The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The decoy effect is a cognitive bias where companies insert strategically inferior third options to manipulate your purchasing decisions. This psychological exploit works by hijacking your brain's tendency to make relative comparisons rather than absolute value judgments, boosting premium option sales by 30% or more.

You're standing at a coffee shop, scanning the menu. Small for $2.50, medium for $4.25, large for $4.50. The choice seems obvious - why would anyone pick the medium when the large costs barely more? That's exactly what they want you to think. And you just fell for one of the most powerful pricing tricks in behavioral economics.

Welcome to the decoy effect, a cognitive bias where businesses insert a third option - strategically designed to be terrible - just to make you spend more money. It's not about giving you choices. It's about controlling which choice you make.

The wildest part? You probably encounter this manipulation several times a day without realizing it. Movie theater popcorn, streaming subscriptions, smartphone storage plans, software packages - they're all using the same psychological exploit. And it works shockingly well, boosting sales of premium options by 30% or more in controlled experiments.

The decoy effect isn't about what you want. It's about how your brain evaluates options when it can't figure out what you want.

Here's the thing: humans are terrible at assessing absolute value. We can't look at a coffee and intuitively know if $4 is fair. What we can do - what we're hardwired to do - is compare. And when companies understand this, they can architect your decisions.

Research published in the Journal of Consumer Research shows that when faced with two similar options, people often feel uncertain. They split roughly 50-50 between them. But add a third option that's slightly worse than one of the originals, and suddenly that original becomes the overwhelming favorite. Not because it changed, but because you now have a reference point that makes it look like a bargain.

The mechanism is fascinating. Your brain doesn't evaluate each option independently. Instead, it creates a mental comparison map. The strategically inferior option acts as an anchor, a benchmark that skews your entire perception of value. You're not choosing the best option - you're choosing the option that looks best relative to the deliberately bad one.

Translation? The decoy effect bypasses your analytical thinking and triggers your brain's shortcut mode.

Neuroscientists studying this phenomenon with fMRI scanners discovered something remarkable: when people encounter a decoy, their anterior insula lights up. That's the brain region associated with processing salience and making quick, heuristic decisions. Meanwhile, the anterior cingulate cortex - responsible for cognitive control and conflict resolution - shows less activity in people who fall for decoys.

The most famous demonstration of the decoy effect came from MIT professor Dan Ariely, who noticed something strange about The Economist magazine's subscription pricing.

The options were baffling: web-only for $59, print-only for $125, and web plus print for $125. Who would choose print-only when the combo cost the same?

Ariely tested this on 100 MIT students. First, he showed them just two options: web-only ($59) and web-plus-print ($125). The students split 68% for web-only, 32% for the combo.

Then he added the print-only "decoy" at $125. The results flipped dramatically: now only 16% chose web-only, while 84% went for the combo. The print-only option? Just 1% chose it - because nobody was supposed to.

That useless middle option increased revenue from the target product by 30%. The Economist wasn't offering three options. They were offering two options and a psychological crowbar to pry open your wallet.

"The decoy is deliberately designed to be inferior to one of the other choices, making that option appear as more valuable."

- Behavioral Economics Research

The genius of this approach is that it feels like choice. You're not being told what to buy. You're being given options and making a rational decision. Except the deck is stacked, and your rationality is being weaponized against you.

The decoy effect is everywhere once you know to look for it. It's the architecture of modern consumer pricing.

Walk into any movie theater and check the popcorn prices. You'll typically see something like small for $4, medium for $6.50, and large for $7. That medium isn't there for people who want medium popcorn. It exists to make the large look like incredible value. You save $0.50 per serving compared to the medium? Sold.

Starbucks pioneered this in coffee sizing. Their three-size strategy isn't about accommodation - it's about making the venti feel like the smart choice. The grande is priced just close enough to make upgrading seem rational.

Look at smartphone storage plans. Apple doesn't offer 128GB, 256GB, and 512GB because they think you need those exact increments. They offer 128GB at a base price, 256GB at a moderate premium, and 512GB at barely more than the 256GB. Suddenly, that middle option makes 512GB look like the wise investment.

Software companies love this trick too. They'll offer a Starter plan at $19, a Pro plan at $49, and a Premium plan at $59. The Pro plan is the decoy - designed to be obviously inferior to Premium while making Premium look like it's basically free money for what you get.

Even streaming services use variants of this. They'll have a single-stream plan, a two-stream plan that costs almost as much as unlimited streams, and the unlimited plan that suddenly looks essential.

The pattern is always the same: create two genuine options, then insert a third option that exists solely to manipulate your perception of value.

What makes the decoy effect particularly insidious is how robust it is. Researchers have tried to break it, and it just keeps working.

Studies show the effect persists even when options are presented as scatter plots rather than written descriptions. Your brain falls for it whether you're reading words or looking at graphs.

It works across dramatically different domains too. The decoy effect has been documented in employee selection decisions, where hiring managers shift their preferences between candidates when a third, slightly inferior candidate is added to the pool. It influences apartment rentals, where landlords can steer tenants toward specific properties by including strategic alternatives.

The decoy effect isn't universal. It works best when you're nearly indifferent between two options - that's when the third option has maximum influence.

Even public health researchers have exploited it for good. When trying to increase colonoscopy screening rates, researchers offered patients three appointment options: a convenient hospital, a less convenient hospital, and a decoy hospital with terrible wait times. The decoy increased bookings at the convenient hospital by a significant margin.

The effect isn't universal, though. The original researchers noted that it works best when consumers are nearly indifferent between the target and competitor. If you already have a strong preference, a decoy won't budge you much. And some studies have found that the effect weakens when people have time to deliberate or when they're explicitly warned about manipulation tactics.

One fascinating neurological finding: people with higher activation in their anterior cingulate cortex - the brain's conflict-monitoring region - were more resistant to the decoy effect. This suggests that cognitive control and deliberate thinking can override the bias, at least for some people.

But here's the kicker: reaction times increase when a decoy is present. People take longer to decide, suggesting they're actually doing more mental work. They're not taking shortcuts - they're processing the comparison and concluding that the target option genuinely looks better. The decoy doesn't make decisions easier; it makes the manipulated choice feel more justified.

So how do you fight back against something that operates below conscious awareness?

The first step is recognition. The decoy effect exploits relative comparisons rather than absolute value assessments. Once you spot the pattern - three options with one that's weirdly worse - you can catch yourself.

Try this mental exercise: cover up the middle option and re-evaluate. If you were choosing between just the cheapest and most expensive options, which would you pick? If adding the middle option back in changes your mind, you're being played.

Calculate value per unit rather than looking at total price. For popcorn, work out the price per ounce. For software subscriptions, divide the monthly cost by features. For phones, look at storage cost per gigabyte. Absolute metrics cut through relative manipulation.

Better yet, know what you want before you see the options. If you walk into a coffee shop knowing you want a small coffee, the decoy can't work because you're not in comparison mode. The bias is strongest when you're uncertain.

"Studies consistently show that education about cognitive biases reduces their impact. Awareness is a powerful antidote."

- Consumer Psychology Research

Studies show awareness significantly reduces susceptibility. People who've learned about the decoy effect are less likely to fall for it in subsequent encounters. That's why businesses don't advertise that they're using it.

And when you spot egregious examples, call them out. Take a photo of the pricing, post it online, tag the company. Public pressure can work. Consumers who feel manipulated tend to become former customers.

This raises uncomfortable questions about the line between smart marketing and manipulation.

On one hand, businesses argue they're simply presenting options and letting consumers choose. Nobody's forcing you to buy the large popcorn. You made that decision freely based on available information.

On the other hand, there's something deeply troubling about architecting choices to exploit known cognitive biases. The decoy effect violates the independence of irrelevant alternatives - a fundamental axiom of rational choice theory. In a purely rational world, adding a third option that you don't choose shouldn't change your preference between the first two options. But it does, because we're not rational - we're predictably irrational.

Consumer advocates argue that decoy pricing constitutes a form of deceptive practice. You think you're evaluating options fairly, but the game is rigged. The menu isn't information - it's a psychological weapon.

Some researchers have called for transparency requirements. If companies are using decoys, should they be required to disclose it? Would that even help, or would it just normalize the practice?

There's also the question of where this stops. If decoy pricing is acceptable, what about other forms of behavioral manipulation? AI and machine learning are making it possible to create personalized decoys based on your browsing history and purchase patterns. Imagine a future where every price you see is optimized to exploit your specific cognitive weaknesses.

There's a difference between persuasion and exploitation. Persuasion respects agency; exploitation bypasses it.

The counterargument is that capitalism has always involved persuasion, and decoy pricing is just a more sophisticated version of "sale" tags and "limited time offers." We don't ban advertising just because it's designed to influence behavior.

But there's a difference between persuasion and exploitation. Persuasion respects agency; it tries to convince you that something is valuable. Exploitation bypasses agency; it manipulates the cognitive machinery that underlies choice.

The decoy effect isn't going anywhere. If anything, it's becoming more sophisticated.

E-commerce platforms are using AI to test thousands of pricing variations, optimizing decoys in real-time based on conversion data. Machine learning algorithms can identify the perfect price point for a decoy that maximizes revenue without being so obvious that it triggers consumer skepticism.

Digital interfaces make testing easier too. A/B testing lets companies run experiments on millions of users simultaneously, identifying which decoy structures work best for different demographics, times of day, or product categories.

Some companies are getting creative with the format. Instead of three pricing tiers, they'll offer two main options and then show customer testimonials highlighting how many people chose the premium option. The social proof becomes the decoy - you're not comparing features, you're comparing yourself to other buyers.

There's also a fascinating trend in "reverse decoys." Some brands will intentionally offer a very cheap option that's so obviously inferior that it makes even the mid-tier option look premium. The decoy isn't pushing you toward the most expensive choice - it's establishing a floor that reframes everything else as higher-quality.

The rise of subscription models has supercharged decoy pricing. When you're committing to monthly payments, the psychological calculus changes. A $10 difference per month feels trivial - that's just three coffees - but it compounds to $120 per year. Decoys in subscription pricing are especially effective because people underweight future costs.

What's emerging is a science of choice architecture that goes far beyond simple pricing. Companies are designing entire customer journeys to funnel people toward specific decisions, with decoys embedded at multiple stages.

The decoy effect reveals something profound about how we make decisions. We like to think we're rational actors, carefully weighing options and choosing what's best. But we're actually pattern-matching machines, constantly looking for comparisons and shortcuts.

That's not a bug in human psychology - it's a feature. In most situations throughout human evolution, relative comparisons were incredibly useful. If one berry bush has more fruit than another, go to the first bush. You don't need absolute metrics; you need relative ones.

The problem is that modern marketers have figured out how to hijack this adaptive mechanism. They're not just competing to offer the best product at the best price. They're competing to design the choice environment that manipulates your perception most effectively.

But awareness is a powerful antidote. The more people understand the decoy effect, the more resistant they become to it. Studies consistently show that education about cognitive biases reduces their impact.

So next time you're faced with three options and one seems weirdly worse, pause. Ask yourself if the middle option is a genuine choice or a psychological crowbar. Cover it up mentally and re-evaluate.

Because here's the thing: when you spot the decoy, it stops working. The illusion breaks. And suddenly, you're making a choice based on what you actually want, not what someone engineered you to want.

That's the difference between being a consumer and being a mark. And in a world where every company has a behavioral economics team optimizing your decisions, knowing the difference matters more than ever.

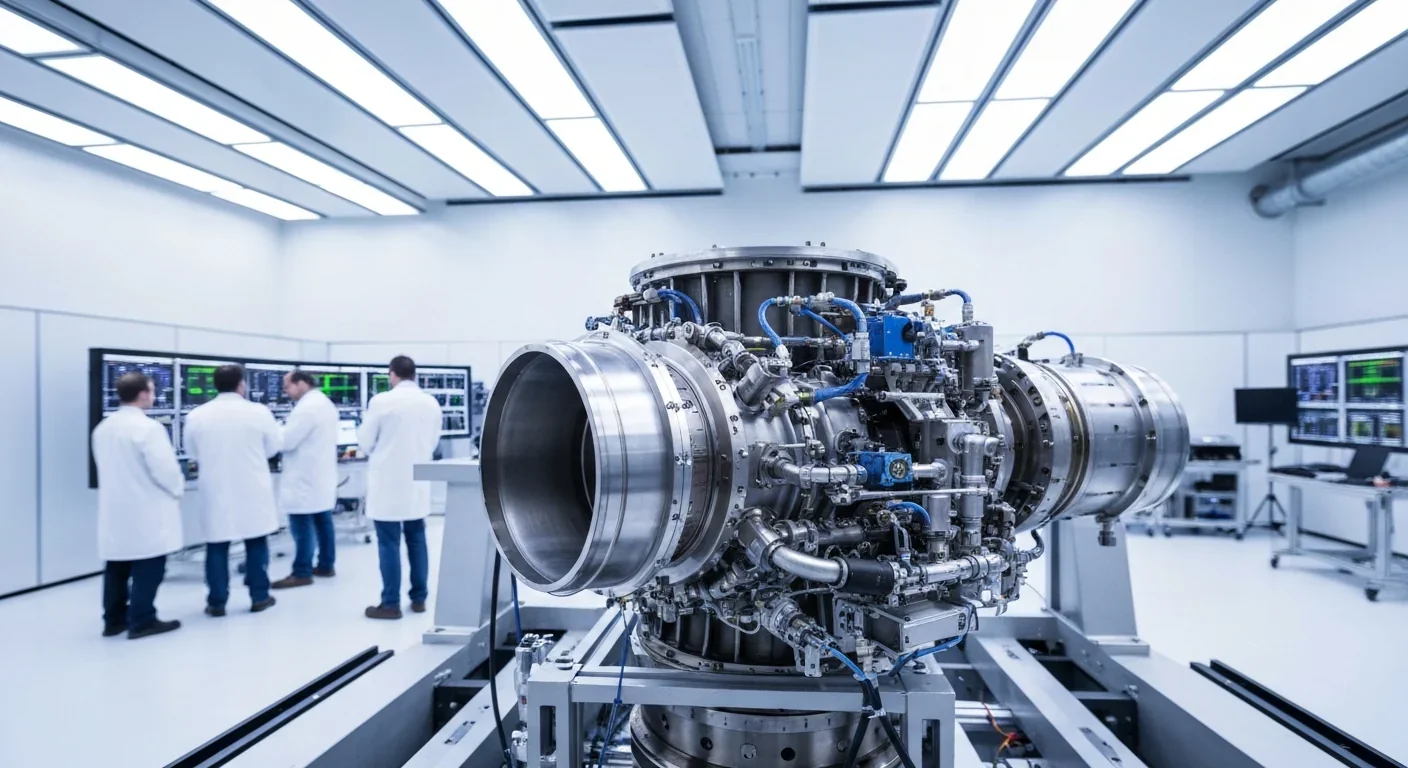

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

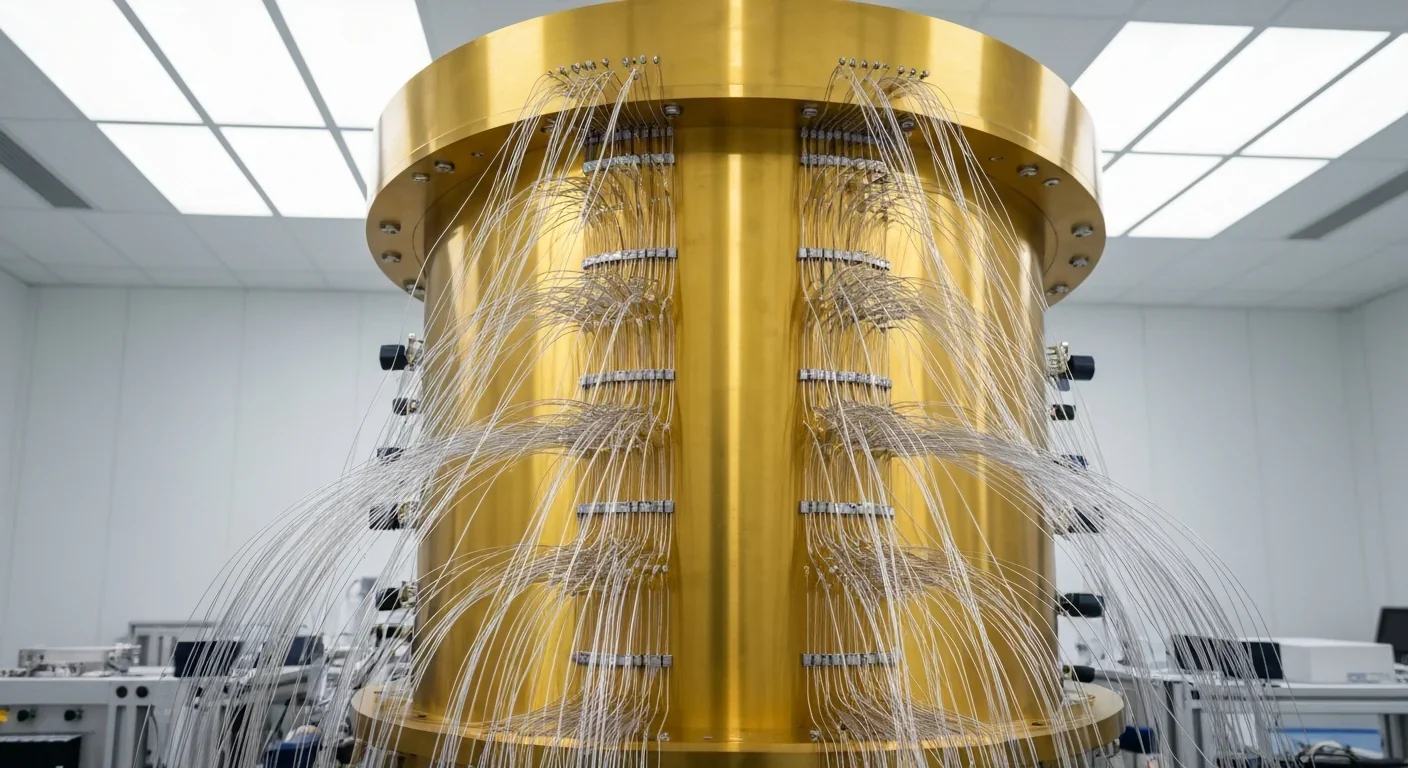

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.