Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: The outgroup homogeneity effect makes us see other groups as identical while viewing our own as diverse. This cognitive bias stems from evolutionary survival instincts and brain shortcuts, affecting everything from hiring decisions to criminal justice. Understanding and countering it requires awareness, structural changes, and sustained effort.

Walk into any contentious meeting - a tense negotiation, a heated political debate, a diversity workshop gone sideways - and you'll hear variations of the same sentiment: "They just don't get it." Not "some of them" or "a few individuals in that group," but a sweeping they, as if millions of people share one brain. This isn't just sloppy language. It's a cognitive bias so deeply wired into human perception that it shapes everything from workplace hiring decisions to courtroom eyewitness testimony to why your uncle insists all millennials are entitled. Psychologists call it the outgroup homogeneity effect, and it's the reason we see "them" as identical while viewing "us" as wonderfully diverse.

The stakes aren't trivial. When a recruiter reviews a stack of resumes, the outgroup homogeneity effect can make candidates from underrepresented backgrounds blur together into generic stereotypes while in-group applicants stand out as unique individuals. When police officers identify suspects across racial lines, this bias contributes to higher rates of misidentification, with innocent people sometimes imprisoned because "they all looked the same" to a witness. In our increasingly tribal political landscape, the effect fuels polarization by flattening the opposition into a monolithic enemy rather than a coalition of people with varying beliefs.

Your brain receives roughly 11 million bits of sensory information every second, but your conscious mind can process only about 40. To cope with this torrent, your neural circuitry relies on shortcuts - heuristics that help you navigate the world without melting down from cognitive overload. One of those shortcuts is categorization: sorting people, objects, and experiences into mental bins labeled "like me" and "not like me."

This sorting happens fast. When you encounter someone from your own group - however you define that group, whether by race, profession, political party, or hometown - your brain automatically engages in what psychologists call individuated processing. You notice details: the way they gesture when they talk, their specific opinions on various issues, the quirks that make them them. You encode this information richly because you expect to interact with this person again, because their behavior might affect you, or simply because your brain has learned to pay attention to people who resemble you.

But when you encounter someone from an outgroup? Your brain switches to category-based processing. Instead of encoding individual features, you file the person under a general label: "Democrat," "boomer," "tech bro," whatever fits. Research shows that participants remember specific behaviors of ingroup members while remembering outgroup members more generically - if they remember them at all. In recognition tasks, people excel at distinguishing faces from their own racial or social groups while struggling to tell apart faces from other groups, the well-documented cross-race effect.

The diversity within outgroups is real - your brain just isn't bothering to encode it. Category-based processing smooths individual variation into perceived uniformity.

The result? Outgroups appear homogeneous because your brain literally isn't bothering to encode the differences. The diversity is there in reality, but your perception has smoothed it into uniformity.

The evolutionary story behind this bias makes uncomfortable sense. For most of human history, your survival depended on knowing who belonged to your tribe and who didn't. Early humans lived in small groups that competed with other groups for limited resources like food, water, and territory. In that context, quickly identifying "us versus them" wasn't just useful - it was life or death.

Your ancestors who excelled at ingroup favoritism and outgroup caution passed on their genes. Those who failed to distinguish friend from foe, or who extended too much trust to outsiders, often didn't live long enough to reproduce. The neural architecture that supported rapid us-them distinctions became hardwired into our species. Today, your amygdala - the brain's threat-detection center - still activates more strongly when you view faces from outgroups, especially groups portrayed negatively in your environment.

A fascinating 2006 neuroimaging study by Harris and Fiske found that when participants viewed images of extreme outgroups, there was reduced activation in the medial prefrontal cortex, a region involved in complex social cognition and thinking about other people's minds. Instead, the brain showed increased activation in the insula and amygdala, areas associated with disgust and threat detection. In other words, under certain conditions, our brains can process outgroup members less like people with inner lives and more like objects or threats.

"When participants viewed images of extreme out-groups, there was a lack of activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is typically involved in social cognition. Instead, there was increased activation in the insula and amygdala, areas associated with disgust."

- Harris & Fiske, 2006

But here's where the evolutionary explanation gets tricky. While our ancestors lived in stable tribes of 50 to 150 people, modern life constantly throws us into contact with thousands of strangers from countless backgrounds. The cognitive tools that kept small groups cohesive now drive us apart in a globalized world. We're operating with Paleolithic brains in a cosmopolitan era.

The outgroup homogeneity effect isn't a single bias but rather the output of several cognitive processes working in concert. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why the bias is so stubborn and pervasive.

Differential encoding and retrieval: You simply have more experiences with ingroup members, and each experience adds nuance to your mental representation. If you're a software engineer, you've probably worked with dozens or hundreds of other engineers, each with distinct coding styles, communication preferences, and personality traits. But if you rarely interact with, say, ballet dancers, your mental file labeled "ballet dancers" remains sparse, populated mostly by stereotypes from movies and casual observations. The more contact you have with a group, the more likely you are to recognize individual variation.

Cognitive miserliness: Your brain is lazy (technically, it's efficient). Thinking deeply about every person you encounter would exhaust your cognitive resources, so your brain defaults to categorical thinking when it can get away with it. With ingroup members, social norms and repeated interactions force you to expend the effort. With outgroup members, there's less social pressure to individuate, so your brain sticks with the low-effort stereotype.

Essentialist thinking: Humans have a tendency to believe that categories reflect deep, inherent essences rather than superficial or constructed boundaries. When you see a group as defined by an unchanging essence, you naturally expect all members to share core characteristics. Research on entitativity - the perception that a group is a unified entity - shows that when people view a collection as highly cohesive, they attribute universal characteristics to all members, reinforcing the homogeneity effect.

Limited cognitive resources under stress: When you're stressed, tired, or cognitively overloaded, your brain relies even more heavily on stereotypes. A manager making hiring decisions at the end of a long day is more likely to fall back on categorical judgments than one who's well-rested and focused. This is why structural interventions like blind resume screening can be more effective than simply asking people to "try harder" not to be biased.

The outgroup homogeneity effect isn't just an academic curiosity. It shapes outcomes in domains that determine people's life chances and safety.

In the criminal justice system, the bias contributes to wrongful convictions. Eyewitness misidentification is a leading cause of wrongful imprisonment, and cross-race identification errors are significantly more common than same-race errors. When a witness says "I'm certain that's the person," they might genuinely believe it, unaware that their brain processed the suspect's face through a categorical rather than individuated lens.

In hiring and promotion, the effect makes outgroup candidates seem interchangeable while ingroup candidates appear distinctive. A 2017 meta-analysis found that when evaluators viewed resumes with identical qualifications, they rated ingroup members as more competent and memorable. The result is workplace homogeneity that organizations claim they want to fix but unconsciously perpetuate.

In political polarization, the bias makes compromise nearly impossible. If you perceive the opposing party as a uniform bloc with identical extreme views, why bother seeking common ground? Research on partisan polarization shows that people dramatically overestimate how extreme and homogeneous the other side is. Democrats think all Republicans are far-right conservatives; Republicans think all Democrats are radical leftists. The reality - that both parties contain a wide spectrum of views - gets lost in the cognitive flattening.

In media representation, the effect means that underrepresented groups are more likely to be portrayed through stereotypes while majority groups get nuanced, varied depictions. Nielsen's data on television representation reveals that streaming platforms are beginning to fill gaps for groups with historically low screen representation, but context matters as much as quantity. When outgroup members appear onscreen primarily as criminals, sidekicks, or comic relief, it reinforces rather than challenges the homogeneity effect.

Eyewitness misidentification across racial lines is a leading cause of wrongful imprisonment. When witnesses say "I'm certain," they may be unaware their brain processed the suspect through a categorical rather than individuated lens.

The obvious solution seems simple: more contact between groups should dissolve stereotypes by revealing individual differences. And to some extent, that's true. The contact hypothesis, one of social psychology's best-supported theories, holds that intergroup contact under optimal conditions - equal status, shared goals, cooperation, institutional support - reduces prejudice and increases perceived variability.

But contact alone isn't a magic bullet. You can interact with outgroup members daily and still see them as homogeneous if the conditions aren't right. The Wikipedia article on outgroup homogeneity notes that the bias persists even between men and women, who obviously have extensive contact. Why? Because mere exposure doesn't guarantee individuated processing. If your interactions remain superficial, if you're cognitively distracted, or if you're motivated to maintain group boundaries, contact won't help.

Studies show that the quality of contact matters more than quantity. Brief, positive, meaningful interactions that emphasize shared humanity are more effective than prolonged but shallow or antagonistic encounters. A single conversation where an outgroup member shares a personal story can do more to reduce bias than years of riding the same subway car.

This is where perspective-taking interventions come in - or rather, where they sometimes fall short. Research on political partisans found that only people who were already reflective could effectively take the perspective of opposing party members. Compassion training produced modest, often statistically insignificant improvements in feelings toward outgroups. The takeaway? Changing deeply ingrained biases requires more than a single intervention or a well-meaning workshop.

So if contact alone isn't enough and compassion training has limited effects, what works? The most effective strategies combine awareness, structural changes, and sustained practice.

Categorization flexibility training: Research shows you can reduce the outgroup homogeneity effect by learning to recategorize people along different dimensions. Instead of "us versus them," you create a superordinate category: "we." In one study, researchers reduced bias between rival university students by emphasizing their shared identity as "students" rather than their separate school affiliations. Similarly, in workplace settings, emphasizing shared professional goals or company identity can reduce departmental tribalism.

Counter-stereotypic exemplars: Deliberately seeking out examples that violate your group stereotypes helps break down categorical thinking. If you assume all conservatives oppose environmental protection, reading about Republican conservation efforts introduces cognitive dissonance that prompts more nuanced thinking. Media representation matters here: diverse storytelling that shows varied, complex outgroup members literally changes what your brain encodes.

"Representation by numbers is important - and so is the context when an identity group is seen on screen. Additionally, the themes in media content help shape perceptions and change beliefs."

- Nielsen Being Seen on Screen Report

Perspective-taking with structure: While generic "walk in their shoes" exercises have mixed results, structured perspective-taking can work. The key is combining imagination with information. Read first-person accounts, engage with art and literature from outgroup perspectives, and then reflect on how their circumstances shape their viewpoints. The combination of cognitive and emotional engagement seems to matter more than either alone.

Blind evaluation systems: Since the bias operates partly outside conscious awareness, structural interventions that remove categorical information can be surprisingly effective. Symphony orchestras that adopted blind auditions dramatically increased the number of women hired. Companies using blind resume reviews see more diverse candidate pools advance. These approaches don't try to change minds directly; they simply prevent biased perception from influencing decisions.

Cognitive load reduction: Because stress and cognitive depletion make categorical thinking worse, organizations can reduce bias by improving decision-making conditions. Schedule important evaluations when people are fresh, not at day's end. Break complex decisions into smaller steps. Use decision aids that prompt individuated consideration.

Sustained intergroup dialogue: Unlike brief contact, ongoing structured dialogue programs show promising results. These typically involve regular meetings over weeks or months where participants discuss difficult topics with trained facilitators. One analysis found that extended dialogue increased awareness of bias and changed behaviors over time, unlike one-off training sessions that produced only temporary shifts.

Perhaps the most unsettling discovery about the outgroup homogeneity effect is how easily it's triggered. In a series of famous experiments known as the minimal group paradigm, psychologist Henri Tajfel demonstrated that people show ingroup favoritism and outgroup stereotyping even when groups are assigned randomly, anonymously, and for no meaningful reason.

In one version, researchers told participants they preferred either Kandinsky or Klee paintings based on a bogus test. That's it - no history, no interaction, no shared traits, just a trivial aesthetic preference they didn't even really have. Yet participants immediately began allocating more resources to their supposed ingroup and viewing the outgroup as less varied. The bias emerged from nothing more than an arbitrary label.

The minimal group paradigm reveals how little it takes to trigger us-them thinking: even arbitrary labels like random aesthetic preferences are enough to activate ingroup favoritism and outgroup stereotyping.

The implications are both depressing and hopeful. Depressing because it reveals how little is required to activate us-them thinking. Any difference - shirt color, random assignment, seating arrangement - can serve as a catalyst for categorization and homogenization. But hopeful because it also means these categories aren't fixed. If arbitrary distinctions can create the effect, then reframing boundaries or creating new, more inclusive categories can reduce it.

The outgroup homogeneity effect won't disappear. It's too deeply embedded in how our brains process social information, too useful as a cognitive shortcut, too reinforced by the structure of modern society that keeps groups segregated. But we're not helpless. Understanding the bias is the first step toward mitigating its damage.

The work happens at multiple levels. Individually, you can cultivate habits of mind that resist categorical thinking: seeking out counter-stereotypic examples, questioning your assumptions about outgroup uniformity, deliberately engaging with diverse perspectives. Interpersonally, you can create conditions for genuine contact that emphasizes equal status and cooperation. Structurally, institutions can implement blind evaluation systems, diversify media representation, and design decision-making processes that reduce cognitive load and increase accountability.

What we're really talking about is training your brain to see what's already there. The diversity within any outgroup isn't imaginary - it's as real as the diversity within your own group. The person you mentally filed under a generic category has a inner life as rich and complex as yours, shaped by experiences you haven't lived and perspectives you haven't considered. They're not a data point in a monolithic "them." They're an individual who happens to belong to groups you don't.

The outgroup homogeneity effect reveals something uncomfortable about human cognition: our perceptions aren't neutral recordings of reality but constructions shaped by evolutionary pressures, cognitive constraints, and social contexts. Recognizing that opens up the possibility of reconstruction. We can't eliminate the bias entirely, but we can make it harder for our brains to take the lazy route. We can insist on seeing individuals, not categories. We can build systems that force us to look past the labels.

Because here's the thing about seeing "them" as all the same: it's not just unfair to them. It impoverishes your own understanding of the world. Every time you reduce a complex group to a stereotype, you miss opportunities to learn, to connect, to change your mind. You trap yourself in a smaller, simpler world than the one that actually exists.

The reality is messier, more contradictory, more interesting. They're not all the same. We're not all the same. And recognizing that - really internalizing it - might be the first step toward building institutions and communities where everyone gets seen as the complicated individual they actually are.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

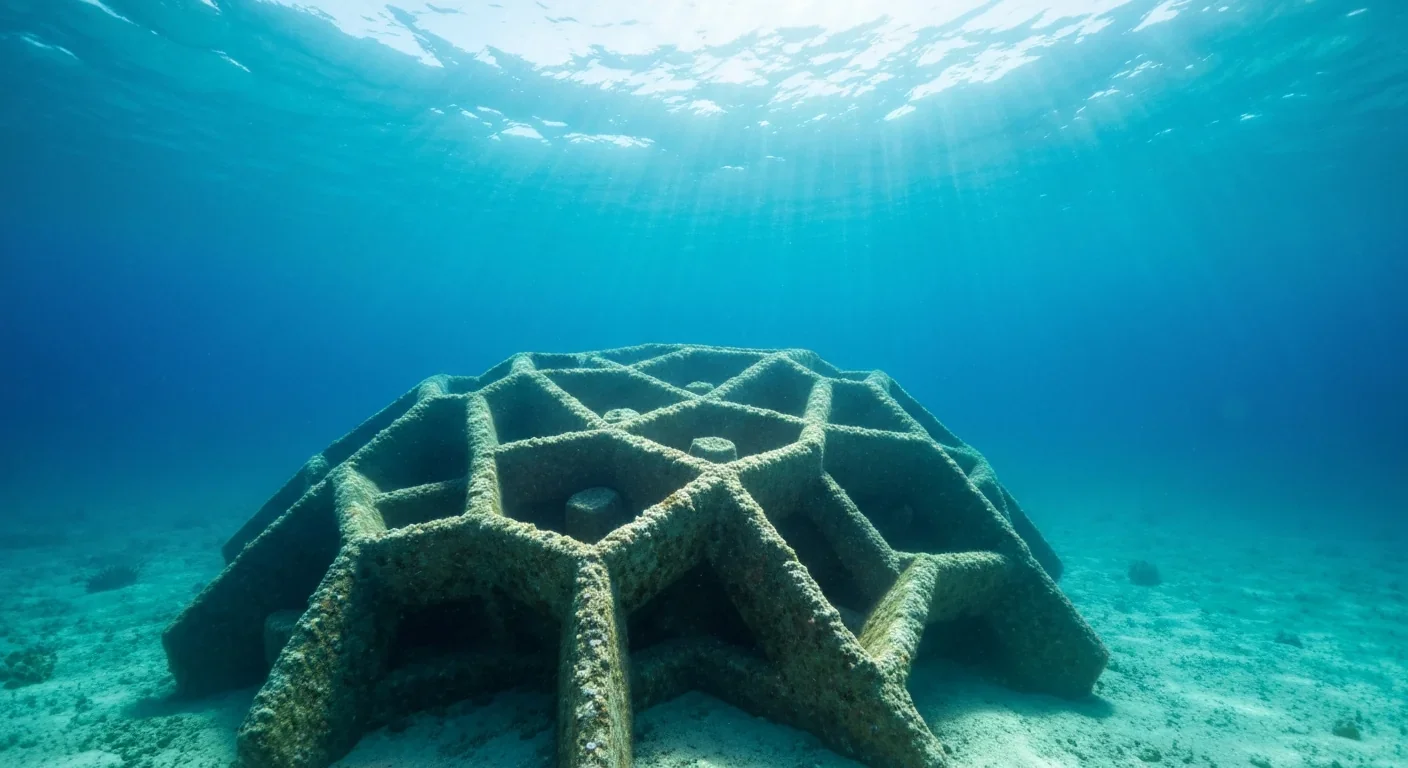

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

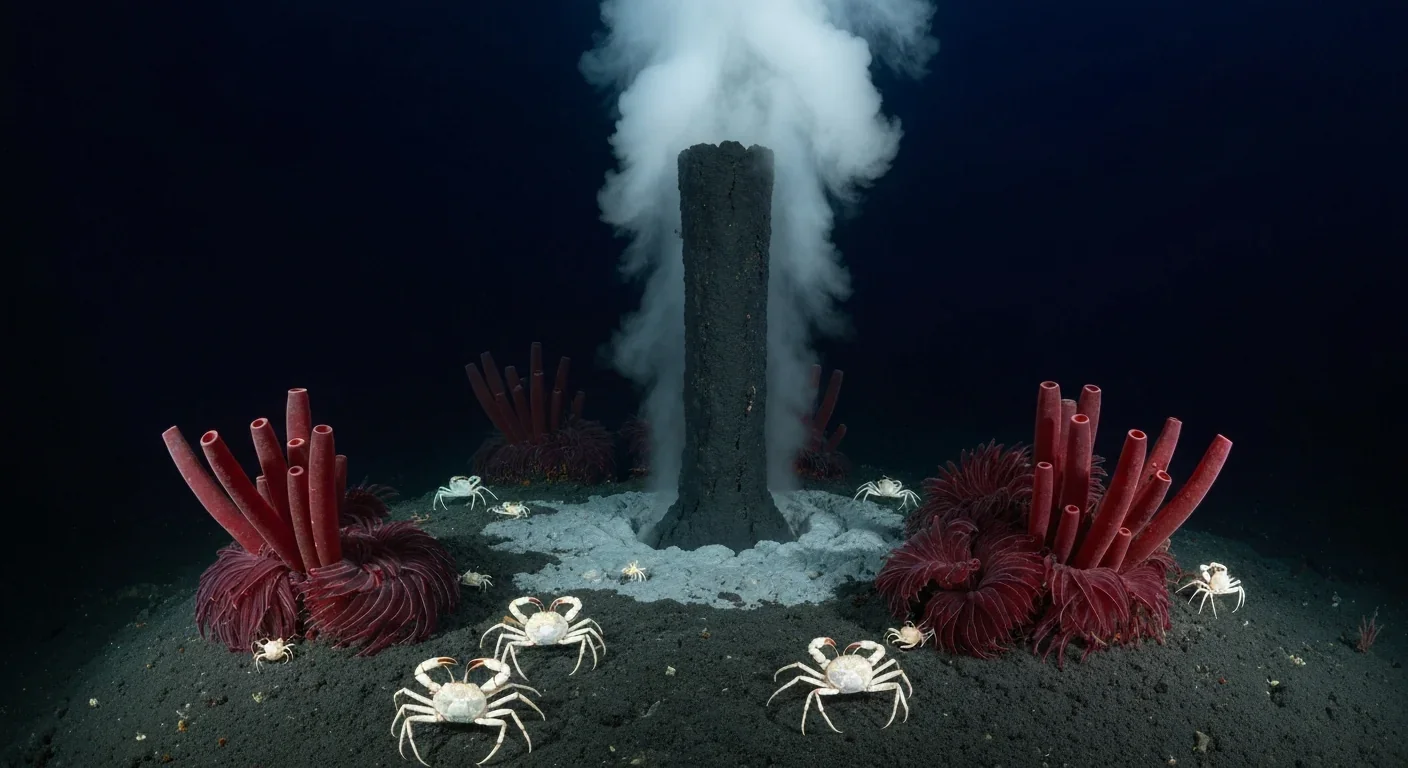

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

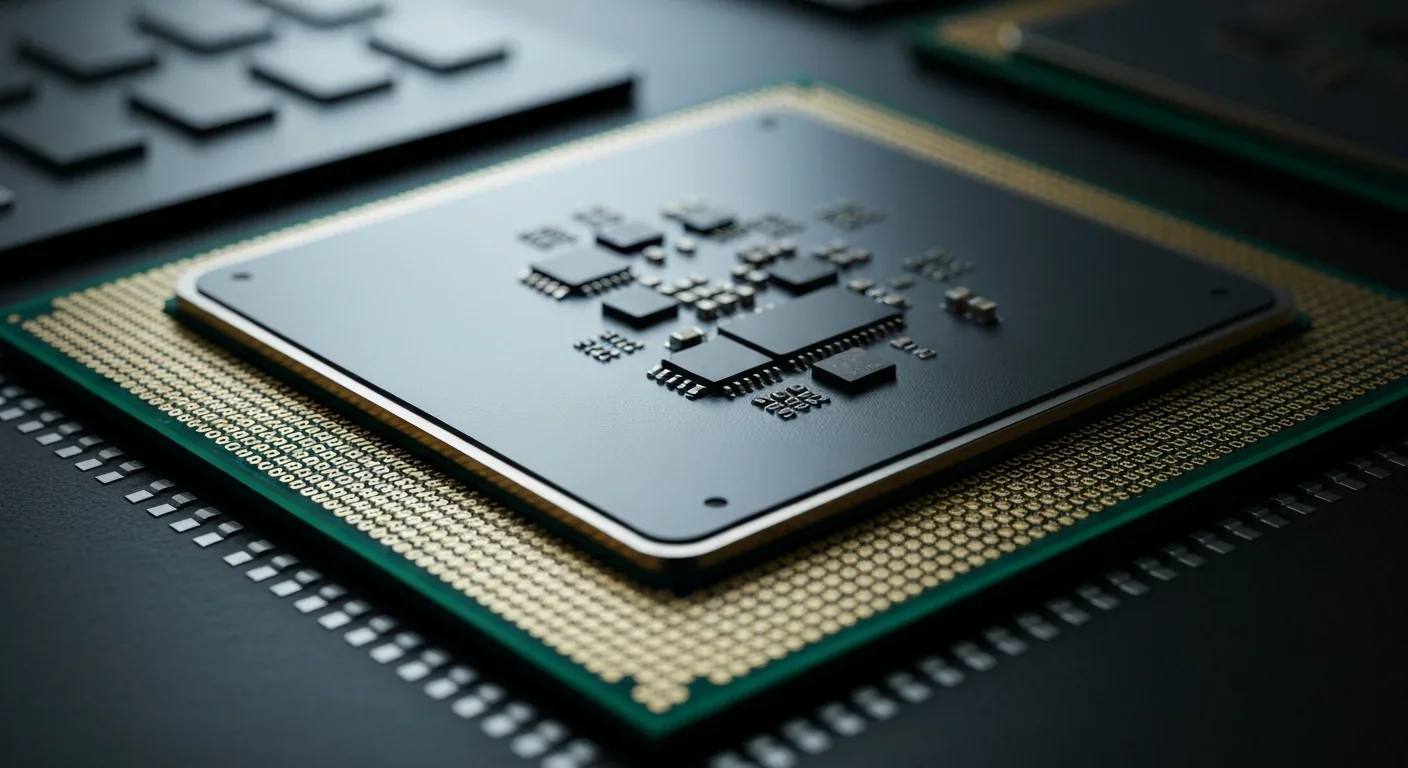

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.