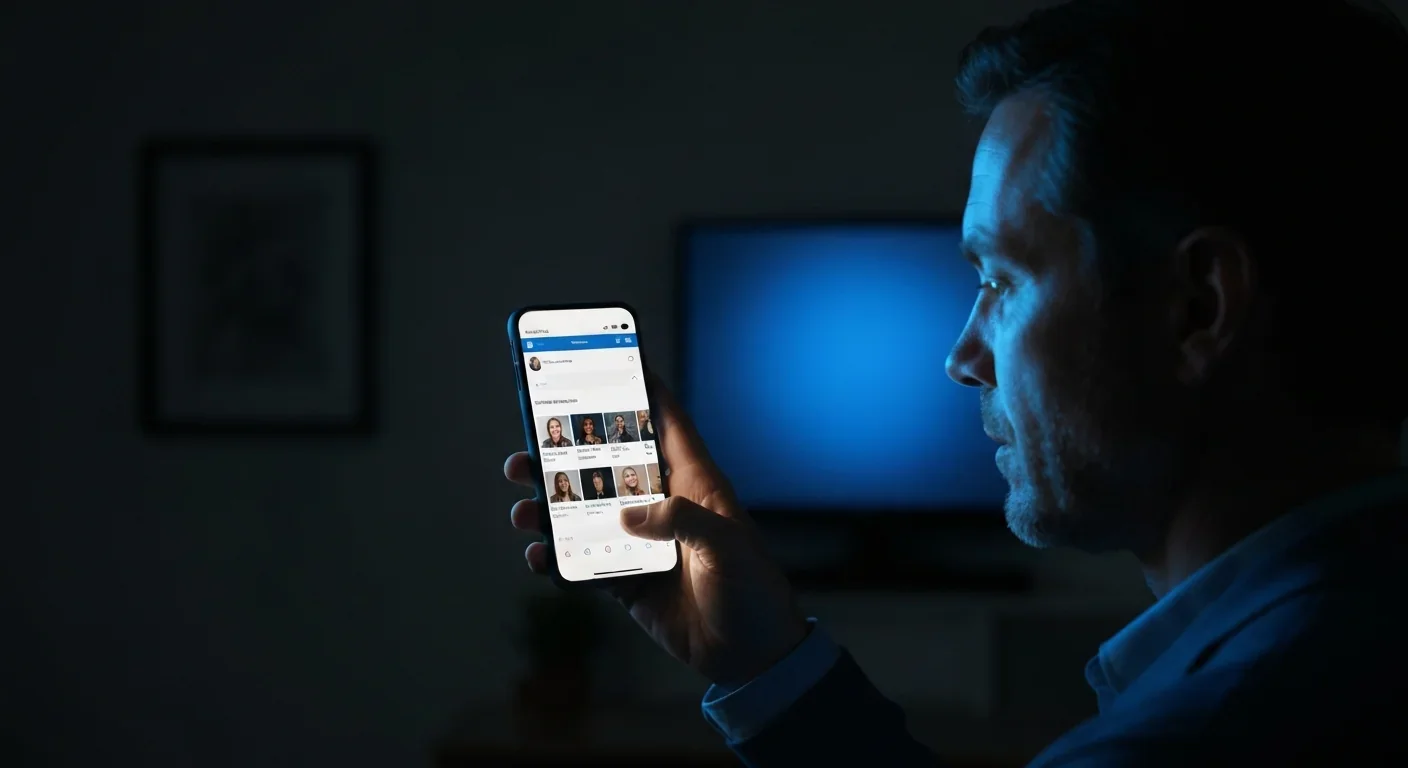

Social media algorithms create invisible minimal groups, sorting users by behavior and ideology - then feeding them content that reinforces tribal divisions without users even realizing they've been categorized.

The minimal group effect also illuminates online echo chambers. Social media platforms algorithmically sort users into groups based on behavior, interests, and demographics. These digital categories are often invisible to users, but they create the same in-group favoritism dynamics as lab experiments. You start seeing content from "your" group, which confirms your views, strengthens your group identity, and makes the out-group seem increasingly foreign and wrong.

Even brand loyalty follows this pattern. Apple versus Android, Nike versus Adidas, PlayStation versus Xbox - these are minimal groups with high emotional stakes. Marketers understand that creating a sense of tribal belonging around a product is more powerful than touting features or price.

One of the most sobering findings from neuroscience is just how quickly our brains make in-group versus out-group distinctions. Studies using fMRI and EEG show that the brain discriminates between in-group and out-group faces within 200 milliseconds, less time than it takes to blink.

This rapid processing happens in regions associated with emotion and social cognition, particularly the amygdala and fusiform face area. The speed of this categorization suggests it's not the result of deliberate reasoning but an automatic perceptual process, like recognizing a face as familiar or unfamiliar.

What's more, this quick categorization triggers downstream effects on empathy, trust, and moral judgment. People show less empathic neural responses when viewing out-group members in pain. They're quicker to attribute hostile intentions to out-group behavior. They're more likely to remember negative information about out-group members and positive information about in-group members.

All of this happens before conscious thought catches up. By the time you're aware you're forming an impression of someone, your brain has already filed them under "us" or "them" and adjusted your emotional and cognitive responses accordingly.

If you're hoping this is learned behavior that education can fix, the developmental research offers a reality check. Children as young as three to five years old show in-group favoritism when assigned to minimal groups.

Preschoolers given different colored shirts will preferentially share toys with same-color peers. Elementary school children assigned to arbitrary teams show the same resource allocation biases as adults in Tajfel's original experiments. The effect doesn't require cultural learning or adult modeling; it emerges spontaneously as soon as children can understand group categories.

This doesn't mean we're doomed to tribalism from birth. Developmental studies also show that children's group biases are malleable and influenced by how adults frame group identities. Kids whose teachers emphasize cooperation across groups show less favoritism. Children exposed to diverse groups early in life develop more flexible group boundaries.

But the underlying capacity for rapid group categorization and in-group preference appears to be part of human social cognition from early childhood. We're working with, not against, a fundamental feature of how developing minds make sense of the social world.

An important nuance often gets lost in discussions of the minimal group effect: in-group favoritism is not the same as out-group hostility. Most minimal group studies find that participants favor their own group rather than actively punishing the other group.

When given a choice between maximizing in-group gain or maximizing the difference between groups, people generally choose absolute gain for their group. They'll give their group more, but they're not going out of their way to hurt the other side. This is favoritism, not hatred.

"The minimal group effect reveals favoritism, not hatred - people boost their own group rather than actively punishing outsiders."

- Social psychology research findings

That said, the conditions that amplify minimal group effects can also tilt favoritism toward hostility. Competition over resources, perceived threats to the in-group, or emphasis on status differences can transform benign favoritism into active antagonism. The Robbers Cave experiment, conducted in 1954 with boys at summer camp, demonstrated how quickly group competition escalates to open conflict.

The practical implication is significant: reducing prejudice isn't just about suppressing negative attitudes toward out-groups. It also requires understanding why people are motivated to favor their in-groups and how to channel that motivation in less divisive directions.

The minimal group paradigm deliberately uses meaningless categories to isolate the effect of categorization itself. But in the real world, group categories are never meaningless. They carry historical baggage, power dynamics, stereotypes, and deeply personal significance.

Research examining how minimal group effects interact with real social categories like race and gender finds that arbitrary group assignments can either amplify or complicate existing biases. When people hold multiple group identities simultaneously, these identities intersect in complex ways.

For example, studies using an intersectionality framework show that someone might experience in-group favoritism based on race but out-group discrimination based on gender, with the two identities shaping behavior differently depending on context. The minimal group effect doesn't erase real-world prejudice; it adds another layer to an already complicated picture.

This complicates interventions. You can't just eliminate group categories and expect bias to disappear, because people will generate new categories to replace them. And some group identities are deeply meaningful and shouldn't be erased - they're sources of community, culture, and pride.

So what works? Decades of research on prejudice reduction offer some evidence-based strategies, though none are magic bullets.

Recategorization involves creating a superordinate identity that encompasses both groups. The Common In-group Identity Model shows that when you get people to see themselves as part of a larger "we," bias between subgroups decreases. This is why emphasizing shared humanity, common goals, or organizational identity can reduce team-based conflicts.

Cross-group contact under the right conditions reduces prejudice. The key conditions are equal status between groups, common goals, cooperation rather than competition, and institutional support. Contact alone isn't enough - throwing hostile groups together can make things worse - but structured positive contact changes attitudes.

Perspective-taking exercises that encourage people to imagine the world from an out-group member's viewpoint reduce bias. Even simple interventions like reading stories from out-group perspectives or playing cooperative games with diverse partners show measurable effects.

Understanding that our brains automatically categorize and favor in-groups can motivate people to consciously check those impulses - creating space for reflection before acting on tribal instincts.

Making group boundaries flexible helps. When people understand that group memberships are fluid rather than fixed, they show less rigid favoritism. Highlighting ways people belong to multiple overlapping groups reduces the psychological power of any single us-versus-them division.

Awareness itself has some value. Understanding that our brains automatically categorize and favor in-groups can motivate people to consciously check those impulses. This doesn't eliminate automatic biases, but it creates space for reflection before acting on them.

The minimal group paradigm has profound implications for how organizations function. Companies often create arbitrary internal divisions - departments, office locations, project teams, tenure levels - without realizing these divisions can generate the same biases as lab experiments.

When the marketing team sees itself as fundamentally different from engineering, or when remote workers form an identity separate from office workers, you get the minimal group effect at organizational scale. People compete for resources, attribute problems to other departments, and interpret ambiguous situations through the lens of team loyalty.

Smart organizational design accounts for this. Rather than trying to eliminate all group distinctions (which is impossible and often counterproductive), effective leaders create overlapping group memberships, rotate people across teams, emphasize organization-wide goals, and build structures that require cross-group cooperation.

Diversity and inclusion initiatives that simply celebrate different group identities without creating meaningful integration can inadvertently strengthen group boundaries. The goal shouldn't be colorblindness or pretending differences don't exist, but rather creating conditions where multiple identities can coexist without triggering zero-sum competition for status and resources.

If you want to see the minimal group effect on steroids, look at social media. Platforms use algorithms to group users in ways that are often invisible but psychologically powerful. You're sorted by engagement patterns, ideological leanings, demographics, and behavior, then fed content that reinforces your group's worldview.

These algorithmically-created groups function like minimal groups, except instead of random assignment, you're categorized by sophisticated machine learning based on billions of data points. The result is the same: in-group favoritism, out-group suspicion, and reinforcement loops that make group boundaries feel increasingly natural and important.

The recommendation algorithms aren't neutral. They optimize for engagement, which means showing you content that confirms your existing beliefs and triggers emotional responses. This creates what researchers call "filter bubbles" or "echo chambers" - information environments where you primarily encounter perspectives from your own group.

What makes this particularly insidious is that users often don't realize they're in a minimal group. There's no explicit label saying "you've been assigned to Political Tribe A." The grouping happens in the background, shaping what you see and therefore what you think everyone else sees, creating parallel realities.

Breaking out of digital echo chambers requires conscious effort: seeking out diverse information sources, engaging with people who disagree, questioning the algorithms that curate your feed. But these strategies work against the grain of both platform design and human psychology.

Cross-cultural research on the minimal group effect reveals both universals and variations. The basic phenomenon replicates worldwide, but the magnitude and specific expression vary across cultures.

Studies in collectivist societies sometimes show stronger in-group favoritism because group identity is more central to self-concept in those cultures. However, some collectivist cultures also show more sensitivity to fairness norms that can moderate bias. Individualist societies may show weaker group effects in lab settings but stronger real-world tribalism in domains like politics and sports.

The implications for global cooperation are sobering. If humans everywhere are predisposed to favor arbitrary in-groups, then building institutions that transcend national, ethnic, and religious boundaries requires swimming against a cognitive current. Yet we've done it before.

International scientific collaboration, global trade networks, and multinational organizations all demonstrate that humans can construct identities and loyalties beyond their immediate tribes. The challenge is scaling those successes while acknowledging rather than denying the psychological barriers.

The minimal group paradigm isn't just an academic curiosity. It's a mirror showing us something uncomfortable about human nature: we're all capable of bias based on nothing at all.

This doesn't mean we're doomed to prejudice. Understanding the mechanism is the first step toward managing it. When you catch yourself feeling loyalty to a brand, defensiveness about a political position, or unearned pride in a random team assignment, you're witnessing your own minimal group psychology in action.

The practical takeaway is humility. If teenage boys will discriminate based on made-up dot estimation groups, then all of us are vulnerable to tribalism in more consequential domains. The in-group favoritism you feel for your political party, your alma mater, your city, your nation - some of that is the same arbitrary group bias playing out with higher stakes.

Recognizing this doesn't make the feelings go away, but it creates psychological distance. You can appreciate group belonging without assuming your group is objectively superior. You can feel team loyalty without demonizing the other side. You can acknowledge that much of what feels like meaningful group identity is the brain's coalition-tracking software running on modern inputs it wasn't designed for.

The minimal group paradigm teaches us that the roots of prejudice aren't just in hate or ignorance. They're in the basic architecture of human social cognition, in the way we automatically and inevitably carve the social world into "us" and "them." Understanding that is unsettling. It's also liberating, because it shifts the question from "why are those people biased?" to "how do we all work with the biased brains we have?"

And maybe that's a question we can answer together - as one group.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

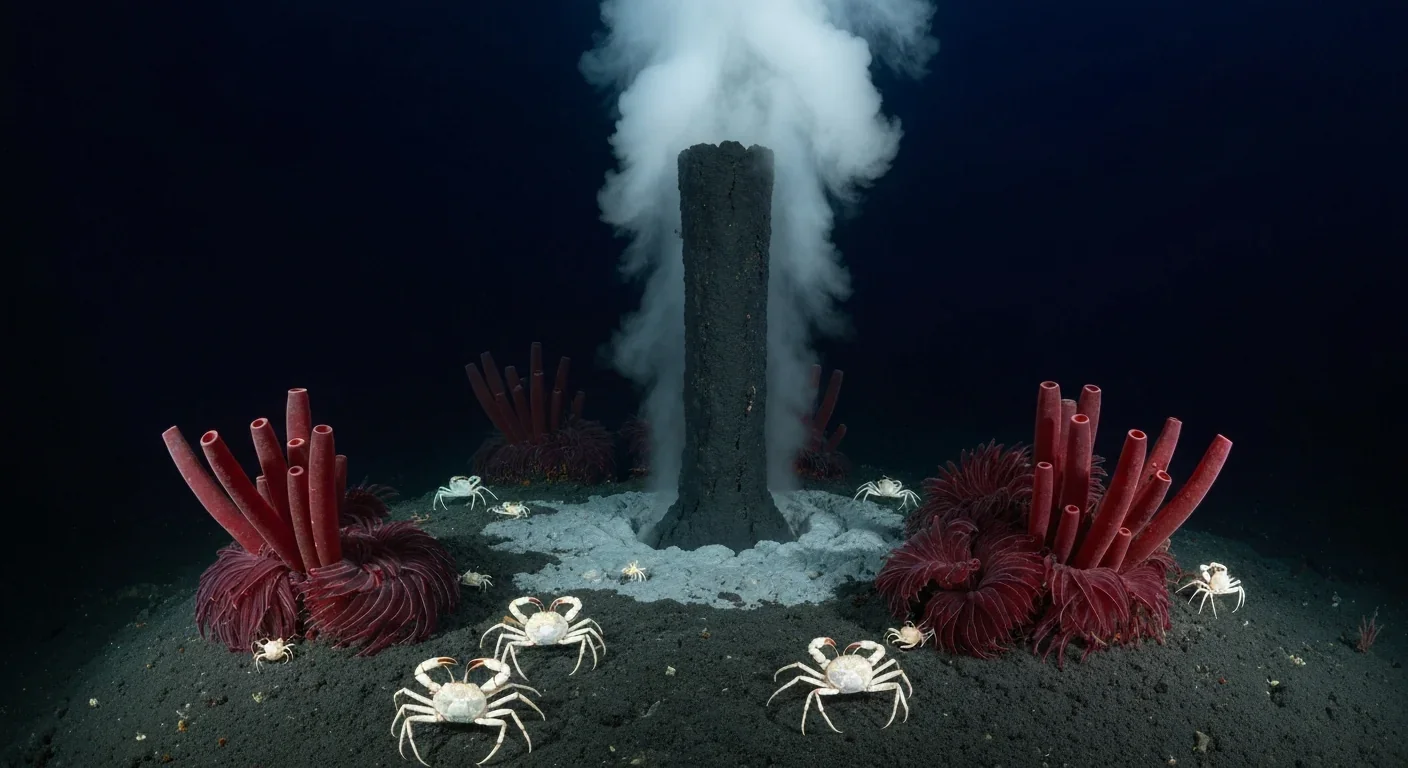

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.