The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: How information is presented shapes our decisions more than the actual content. The framing effect exploits cognitive biases, making negative frames feel more powerful than positive ones, even when describing identical outcomes.

A doctor tells you a surgery has a 90% survival rate. You feel reassured. Another doctor describes the same procedure with a 10% mortality rate. Suddenly, it feels riskier. Nothing changed except the words, yet your entire decision calculus just shifted. Welcome to the framing effect, the cognitive bias that proves we're far less rational than we'd like to believe.

This isn't about spin or propaganda, though those certainly exploit it. The framing effect operates at a deeper level, fundamentally altering how we process identical information based solely on presentation format. It's the reason "95% fat-free" sells better than "5% fat," why politicians talk about "job creators" instead of "the wealthy," and why you're more likely to try a medical treatment framed as preventing death rather than ensuring survival.

The implications reach far beyond marketing tricks. This bias shapes medical decisions, political choices, financial investments, and daily judgments in ways most of us never consciously recognize. But here's the thing: once you understand how framing works, you start seeing it everywhere. And that awareness becomes your first line of defense.

In 1981, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky published what would become one of the most influential experiments in behavioral economics. They presented people with a hypothetical scenario: an unusual Asian disease outbreak threatens 600 lives. You must choose between two programs to combat it.

Group A saw these options:

- Program A saves 200 people (certain outcome)

- Program B has a 33% chance of saving all 600, but a 67% chance of saving no one

Most people chose the certain outcome of Program A. Who wants to gamble with lives?

Group B received mathematically identical options, just worded differently:

- Program C means 400 people will die (certain outcome)

- Program D offers a 33% chance that nobody dies, but a 67% chance all 600 die

This time, most people chose the gamble. The thought of 400 certain deaths felt unbearable.

The math is identical in both scenarios, yet framing through gains versus losses completely reversed people's preferences. We don't evaluate information objectively - we evaluate it relative to how it's framed.

Here's what makes this profound: both scenarios describe the exact same outcomes. Saving 200 people means 400 die. A 33% chance of saving everyone means a 67% chance of saving no one. The math is identical, yet framing through gains versus losses completely reversed people's preferences.

This wasn't irrational people making bad choices. These were intelligent individuals whose decisions were systematically altered by presentation format. The experiment revealed something unsettling: we don't evaluate information objectively. We evaluate it relative to how it's framed, and that frame often matters more than the content itself.

The framing effect isn't a bug in human cognition. It's a feature that evolved for good reasons but creates problems in modern information environments.

Our brains operate on two systems, as Kahneman later explained in his prospect theory work. System 1 thinks fast, relying on intuition, emotion, and mental shortcuts. System 2 thinks slow, engaging in deliberate analysis and logical reasoning. Framing exploits System 1's dominance in most decisions.

When you hear "90% survival rate," your System 1 brain quickly categorizes this as positive, triggering approach motivation. The emotional tone feels optimistic. Your mind moves forward without much deliberation. But "10% mortality rate" activates threat detection mechanisms, triggering avoidance motivation and caution. Same information, completely different emotional activation.

This happens because of loss aversion, another discovery from Kahneman and Tversky's research. Losses loom approximately twice as large as equivalent gains in our mental accounting. Losing $100 hurts more than gaining $100 feels good. This asymmetry makes negative frames more psychologically powerful than positive ones.

The mechanism works through reference points. Our judgments aren't absolute - they're relative to whatever anchor or reference the frame establishes. Tell someone a product costs $500, down from $800, and they evaluate it against the $800 reference point, making $500 seem reasonable. Present the same $500 price without context, and it might feel expensive. The frame sets the mental measuring stick.

Context and associations matter too. The framing of information activates related concepts in memory through associative networks. Describing a ground beef as "75% lean" primes thoughts about health and quality. Calling it "25% fat" activates concerns about cholesterol and weight gain. The actual beef hasn't changed, but the mental associations have.

Politicians didn't invent framing, but they've turned it into a science. George Lakoff, a cognitive linguist who has advised Democratic strategists, argues that political frames aren't just about messaging - they activate entire worldviews.

Consider "tax relief." The word "relief" implies taxes are an affliction, something oppressive that good leaders remove. The frame isn't neutral; it embeds a political philosophy. Alternative frames like "tax responsibility" or "membership fees for civilization" would activate completely different associations, but they're harder to establish once a frame dominates public discourse.

Frank Luntz, a Republican strategist, famously reframed "estate tax" as "death tax" in the 1990s. The estate tax applied to roughly 2% of Americans, but calling it a death tax made it feel like government profiting from grief, affecting everyone. Support for repealing the tax increased dramatically after the reframing campaign, even among people who would never pay it.

The power extends beyond individual phrases. Entire policy debates get shaped by frame dominance. Immigration discussions framed around "border security" versus "family separation" lead to different conclusions despite discussing the same policies. Climate change framed as "environmental protection" activates different mental models than "economic transformation" or "energy freedom."

"Political frames aren't just about messaging - they activate entire worldviews that determine how we interpret new information and make judgments."

- George Lakoff, Cognitive Linguist

What makes political framing so effective is its interaction with motivated reasoning - our tendency to accept information confirming existing beliefs while scrutinizing contradictory information. A well-chosen frame doesn't need to convince everyone. It just needs to resonate with its target audience's existing worldview, reinforcing what they already want to believe.

Recent research on narrative framing in political discourse shows that stories prove more persuasive than statistics because narratives provide ready-made frames. A single compelling story about someone affected by a policy creates a stronger frame than aggregate data on thousands of people. Our brains didn't evolve to process statistics. They evolved to understand stories, making narrative frames particularly potent.

Walk into any store and you're navigating a carefully constructed framing environment. That's not accident or aesthetics - it's applied behavioral economics.

The "was $99, now $59" tag exploits anchoring effects through price framing. The $99 anchor makes $59 seem like a bargain, even if the product was never actually sold at the higher price. Research shows consumers spend more when presented with higher reference prices, regardless of whether those prices are legitimate or arbitrary.

Product descriptions reveal framing in action. "80% lean ground beef" outsells "20% fat ground beef" despite describing identical products. "All-natural ingredients" frames a product through positive associations with nature and purity, while an equivalent description like "no artificial ingredients" emphasizes what's absent, creating a weaker appeal.

Limited-time offers create temporal framing that triggers loss aversion. "Sale ends Sunday" makes not buying feel like losing an opportunity. The scarcity frame transforms a neutral decision (whether to purchase) into an urgent one (whether to miss out).

Free shipping thresholds provide another elegant framing application. "Free shipping on orders over $50" reframes the decision from "should I buy this $35 item" to "should I add $15 more to get free shipping." The frame shifts your reference point from evaluating a single purchase to optimizing for a shipping benefit, often leading to higher total spending.

The marketing applications extend to digital interfaces too. Subscription services frame pricing as "just $10 per month" rather than "$120 per year" because smaller units feel less painful. The opposite applies when companies want to emphasize value: "Save $120 annually" sounds better than "Save $10 monthly."

Color and imagery create visual frames that activate different emotional states. Red often frames urgency and excitement, useful for clearance sales. Blue frames trust and reliability, common in financial services. These aren't universal - cultural context matters enormously - but within specific markets, visual framing follows predictable patterns.

Healthcare represents the highest-stakes framing arena because decisions involve life and death, but most patients lack expertise to evaluate medical information objectively.

When doctors present treatment options, how they frame statistics dramatically affects patient choices. Research shows patients are more likely to choose surgery when told it has a 90% survival rate than when told it has a 10% mortality rate, even though these describe identical outcomes. The positive frame emphasizes what you keep (life), while the negative frame emphasizes what you lose (death).

This creates genuine ethical dilemmas. Should doctors deliberately frame information to encourage what they believe is the best choice? That could improve health outcomes but undermines informed consent. Presenting "neutral" information proves nearly impossible since any presentation involves framing choices about what to emphasize, what order to present information, and what reference points to establish.

Critical Healthcare Question: When the same medical information framed differently leads to opposite decisions, how can we ensure true informed consent? The challenge isn't just communication - it's that objective presentation may be impossible.

Medication adherence studies reveal how framing influences patient behavior after leaving the doctor's office. Telling patients that taking medication reduces their heart attack risk by 30% proves more effective at encouraging adherence than saying 70% will still be at risk. Both statements are mathematically equivalent, but the gain frame motivates action while the loss frame can induce helplessness.

Screening recommendations face similar challenges. When discussing mammograms or colonoscopies, emphasizing the chance of early detection (gain frame) increases uptake compared to emphasizing risks of missing a diagnosis (loss frame), even though both describe the same screening benefit.

The rise of patient-centered care has amplified these challenges. Shared decision-making sounds ideal - patients should participate in their own care decisions. But truly shared decisions require patients to understand information objectively, which framing makes nearly impossible. A 2015 study using skin conductance responses showed that different frames create measurable physiological stress responses, demonstrating that framing doesn't just change thoughts but emotional states.

Your investment decisions are shaped by frames you probably don't notice. Financial services companies employ behavioral economists specifically to design framing strategies that influence client choices.

The most common application involves defaults. When companies frame retirement savings plans with automatic enrollment (you must opt out to not participate) versus opt-in enrollment (you must actively choose to participate), participation rates differ dramatically. The framing doesn't change the program's economics, but automatic enrollment boosts participation by 30-40 percentage points. The default option becomes the reference point, and deviating from it feels like taking action rather than maintaining status quo.

Investment performance gets framed through carefully chosen time periods and benchmarks. A fund that lost money over one year might show gains over five years. Neither timeframe is wrong, but each tells a different story. Financial institutions typically choose the frame that makes their products look best, which is legal as long as the underlying numbers are accurate.

Risk tolerance questionnaires reveal framing's power in financial planning. Ask someone whether they prefer an investment with "a high potential for growth but significant short-term volatility" versus one with "uncertain returns that could lose value frequently," and you'll get different responses despite describing similar risk profiles. The first frame emphasizes opportunity; the second emphasizes threat.

Mortgage framing plays with temporal perception. "$2,000 per month" feels different than "$240,000 over ten years," even though they're mathematically identical. The monthly frame makes the commitment feel manageable, while the total amount reveals the true cost. Both frames are accurate, but lenders tend to emphasize monthly payments.

The framing of financial decisions around retirement reveals particularly interesting patterns. "You'll need $2 million to retire" creates anxiety and can paralyze action. "Saving $500 per month starting at age 30" frames the same goal as an achievable action. The first frame establishes an intimidating end state; the second frames a manageable process.

Framing isn't universal. What works in one culture can completely misfire in another because cultural context provides the interpretive framework through which frames operate.

Research on cultural differences in framing effects shows that individualistic Western cultures respond more strongly to frames emphasizing personal benefits and autonomy, while collectivist Eastern cultures respond better to frames emphasizing group harmony and social responsibility. The same information framed through different cultural values activates different decision-making pathways.

Political frames that work in the United States often fail in other democracies because they rely on specifically American associations. "Freedom" carries enormous positive weight in U.S. political discourse, making "health care freedom" or "school choice freedom" powerful frames. In countries with stronger social democratic traditions, "solidarity" or "collective responsibility" might carry more persuasive weight.

News coverage demonstrates cultural framing differences clearly. Events covered by media in different countries receive not just different emphasis but entirely different interpretive frames. An economic policy might be framed as "promoting growth" in business-friendly publications or "increasing inequality" in left-leaning outlets. Both frames can be supported with facts, but they activate different evaluative criteria.

Language structure itself influences framing susceptibility. Grammatical requirements that differ across languages may affect how effectively certain framing strategies work, making frame effectiveness culturally contingent.

Media literacy education programs increasingly recognize that identifying bias isn't enough - you need to identify framing strategies. A recent European study found that teaching students to recognize media framing techniques improved their ability to extract substance from presentation, though the effects were modest and required sustained practice.

Knowing about the framing effect doesn't make you immune, but it does provide tools for more objective decision-making.

The first strategy involves active reframing. When you encounter information, deliberately reformulate it using opposite or neutral frames. If you're told a treatment has a 90% success rate, translate that to a 10% failure rate. If an investment emphasizes potential gains, consider potential losses. This mental exercise doesn't tell you which frame is "correct" - both describe reality - but comparing frames helps you see the substance underneath the presentation.

Research on debiasing techniques suggests that considering alternative perspectives systematically reduces framing effects. A 2015 study found that people who listed three reasons to reject their initial framed judgment made decisions closer to those who received neutral information. The intervention isn't complicated, but it requires conscious effort to override System 1's quick judgment.

Creating distance helps too. Imagining you're advising a friend rather than making a decision for yourself can reduce emotional engagement with specific frames. This psychological distancing allows more analytical processing. Ask yourself: would I recommend this choice to someone I care about based on how it's described, or based on what the description actually means?

Decision-making frameworks that force systematic comparison reduce framing susceptibility. Making a list of pros and cons, assigning weights to different criteria, and scoring options against those criteria requires engaging System 2 thinking. This structured approach doesn't eliminate framing effects entirely, but it reduces their impact.

Time delays serve as another useful tool. Immediate responses increase framing susceptibility because they rely more heavily on System 1 processing. Waiting 24 hours before finalizing important decisions gives System 2 time to engage. This is why "cooling-off periods" exist in consumer protection law - they create space for analytical thinking to catch up with emotional reactions.

"The goal isn't to become emotionless. It's to recognize high-stakes situations where presentation might override substance, and in those moments, deliberately engage more careful analysis."

- Behavioral Economics Research

Question the messenger's incentives. Who benefits if you accept their frame? This doesn't mean everyone using frames is manipulating you - sometimes frames genuinely help communicate complex information - but incentive awareness helps you evaluate whether a frame illuminates or obscures substance.

Seek multiple sources framing the same information differently. If you only encounter one frame, it becomes invisible. Exposure to competing frames makes the framing itself visible, allowing you to evaluate substance more independently. This is why media diversity matters for democratic decision-making.

Practice recognizing common framing techniques: anchor pricing, temporal framing (now versus later), gain versus loss framing, absolute versus relative numbers, and reference point manipulation. Like learning to spot card tricks, understanding the technique helps you see through the performance.

As artificial intelligence increasingly mediates information flow, framing becomes both more powerful and potentially more insidious.

AI systems trained on human language naturally learn framing strategies embedded in their training data. When large language models generate text, they reproduce culturally dominant frames unless explicitly prompted to provide alternatives. This means AI could amplify existing framing patterns, making dominant frames even more dominant.

Personalized framing represents the next frontier. Imagine AI systems that analyze your psychological profile and automatically present information using frames most likely to persuade you specifically. Microsoft Research's work on media bias detection tools shows that automated framing analysis is feasible, but the same technology could enable automated framing optimization.

This creates potential for unprecedented manipulation. A pharmaceutical company could use AI to present drug information using frames most effective for each patient's psychological profile. Political campaigns could deliver messages with personalized framing based on your social media data. The technology to do this already exists or is emerging rapidly.

But AI also offers defensive possibilities. Bias detection tools could automatically reframe information you encounter, presenting multiple frames to reveal the substance underneath. Browser extensions or reading applications could flag framing techniques as you encounter them, providing real-time cognitive support for more objective evaluation.

The ethical implications become profound in high-stakes domains. Should AI systems be allowed to optimize medical treatment explanations for persuasiveness? That might improve health outcomes but could undermine informed consent. Should political campaigns be permitted to use AI for micro-targeted framing? That might increase engagement but could fragment shared reality further.

Regulation faces significant challenges. Framing isn't false information, so truth-in-advertising laws provide limited protection. Yet framing can mislead as effectively as lies by highlighting facts that support desired conclusions while downplaying contradictory evidence. Traditional legal frameworks weren't designed for cognitive biases operating below conscious awareness.

The framing effect reveals something uncomfortable: we're not the rational decision-makers we imagine ourselves to be. Our judgments are systematically influenced by factors we don't consciously notice and wouldn't endorse if we did.

But this knowledge itself provides power. Understanding that your initial reaction to information likely reflects its framing more than its substance creates space for deliberation. You can't eliminate framing effects - they're too deeply embedded in cognition - but you can learn to recognize when you're being framed and engage analytical thinking to examine what lies beneath the presentation.

The goal isn't to become emotionless or eliminate all heuristic thinking. System 1 processing serves important functions, allowing quick decisions when needed. The goal is to recognize high-stakes situations where presentation might override substance, and in those moments, deliberately engage more careful analysis.

This matters increasingly in an information environment designed to capture attention and drive behavior. Every interface, message, and choice architecture embeds framing decisions made by someone with objectives that may not align with your interests. Developing framing literacy won't give you perfect objectivity, but it can help you see the manipulation and make choices based more on substance than on how that substance was packaged.

The frames are everywhere. Now you can start seeing them.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

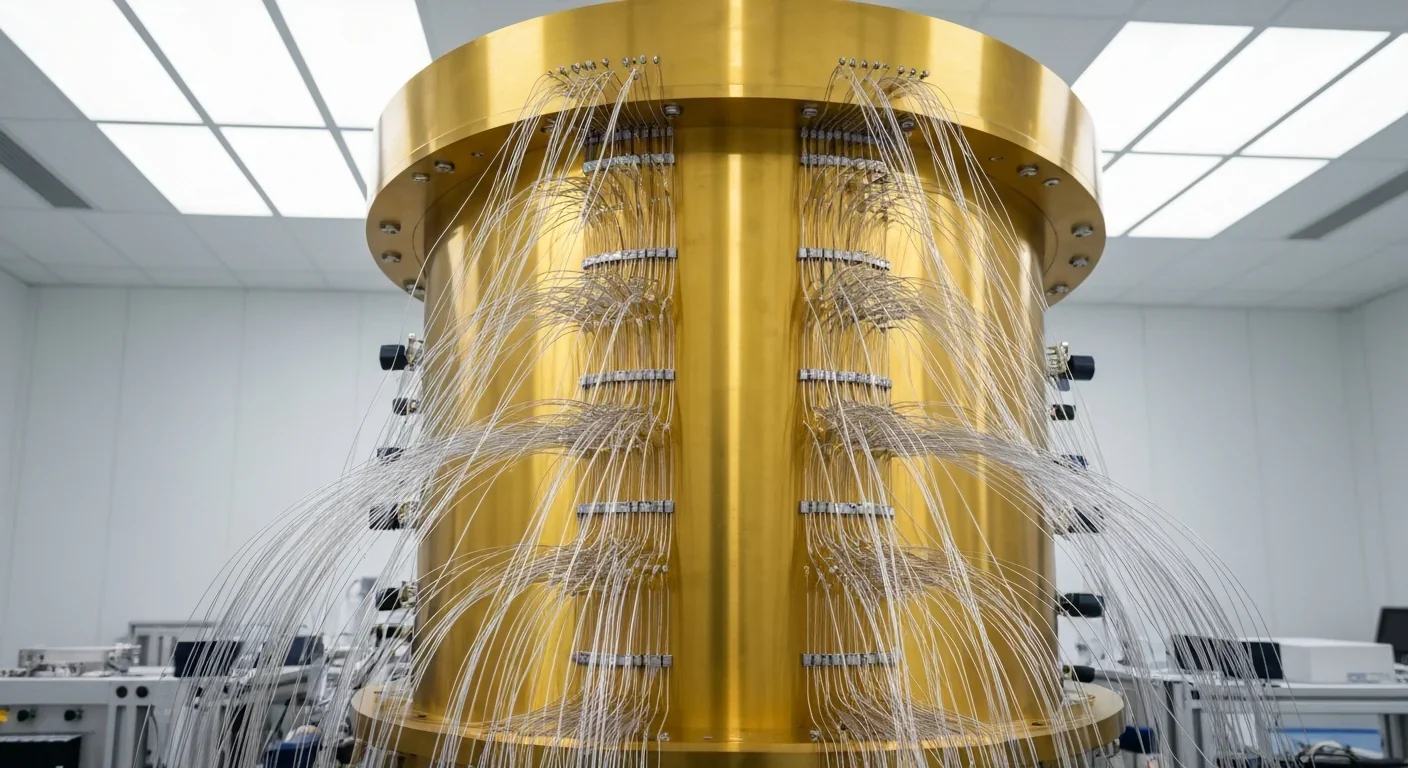

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.