Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: The ideomotor effect explains how unconscious thoughts trigger tiny muscle movements, debunking paranormal claims about Ouija boards and dowsing while revealing how our brains prepare for actions before we consciously decide to move.

Close your eyes and picture yourself picking up a coffee cup. Simple enough, right? But here's what you didn't notice: your hand just twitched. Microscopically. Involuntarily. Your brain began translating thought into motion before you even decided to move.

This is the ideomotor effect, and it's been quietly shaping human behavior for millennia. From Victorian séances to modern neurofeedback therapy, this phenomenon reveals something unsettling about the boundary between mind and body: it's far blurrier than we think.

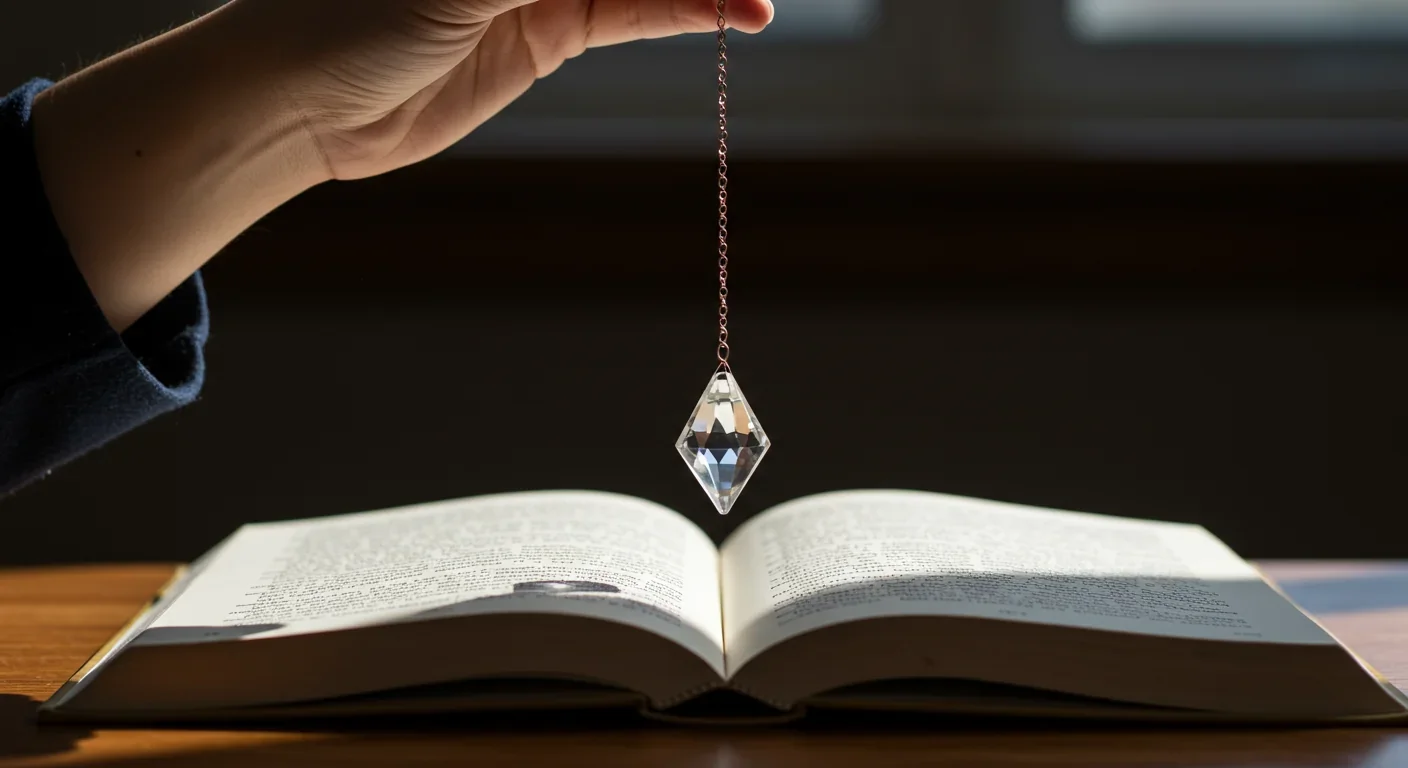

Picture a dimly lit parlor in 1850s London. A dozen hands rest on a wooden planchette. Someone asks, "Is there a spirit here?" The pointer glides across the board, spelling out Y-E-S. Gasps fill the room.

No ghosts necessary. What these Ouija board users experienced was pure neurobiology, not the supernatural. When you expect something to happen, your brain doesn't wait for conscious permission to act. It begins preparing motor commands immediately.

Scientists call this the ideomotor phenomenon: unconscious muscular movements triggered by thoughts or expectations. It's the reason dowsing rods appear to find water, why facilitated communication felt miraculous (until it was debunked), and why you can't hold a pendulum perfectly still while thinking about it swinging.

The effect is so subtle that it operates below the threshold of conscious awareness. You genuinely don't feel yourself moving. But motion-capture systems tell a different story.

The term "ideomotor" first appeared in 1852, coined by physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter while investigating how Ouija boards worked. Carpenter proposed what seemed radical at the time: ideas themselves could trigger muscular responses without conscious volition.

He wasn't alone in his curiosity. Physicist Michael Faraday conducted elegant experiments during the table-turning craze of the 1850s. People insisted spirits were moving furniture during séances. Faraday used simple lever devices to prove the participants were unconsciously pushing the tables themselves.

French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul demonstrated the same principle with pendulums. Hold a weight on a string and think about it swinging in circles. Within seconds, it will. Not because of mystical energy, but because your fingers are making microscopic movements at frequencies that match the pendulum's resonance.

By the early 20th century, psychologists like William James had integrated ideomotor theory into mainstream psychology. The paranormal explanations crumbled under scientific scrutiny, but the phenomenon itself became a window into how the brain converts thought into action.

Here's where it gets fascinating. The motor cortex, located along the top of your brain, doesn't just execute movements you consciously decide to make. It's constantly humming with preparatory activity based on what you're thinking about.

When you imagine an action, your brain activates the same neural pathways it would use to actually perform that action. Neuroimaging studies show this clearly: thinking about moving your hand lights up similar brain regions as actually moving it.

The key players in this process include:

The premotor cortex and supplementary motor area handle the planning stages. When you think "I should pick up that cup," these regions start choreographing the movement sequence before you've consciously decided to act.

The basal ganglia help select which motor programs to run and which to inhibit. When this system malfunctions, you get disorders like ideomotor apraxia, where patients can't imitate gestures on command but might spontaneously perform the same movements.

The superior posterior parietal cortex contains what researchers call the "dynamic body schema," a constantly updated mental map of your body's position and capabilities. This region translates imagined movements into motor coordinates.

What makes the ideomotor effect so intriguing is that these preparatory signals sometimes leak through into actual movement, even when you haven't given conscious approval. The threshold between "planning to move" and "moving" is more porous than our subjective experience suggests.

Let's clear up some persistent misconceptions, because the ideomotor effect has been weaponized to sell everything from ghost-hunting equipment to alternative medicine.

Myth: Dowsing rods detect underground water

Reality: Controlled tests consistently show dowsers perform no better than chance. The rods move because the person holding them unconsciously tilts their hands in response to subtle environmental cues or expectations about where water "should" be.

Myth: Ouija boards channel spirits

Reality: Multiple studies confirm that Ouija board movements come from participants, not external forces. When users are blindfolded and the board is secretly rotated, the planchette spells gibberish. The effect depends entirely on visual feedback.

Myth: Facilitated communication allows nonverbal individuals to type complex messages

Reality: This technique, where a facilitator guides a disabled person's hand over a keyboard, has been thoroughly debunked. Tests show the messages come from the facilitator, not the client. It's a tragic example of the ideomotor effect causing false hope.

Myth: Applied kinesiology can diagnose illness through muscle testing

Reality: When practitioners test muscle strength while a patient holds various substances, the results reflect the practitioner's expectations, not the patient's health status. Blinded tests eliminate the effect entirely.

The pattern is consistent: any practice that requires someone to hold an object or make subtle movements while thinking about specific outcomes is vulnerable to ideomotor influence.

Strip away the pseudoscience, though, and the ideomotor effect has genuine therapeutic applications. Hypnotherapists have used ideomotor signaling for decades as a communication tool during trance states.

The technique works like this: a therapist asks a patient's unconscious mind to answer questions using finger movements. "If the answer is yes, your index finger will lift. If no, your thumb." Patients report their fingers moving "by themselves" in response to questions they couldn't consciously answer.

Is this really the unconscious mind communicating? Maybe. Or it could be conscious thoughts producing ideomotor responses below the threshold of perceived agency. Either way, it sometimes helps patients access information or feelings they're struggling to articulate directly.

Recent neuroscience research has begun mapping what happens in the brain during hypnotic ideomotor suggestions. When a hypnotized subject is told "your arm is becoming lighter and will lift on its own," brain activity shows reduced connectivity in areas associated with sense of agency. The movement feels involuntary because the normal neural signatures of intentional action are suppressed.

Physical therapists and osteopaths also use variations of ideomotor principles in techniques like fascial unwinding, where they follow the subtle, unconscious movements of a patient's body to release tension patterns.

The difference between legitimate and fraudulent applications comes down to honesty about mechanism and outcome. Ethical practitioners understand they're working with unconscious motor responses, not supernatural forces or definitive diagnostic tools.

Now we're entering genuinely futuristic territory. If thoughts can produce measurable physical movements, what happens when we amplify those signals?

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are already doing this. Paralyzed patients can control robotic arms using motor imagery - they think about moving their arm, and sensors detect the neural activity in their motor cortex. The thought pattern is similar enough to an actual movement command that software can decode the intention.

This is the ideomotor effect scaled up and digitized. Instead of producing microscopic finger twitches, the brain's preparatory activity drives prosthetics or computer cursors.

Neurofeedback training uses similar principles. Patients learn to control specific brain activity patterns by receiving real-time feedback. Some researchers are exploring whether we can train people to enhance or suppress ideomotor responses deliberately.

In sports psychology, understanding the ideomotor effect has influenced mental rehearsal techniques. Athletes who vividly imagine performing movements show measurable improvements in actual performance, partly because mental practice activates the same motor pathways as physical practice.

Even our understanding of consciousness is shifting. The readiness potential - neural activity that begins before we consciously decide to move - was famously studied by Benjamin Libet. His work suggested that unconscious brain processes initiate actions before conscious awareness kicks in. This remains controversial, but it highlights how the boundary between voluntary and involuntary movement is more complex than everyday experience suggests.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: our brains are primed to see patterns and agency where none exist. The ideomotor effect exploits this tendency perfectly.

When you're using a Ouija board, you're not consciously pushing the planchette. The movements are real but unintended. So your brain constructs the most compelling available explanation: an external force must be moving it. This interpretation feels more plausible than "my unconscious mind is guiding my hands based on letter combinations I'm not aware of expecting."

This is why paranormal beliefs persist despite debunking. Victorian spiritualists weren't stupid or dishonest (mostly). They were experiencing genuine phenomena and interpreting them through the conceptual frameworks available in their culture. The movements were real. The explanation was wrong.

The same pattern appears in modern contexts. People "muscle test" supplements and swear they can feel which ones their body needs. Dowsers find water at rates barely above chance but remember their hits and forget their misses. The ideomotor effect provides the physical experience that confirmation bias then reinforces.

So what do we do with this knowledge? For starters, we can be more skeptical of practices that depend on subtle, unconscious movements to deliver important information. If someone claims to diagnose your health issues by testing muscle strength, find a different practitioner.

We can also harness the effect deliberately. Visualization techniques in therapy and sports aren't pseudoscience - they work because mental imagery activates motor systems. The key is understanding the mechanism without overinterpreting the results.

Perhaps most importantly, we can hold this as a humbling reminder that our conscious minds aren't quite as in charge as they feel. A significant amount of our behavior originates in neural processes we never directly experience. The ideomotor effect is just one example of unconscious influence made visible.

Your brain is constantly preparing for actions you might take, running simulations, priming motor pathways. Most of this activity stays subliminal. But occasionally, under the right conditions, those whispers of intention become visible movements. Not because spirits are moving you, but because your mind is already in motion, translating thought into potential action.

The next time you pick up that coffee cup, pay attention. The movement started long before you reached out your hand. And that invisible preparation, that motor hum beneath conscious awareness, is what the ideomotor effect allows us to glimpse.

We're not possessed by ghosts. We're inhabited by our own unconscious processes, endlessly rehearsing, planning, and occasionally - just occasionally - letting those plans slip into the physical world before we've given the official go-ahead.

And honestly? That's far more fascinating than any séance.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

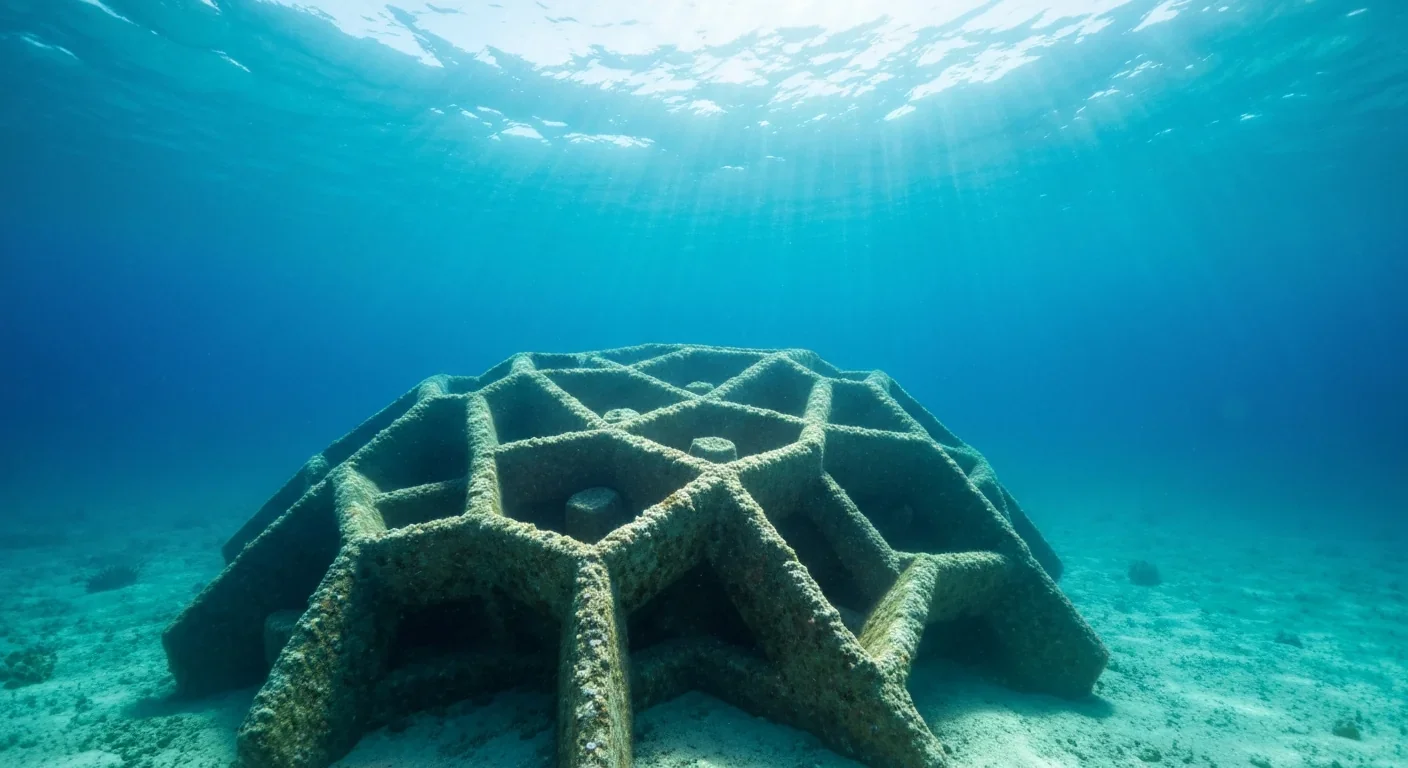

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

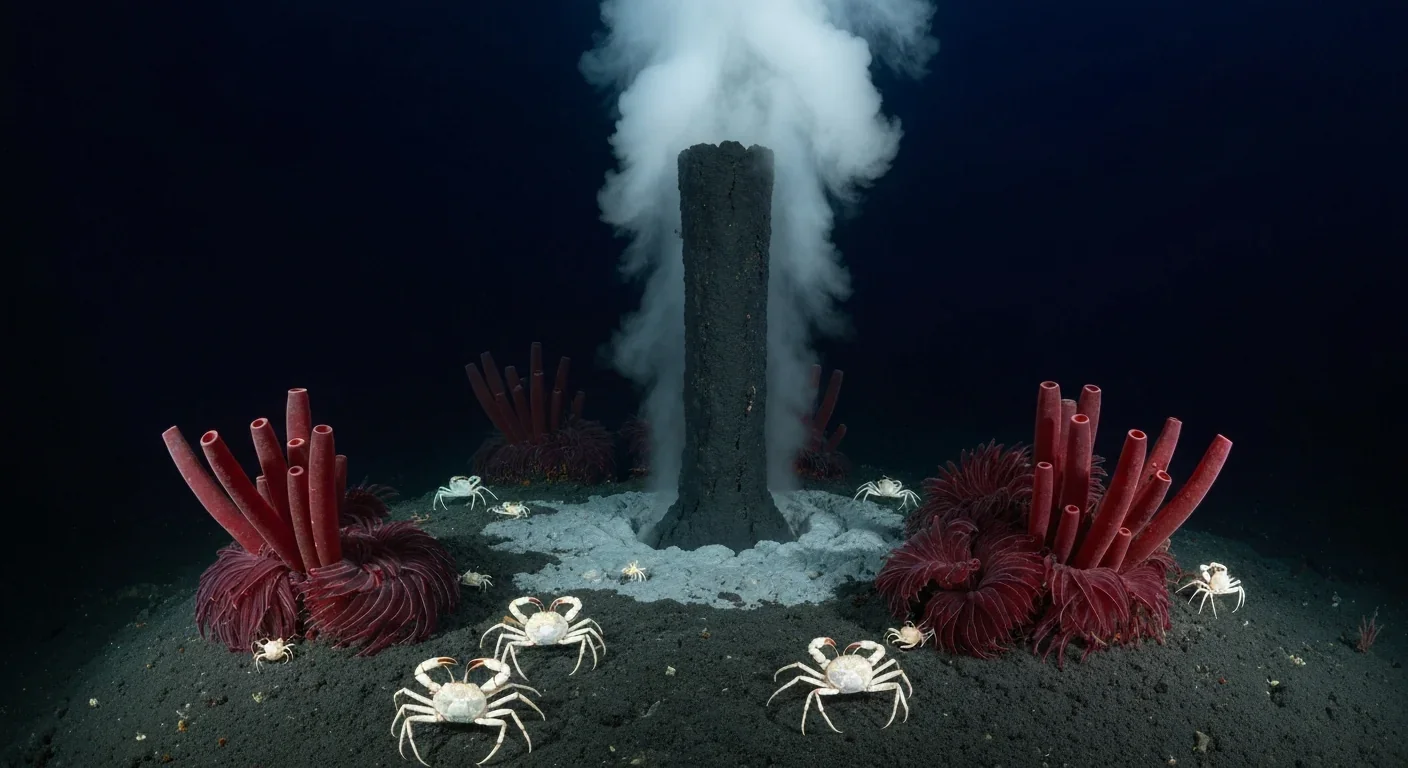

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

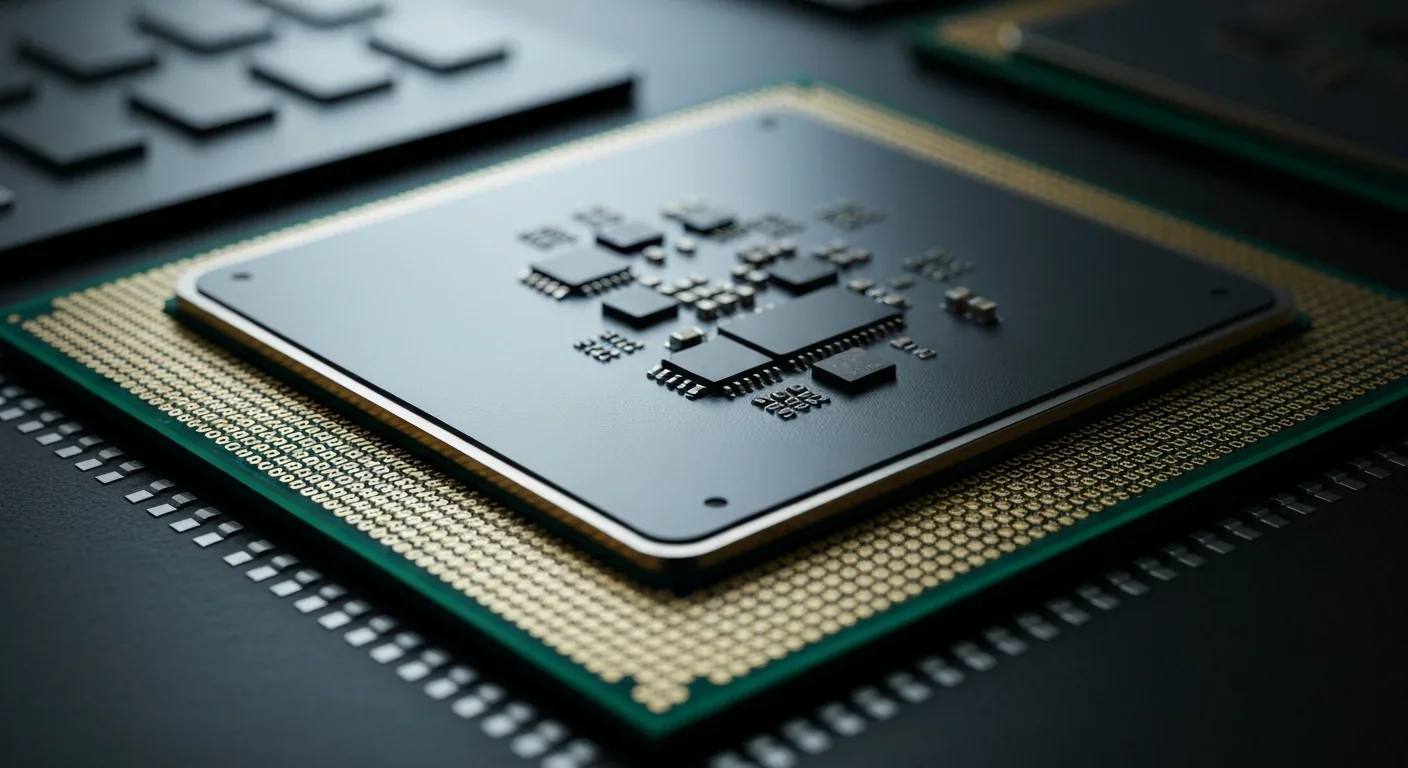

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.