The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Hindsight bias makes past events seem predictable after they occur, warping how we learn, judge others, and make decisions. This article explores the neuroscience behind this cognitive illusion and provides actionable strategies to overcome it.

We've all done it. After an election result, you insist you saw it coming. When a friend's relationship falls apart, you think back and claim the warning signs were obvious. Your colleague's failed startup? You remember thinking it was doomed from the start. But here's the uncomfortable truth: you probably didn't know. Your brain is rewriting history, and this mental sleight of hand is costing you more than you realize.

This isn't just about being annoying at parties. Hindsight bias, the psychological phenomenon where past events seem more predictable after they occur, fundamentally warps how you learn from experience, evaluate others, and make future decisions. It creates a false sense of expertise that can lead investors to financial ruin, doctors to misdiagnose patients, and juries to convict the innocent.

Think of your memory like a Wikipedia page that anyone can edit, except the only editor is your current self with full knowledge of how things turned out. Every time you recall an event, your brain doesn't replay a video recording. Instead, it reconstructs the memory from fragments, and those fragments get contaminated by what you know now.

Research shows that each time you recall something, your brain slightly alters the memory based on new experiences and perspectives. Once you know an outcome, it becomes nearly impossible to remember what it felt like not to know. The uncertainty you felt beforehand gets erased, replaced by a tidy narrative where everything made sense all along.

Once you know an outcome, it becomes nearly impossible to remember what it felt like not to know. Your brain automatically erases the uncertainty you felt beforehand and replaces it with a tidy narrative where everything made sense all along.

Psychologist Baruch Fischhoff, who pioneered research on hindsight bias in the 1970s, discovered something fascinating: when people are told an outcome, they not only believe they would have predicted it, they actually misremember their original predictions to align with what happened. Your brain isn't just fooling you in the moment. It's rewriting your personal history.

The mechanism behind this involves what researchers call "narrative coherence." Your brain craves stories that make sense. A disordered past feels unsettling, so your mind automatically reconstructs events into clean cause-and-effect chains. The problem? Real life is messier than our retrospective stories suggest.

The consequences play out across every domain of human decision-making, often with devastating results.

Cognitive biases in clinical decision-making create serious diagnostic errors. A patient presents with vague symptoms: fatigue, occasional chest pain, mild nausea. The doctor orders routine tests, finds nothing alarming, and sends the patient home. Three days later, the patient has a heart attack.

In hindsight, the signs seem glaringly obvious. The family insists the doctor should have known. Medical review boards, looking backward with full knowledge of the outcome, judge the physician's decision as negligent. But at the time of the examination, those same symptoms could have indicated dozens of conditions, most of them minor.

This "visual hindsight bias" particularly affects radiologists, who face lawsuits when they miss findings on scans that seem obvious once another radiologist, knowing what to look for, reviews the same images. The second radiologist has an unfair advantage: they know the diagnosis and exactly where to focus their attention.

Dr. Laura Zwaan's research on learning from medical mistakes reveals that hindsight bias prevents healthcare professionals from extracting useful lessons from errors. When doctors convince themselves they "should have known," they focus on the wrong learning points and fail to improve their actual diagnostic processes.

Walk into any bar after a stock market crash and you'll hear a chorus of investors claiming they saw it coming. Hindsight bias in investing creates a dangerous cocktail of overconfidence and poor learning.

The dot-com bubble and the 2008 financial crisis are textbook examples. After the crashes, everyone claimed the warning signs were obvious. But if that were true, why did so many smart investors lose everything? The truth is that before the crash, the signals were mixed and ambiguous. Plenty of credible analysts argued both sides.

"When investors convince themselves they 'knew' which stocks would perform well, they become more willing to take on excessive risk, overtrade, and ignore contradictory signals."

- Investment Psychology Research

Investment research shows this bias operates in three distinct stages: memory distortion (misremembering your original prediction), inevitability (believing the outcome was bound to happen), and foreseeability (claiming you could have predicted it). Each stage reinforces the others, creating an illusion of expertise.

The most successful investors, including Warren Buffett and Ray Dalio, actively guard against this bias. Buffett focuses on intrinsic value rather than trying to predict market movements. Dalio uses systemized, rules-based diversification that removes emotional hindsight contamination from the process.

When investors convince themselves they "knew" which stocks would perform well, they become more willing to take on excessive risk, overtrade, and ignore contradictory signals. The result? Costly mistakes disguised as learning experiences.

Perhaps nowhere is hindsight bias more dangerous than in legal proceedings. Jurors hear about an accident and must decide whether the defendant should have foreseen the outcome and acted differently. But the jurors already know the outcome, and that knowledge makes the risk seem much more obvious than it would have been in the moment.

Research on juror biases reveals that hindsight bias leads to harsher judgments in negligence cases. When people know that a child was injured on a playground, they rate the playground equipment as far more dangerous than control groups who evaluate the same equipment without knowing about the injury.

This creates serious medicolegal implications. Doctors get sued for "missing" diagnoses that weren't actually missable with the information available at the time. Companies face liability for failing to predict outcomes that were genuinely unpredictable. The standard of care gets judged through the distorting lens of hindsight.

UCL researchers point out that juries are subject to numerous cognitive biases when deciding trials, but hindsight bias may be the most pernicious because it operates invisibly. Jurors don't realize they're judging past decisions with information that wasn't available at the time.

What's happening in your brain when you succumb to hindsight bias? Modern neuroscience is providing answers.

The reconstruction of memories isn't a bug in the system; it's a feature. Your brain is constantly updating its models of how the world works. When something unexpected happens, your cognitive systems need to integrate that new information. The most efficient way to do that? Retroactively adjust your memories to make the outcome seem more consistent with your worldview.

This process involves the interaction between your hippocampus (which encodes and retrieves memories) and your prefrontal cortex (which applies current knowledge and beliefs). Each time you recall an event, these systems work together to reconsolidate the memory, and current knowledge inevitably bleeds into the past.

There's also an emotional component. Admitting that the world is unpredictable and that you couldn't have seen something coming feels threatening. It suggests you're not in control. Psychological research shows that hindsight bias provides a comforting illusion: the world is understandable, events follow predictable patterns, and you have the wisdom to navigate future challenges.

But that comfort comes at a steep price.

Hindsight bias doesn't just distort the past. It actively damages your ability to learn and improve.

When you convince yourself you "knew all along" that something would go wrong, you don't actually learn anything useful. Real learning requires understanding what information was available, what you considered, and where your reasoning process broke down. Hindsight bias short-circuits this process by replacing genuine analysis with false certainty.

Imagine a project manager whose software launch failed. If she thinks "I knew we were understaffed," she misses the real lesson, which might have been about communication processes, technical debt, or unrealistic client expectations. Her future projects will suffer from the same problems because she learned the wrong lesson.

Once you know an outcome, you judge the people who didn't predict it far more harshly. This creates toxic organizational cultures where people are punished for reasonable decisions that happened to turn out badly, while being rewarded for lucky guesses.

Research on cognitive biases in organizations shows that hindsight bias leads to blame cultures where employees become risk-averse and hide problems rather than addressing them openly. After all, if bad outcomes mean you "should have known better," the safest move is to avoid decisions entirely.

The ultimate irony: believing you successfully predicted the past makes you overconfident about predicting the future. Studies show that people who exhibit strong hindsight bias are also more likely to make overconfident forecasts about what will happen next.

This creates a vicious cycle. You take on excessive risk because you believe you have better predictive abilities than you actually do. When things go wrong, you convince yourself you saw it coming (but chose to ignore it for some reason). This false learning reinforces your overconfidence, and the cycle continues.

The good news? Once you understand hindsight bias, you can implement strategies to counter it. These techniques won't eliminate the bias entirely, but they can significantly reduce its impact.

The single most powerful tool against hindsight bias is contemporaneous documentation. Before making a decision, write down your reasoning, what you expect to happen, what alternatives you considered, and what information you wish you had but don't.

This creates an immutable record that your future self can't revise. When you look back at the decision, you'll see what you actually thought at the time, not the sanitized version your hindsight-biased brain wants to remember.

The single most powerful tool against hindsight bias is keeping a decision journal. Write down your reasoning before you know the outcome, creating an immutable record that your future self can't revise or rewrite.

Professional investors use decision journals extensively. They record not just what they bought, but why, what concerns they had, what could go wrong, and what would change their thesis. When reviewing past investments, this contemporaneous record prevents them from fooling themselves about what they "knew."

The format doesn't matter. It could be a notebook, a voice memo, an email to yourself, or specialized software. What matters is that you capture your thinking before you know the outcome.

A pre-mortem is like a post-mortem, but before the patient dies. Before launching a project or making a major decision, gather your team and ask them to assume the initiative has failed spectacularly. Then work backward: why did it fail?

This technique forces people to imagine negative outcomes and identify potential problems while they can still be addressed. It's hindsight bias in reverse: using the power of retrospective thinking to improve prospective decision-making.

Research shows pre-mortems uncover problems that traditional planning misses because they bypass the optimism bias that typically accompanies new projects. Team members feel permission to voice concerns they might otherwise suppress.

Your brain naturally seeks information that confirms what you already believe. Actively counter this by assigning someone the role of devil's advocate or specifically searching for evidence that contradicts your current thinking.

Before you congratulate yourself for "knowing" an outcome was inevitable, force yourself to list all the reasonable ways things could have turned out differently. This exercise reminds you that the path not taken was often just as plausible as the one that actually occurred.

Structured processes with predefined criteria and checklists limit the influence of hindsight bias. When you must evaluate decisions against clear standards established before knowing the outcome, you can't simply reverse-engineer justifications.

Many organizations use decision frameworks that require documenting assumptions, identifying key uncertainties, and specifying what evidence would change the decision. This structure forces clearer thinking upfront and provides objective benchmarks for later evaluation.

The world isn't deterministic. Most outcomes involve probability, not certainty. Forecasting experts recommend thinking in terms of ranges and likelihoods rather than single-point predictions.

Instead of predicting "the stock will rise," estimate "there's a 60% chance it will rise, a 30% chance it will trade sideways, and a 10% chance it will fall significantly." This mindset acknowledges uncertainty and makes it harder to claim you "knew all along" when one of several possible outcomes occurs.

"When something with a 10% probability happens, that doesn't mean your forecast was wrong. It means the unlikely thing occurred, which happens 10% of the time."

- Probabilistic Forecasting Principles

When something with a 10% probability happens, that doesn't mean your forecast was wrong. It means the unlikely thing occurred, which happens 10% of the time. Probabilistic thinking keeps you honest about what you actually knew.

Technology and AI can help by serving as impartial judges of decision quality. Robo-advisors, for example, execute investment strategies based on predefined rules, preventing humans from second-guessing themselves based on hindsight.

Similarly, decision-support systems that log predictions and reasoning can be programmed to evaluate decisions based on the information available at the time, not on how things turned out. This separates decision quality from outcome quality, a crucial distinction that hindsight bias tends to erase.

Hindsight bias doesn't operate in isolation. It's connected to outcome bias (judging decisions by results rather than quality), the familiarity heuristic (preferring the familiar over the unknown), and various other cognitive shortcuts.

Understanding the broader landscape of cognitive biases helps you recognize when your thinking might be distorted. Just as knowing about optical illusions doesn't make them disappear but helps you compensate for them, knowing about cognitive biases allows you to build systems that work around your brain's limitations.

At its core, hindsight bias is about our discomfort with uncertainty. We want to believe the world is predictable and that we're smart enough to navigate it successfully. Admitting that luck plays a huge role in outcomes, and that many things are genuinely unknowable in advance, feels like accepting helplessness.

But there's liberation in embracing uncertainty. When you stop pretending you can predict the future or that past events were inevitable, you make better decisions. You plan for multiple scenarios instead of betting everything on your "obvious" prediction. You judge yourself and others more fairly, based on decision quality rather than outcome luck. You learn genuine lessons instead of false ones.

Evidence-based strategies for cognitive bias mitigation show that organizations that acknowledge uncertainty and focus on process over outcomes tend to outperform those that pretend everything is predictable. They create cultures where people share information honestly, admit mistakes without fear of unfair punishment, and learn from both successes and failures.

The next time you catch yourself thinking "I knew that would happen," pause. Did you really? If you'd genuinely known, what would you have done differently? What contemporaneous record exists of your prediction?

More often than not, you'll realize your certainty is an illusion, a trick your brain is playing to make the past feel more comprehensible and to make you feel more competent. And recognizing that illusion is the first step toward better judgment.

The goal isn't to eliminate hindsight bias entirely. That's probably impossible given how human memory works. The goal is to become aware of it, build systems that compensate for it, and make decisions with clear eyes about what you actually know versus what you only think you knew.

The goal isn't to eliminate hindsight bias entirely. The goal is to become aware of it, build systems that compensate for it, and make decisions with clear eyes about what you actually know versus what you only think you knew.

Because the difference between those two things - between genuine foresight and false hindsight - might be the most important distinction you can make. It's the difference between learning and self-deception, between honest judgment and unfair blame, between real expertise and empty confidence.

The past may seem obvious now. But when you were living through it, it was just as uncertain and confusing as your present moment feels today. Remember that the next time you're tempted to say "I knew it all along." You probably didn't. And that's okay. None of us did.

The future belongs to those who can sit with uncertainty, make thoughtful decisions with incomplete information, and learn genuine lessons from outcomes good and bad. That means letting go of the comforting fiction that you saw it all coming. It means admitting that you're navigating a genuinely unpredictable world, doing your best with imperfect information.

That's not a weakness. That's wisdom.

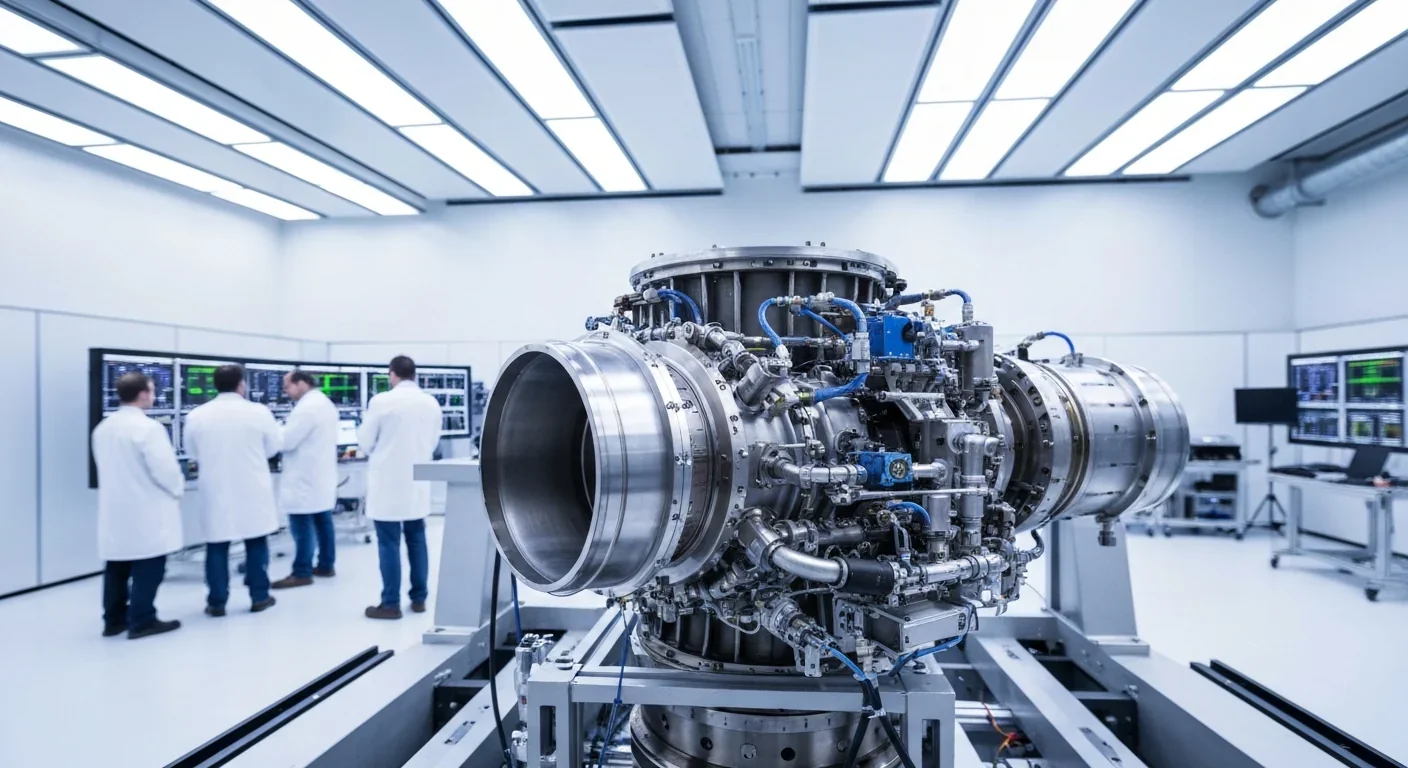

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

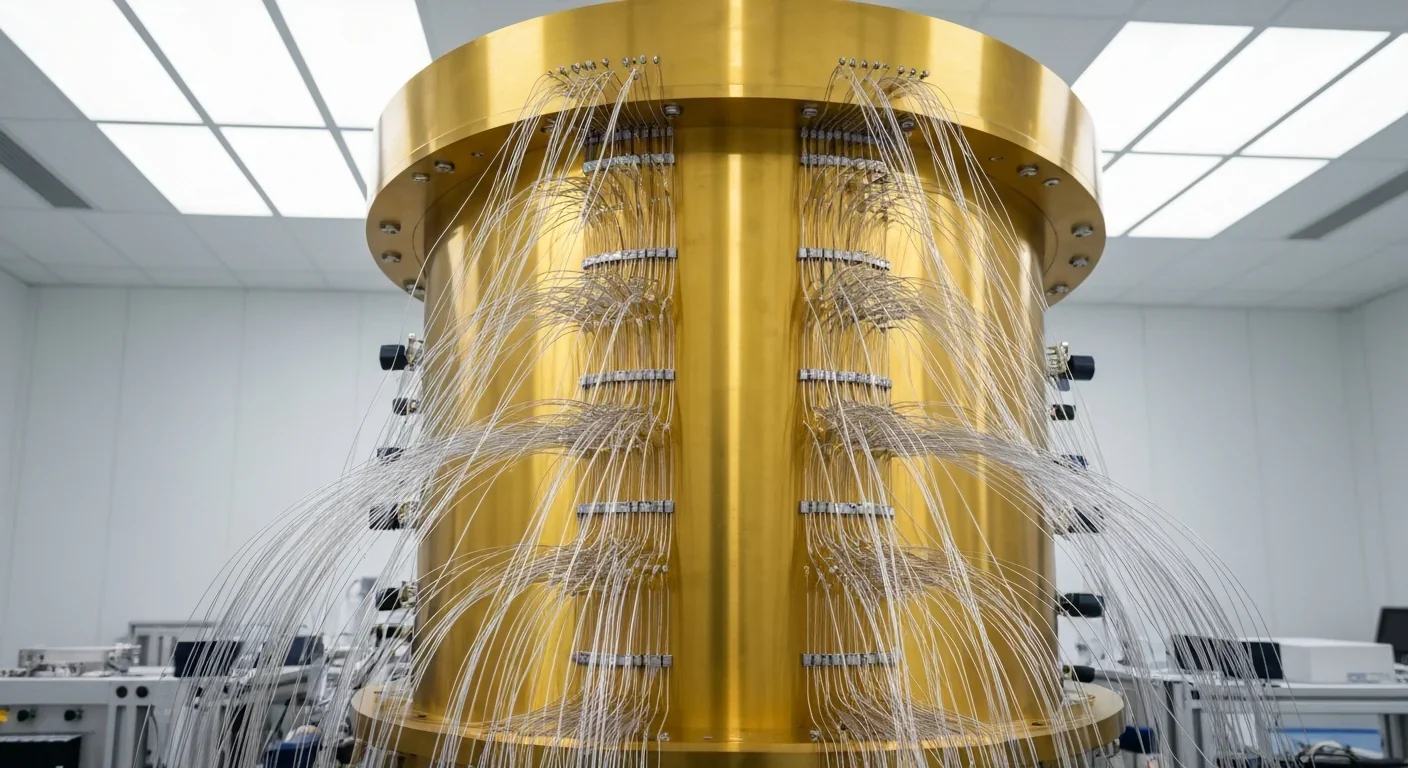

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.