Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Your brain constantly judges things by comparison, not absolute value - and this contrast effect systematically distorts every decision you make. From retail pricing tricks to performance reviews to self-worth spirals, understanding how reference points control perception is the first step toward resisting manipulation.

Your brain is lying to you right now.

Not in an obvious way. It's not hallucinating or malfunctioning. It's doing exactly what evolution designed it to do - making sense of the world through comparison. The problem? Those comparisons are systematically distorting almost every judgment you make, from what you buy to whom you find attractive to how you value yourself.

This is the contrast effect: a cognitive bias where perception of value, attractiveness, and quality depends heavily on what you're comparing it against rather than any absolute standard. It's so pervasive that once you see it, you'll spot it everywhere - and realize how often you've been manipulated by it.

Think you evaluate things on their own merits? Consider this: the same gray square looks dramatically lighter on a black background than on white. The same lukewarm water feels scalding hot if your hand was just in ice water, pleasantly warm if it came from a hot bath. John Locke noticed this in the 17th century, but we're still falling for it today.

The effect extends way beyond sensory perception. In a classic psychology experiment, participants rated the same person's attractiveness differently depending on who they'd seen immediately before. After viewing highly attractive faces, average faces seemed less appealing. After unattractive faces, those same average faces looked better. The faces didn't change - the context did.

This isn't a quirk of how we see colors or faces. It's fundamental to how our brains process information across every domain: prices, salaries, performance reviews, romantic partners, even our own self-worth. We're comparison machines, and we're terrible at recognizing when those comparisons are being deliberately manipulated.

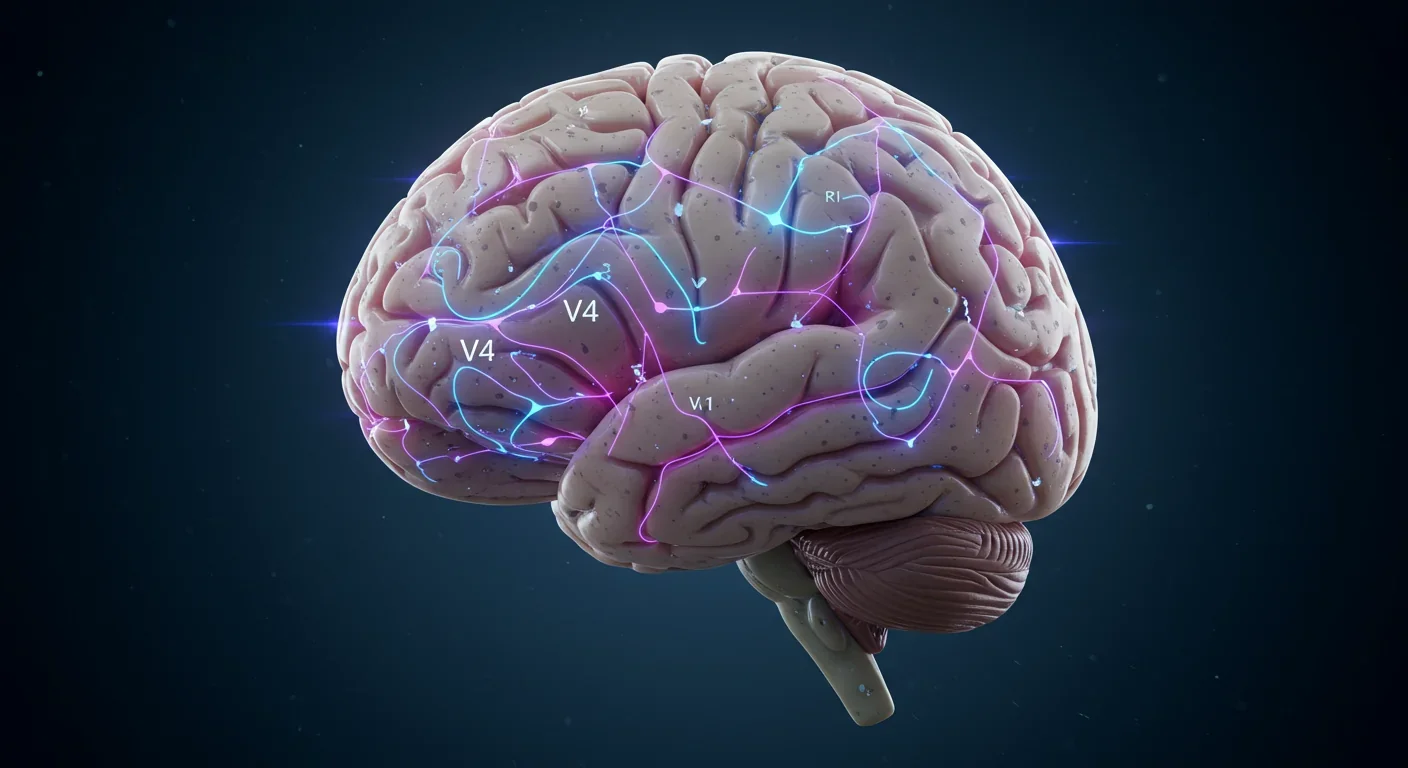

The neurological basis involves inhibitory connections among neurons in the visual cortex, particularly the V4 area. When you look at something, neighboring neurons suppress each other's activity, amplifying differences and creating sharper contrasts. This edge-detection system helped our ancestors spot predators hiding in grasslands.

But what worked for survival created a systematic flaw in modern decision-making. Your brain doesn't encode absolute values - it encodes relative ones. Show someone a $50 wine, and they'll judge it one way. Show them a $200 wine first, and suddenly that $50 bottle looks like a bargain. The wine's quality hasn't changed, but the reference point has.

Your brain doesn't calculate absolute worth. It asks: "Compared to what?"

Cognitive psychologists have identified this as part of dual-process thinking. The fast, intuitive System 1 relies heavily on contextual cues and comparisons. The slow, analytical System 2 can override this bias - but only when you're aware of it and actively engaged. Most of the time, you're running on autopilot, vulnerable to whatever comparison your environment presents.

Walk into Williams-Sonoma and you'll see a $275 bread maker sitting next to a $429 model. The expensive one barely sells. That's not the point. According to research from Harvard's Program on Negotiation, after the $429 model appeared, sales of the $275 version nearly doubled. Customers didn't suddenly need bread makers more - they just needed something worse to compare against.

This is decoy pricing, and it's everywhere. The medium popcorn at a movie theater costs $7. The large costs $7.50. Nobody buys medium until they see the small costs $6.50. Suddenly medium looks like the smart choice, even though you didn't want popcorn at all five minutes ago.

Research shows decoy pricing can increase purchase probability by 30-45% in grocery stores and online marketplaces. The decoy doesn't need to sell - it just needs to make something else look better by comparison. You think you're making a rational choice. You're actually responding to a carefully constructed reference point.

Real estate agents play the same game. They'll show you overpriced, run-down properties first, then present ordinary homes that suddenly appear stunning. The houses haven't changed quality. Your comparison standard has been reset.

The contrast effect doesn't just manipulate what you buy - it shapes whom you're attracted to and how you judge others' appearance. The "cheerleader effect" demonstrates this beautifully: people appear 1.5-2.0% more attractive in group photos than alone.

Why? When you see a group, your brain creates ensemble representations - averaging features rather than processing each face individually. Since attractive faces tend to be close to average (more symmetrical, fewer unusual features), this averaging makes everyone look slightly better.

"Humans tend not to process every individual detail they perceive. Instead of devoting attention to all characteristics, our brain quickly summarizes the information as a group."

- Psychology researchers studying visual perception

But there's a twist. Present faces simultaneously, and you get this averaging effect. Present them sequentially - one after another - and you get pure contrast. An attractive face makes the next one seem worse; an unattractive face makes the next seem better. Dating apps know this. That's why swiping through profiles feels so volatile - your standards are constantly recalibrating based on the last person you saw.

Research confirms this isn't superficial vanity. It's deep cognitive architecture. Studies show the effect persists regardless of presentation time - brief glimpses produce the same distortion as longer viewing. Your brain is making these comparative judgments automatically, before conscious thought kicks in.

The workplace is a minefield of contrast effects. Performance reviews should evaluate employees against objective standards. Instead, managers unconsciously compare workers to each other, creating what HR professionals call "contrast bias."

If you're reviewed right after a superstar colleague, you look worse - even if your actual performance hasn't changed. If you follow someone struggling, you look better. The bias is strong enough that HR experts recommend using clear performance standards that apply equally to all employees, specifically to counteract this effect.

Hiring suffers the same problem. Interview five mediocre candidates, and the sixth merely okay candidate looks stellar. Interview two excellent candidates first, and that same sixth person looks inadequate. Professional evaluators fall for this even when they know about the bias.

Contrast bias in performance reviews can skew promotions, compensation, and career trajectories based purely on evaluation order - not actual merit.

The implications ripple through entire organizations. Promotions go to people reviewed in favorable sequences. Salary negotiations succeed or fail based on what reference points the other party is using. Team assignments reward or punish based on arbitrary comparisons rather than objective capability.

Understanding the contrast effect transforms how you approach any negotiation. The classic strategy: ask for more than you expect, get rejected, then lower your offer. Your counterpart finds the second offer more reasonable - not because it's objectively fair, but because it's smaller than the first.

This is anchoring meets contrast effect. The initial high number sets a reference point. The subsequent lower number feels like a concession, like progress, like reasonableness - even if it's still far above what you would have accepted at the start.

Real estate agents, car salespeople, and professional negotiators deploy this constantly. The first number mentioned disproportionately influences the final agreement, regardless of its relationship to actual value. Studies show that even when people know about anchoring, they still can't fully resist it.

The defensive move: establish your own reference points first. In job interviews where you lack information about the salary range, you're vulnerable to whatever anchor the employer sets. If you have superior information - say, industry salary data - you can set an anchor that works in your favor. Information asymmetry determines who controls the reference frame.

Research on professional real estate agents showed that giving them different listing prices for the same house led to 12-15% differences in their valuations - professionals who should know better. The anchoring effect was proportional to how far the anchor diverged from actual market value.

Perhaps the most insidious application of the contrast effect is how it shapes self-perception. Your sense of your own attractiveness, intelligence, success, or worth depends heavily on whom you're comparing yourself against.

Scroll through Instagram and you're comparing your behind-the-scenes to everyone else's highlight reel. Work at a company full of brilliant people and you feel inadequate, even if you'd be the star performer elsewhere. This isn't impostor syndrome exactly - it's your brain doing what it evolved to do, measuring relative position rather than absolute capability.

Hedonic adaptation compounds this. You get a raise, and for a week you feel wealthier. Then you adapt to the new baseline and need another raise to feel that boost again. The money hasn't lost value, but your reference point shifted. Research shows emotional well-being peaks around $60,000-$75,000 annually, then declines as income rises further - partly because higher earners compare themselves to even wealthier peers.

The social comparison never stops. Move to a nicer neighborhood, and suddenly your adequate house feels small because you're comparing it to neighbors' mansions instead of your old apartment. Get promoted, and suddenly you're the junior person among senior executives instead of the senior person among mid-level employees. The treadmill keeps running because the reference point keeps shifting.

How information is framed determines how you perceive it, and framing is fundamentally about creating implicit comparisons. Tell someone a medical treatment has a "95% survival rate" and they're more likely to choose it than if you say it has a "5% mortality rate" - even though the statistics are identical.

The classic Asian disease problem demonstrated this perfectly. Present options framed as saving lives, and 72% of people chose the certain option. Frame the same choice as preventing deaths, and 78% chose the risky option. The outcomes hadn't changed. The reference frame had.

Marketers weaponize this constantly. A phone battery "retains 95% charge!" sounds better than "loses 5% charge," despite describing the same product. During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers found that framing effects increased decision bias by up to 20 percentage points in high-stress conditions - precisely when people most needed clear thinking.

"People are more vulnerable to framing effects when relying on the intuitive system, as it is more susceptible to contextual cues."

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

Political pollsters understand this deeply. Ask "Do you support reducing wasteful government spending?" and you'll get very different results than "Do you support cutting government programs?" The policy is the same. The implicit comparison - waste versus programs - completely changes perception.

Sometimes comparison creates the opposite effect. Instead of contrast, you get assimilation - where your judgment pulls toward the comparison standard rather than away from it.

The difference depends on how you mentally categorize the comparison. If you see it as part of the same category, assimilation happens. If you see it as separate, contrast happens. Ask people about their dating satisfaction, then ask about overall life satisfaction, and the second answer assimilates toward the first. The specific question sets a frame that carries forward.

Weather forecasts demonstrate this beautifully. If forecasters predict 24°C and it's actually 22°C, you feel pleasantly comfortable - the day assimilated toward the moderate prediction. If they predict 35°C and it's 22°C, you feel noticeably cool - the contrast between expectation and reality dominates your perception.

The inclusion/exclusion model explains when you get which effect. Include the comparison in your mental representation of the target, and assimilation occurs. Exclude it as a separate reference point, and contrast dominates. Marketers and politicians manipulate this boundary constantly, framing their preferred options as part of your in-group while positioning alternatives as outsiders.

Older adults show stronger negative framing effects than younger people, likely because aging reduces analytical processing capacity and increases emotional arousal. This makes elderly people particularly vulnerable to manipulative framing in financial decisions, medical choices, and political messaging.

Cultural differences matter too. While the basic contrast effect appears universal - it's rooted in fundamental neurology - how strongly it manifests and which domains it affects most vary across cultures. Individualistic societies may show stronger contrast effects in personal attractiveness judgments, while collectivist cultures might display it more in group performance evaluations.

Professional expertise doesn't immunize you. Remember those real estate agents whose valuations shifted 12-15% based on arbitrary listing prices? Awareness helps but doesn't eliminate the effect. Even researchers who study these biases fall victim to them in everyday decisions.

Can you escape the contrast trap? Partially. Complete immunity is impossible - the effect operates at a neurological level below conscious awareness - but you can reduce your vulnerability.

Strategy 1: Recognize the setup. When you encounter extreme options - the overpriced menu item, the terrible house shown first, the unreasonable initial offer - realize someone is likely setting an anchor to make something else look better by comparison. Ample credible information reduces framing effects, so seek objective data before deciding.

Strategy 2: Establish your own reference points. Before negotiating salary, research industry standards. Before buying, determine what you're willing to pay based on absolute value, not relative positioning. The more informed you are, the less vulnerable you are to manipulated comparisons.

Information asymmetry determines who controls the reference frame in any negotiation or purchasing decision.

Strategy 3: Use absolute standards when possible. Performance reviews should measure against predetermined criteria, not against other employees reviewed that week. Purchasing decisions should reference objective needs, not whatever options happen to be presented together. Create systems that force absolute evaluation before allowing comparison.

Strategy 4: Delay decisions after exposure to extremes. If you just saw a high-priced option or an exceptionally attractive person or a stellar job candidate, your judgment of the next option will be distorted. Wait. Let the reference point fade before evaluating the next choice.

Strategy 5: Engage System 2 thinking. Analytical processing reduces susceptibility to framing. When making important decisions, force yourself to analyze rather than relying on intuitive judgments. Write out pros and cons. Calculate expected values. Anything that slows you down and engages deliberate reasoning helps.

The depressing reality is that contrast effects are everywhere, all the time. You can't escape them because they're baked into how perception works.

Product lines are structured around them. The luxury item exists to make the premium item look affordable. The basic tier exists to make the standard tier look feature-rich. Nobody expects you to buy the extreme options - they exist to manipulate your perception of the middle.

Social media feeds are contrast engines. Every photo you scroll past resets your standard for beauty, success, travel, parenting, cooking, fitness. The infinite stream prevents you from ever establishing a stable reference point. You're always comparing against something, and that something is always curated to look better than reality.

Dating apps systematically reset your standards with every swipe. Someone who would have seemed attractive after viewing five profiles looks mediocre after viewing fifty. The apps aren't showing you objectively different people - they're changing your reference frame through sheer volume of exposure.

Even your life satisfaction operates on contrast. Move from a studio apartment to a one-bedroom, and you feel richer. Six months later, you've adapted and the one-bedroom feels normal. The hedonic treadmill is fundamentally a series of shifting reference points, each new achievement becoming the baseline for the next comparison.

We can't rewire our brains to stop making comparisons. Nor would we want to - relative judgment is computationally efficient and usually useful. The problem isn't that we compare. It's that we're unaware we're comparing, so we mistake relative judgments for absolute ones.

The next decade will likely see increased sophistication in contrast manipulation. AI-powered recommendation systems will learn exactly which reference points most effectively shift your preferences. Personalized pricing will anchor based on your individual purchase history and browsing behavior. Virtual reality might let marketers control your entire visual context before presenting a product.

But the same technology that enables manipulation could enable resistance. Imagine browser extensions that flag decoy pricing, apps that provide objective reference data before negotiations, or AI assistants that analyze whether you're being anchored. The tools to counter contrast effects could scale as fast as the manipulation itself.

The future won't eliminate the contrast effect - it's neurologically hardwired. But awareness is the first step toward agency in a world designed to control your reference points.

In the meantime, the most practical response is epistemic humility. When you judge something as expensive, attractive, impressive, or disappointing, add a silent qualifier: "Compared to what?" That simple question won't eliminate the bias, but it might make you pause long enough to recognize when your perception is being deliberately manipulated.

Your brain will keep comparing. It can't help it. The question is whether you'll notice when someone else is choosing what you compare against - and whether you'll choose to resist.

The contrast effect doesn't make you irrational. It makes you human. The goal isn't to transcend your cognitive architecture. It's to understand it well enough that you can tell the difference between seeing clearly and seeing through a carefully constructed filter.

Because right now, in ways you're barely aware of, your reality is being rewritten by whoever controls your reference points. And until you see the comparisons shaping your perception, you can't begin to question whether they're serving you - or someone else.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.