The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The illusion of control leads humans to believe they can influence random events, from casino dice to stock markets. This cognitive bias, hardwired into our brains, affects everyone from gamblers to professional traders, creating false confidence in our ability to control chance.

Picture yourself at a craps table in Las Vegas. The player next to you grabs the dice, shakes them vigorously, and whispers "Come on, seven!" before hurling them down the felt with considerable force. When asked why the aggressive throw, they explain they need high numbers. Later, when hoping for a low roll, that same player gently releases the dice with a soft underhand toss. This behavior seems ridiculous when you think about it rationally. The dice don't care how hard you throw them. Physics and probability determine the outcome, not the force of your wrist or your whispered prayers. Yet this scene plays out thousands of times daily in casinos worldwide, and the person throwing those dice genuinely believes their actions influence the outcome.

This belief represents one of humanity's most pervasive cognitive biases: the illusion of control. It's the tendency to overestimate our ability to influence events that are actually governed by chance, and it affects far more than just casino gambling. From stock trading floors where professionals claim they can "feel" market movements, to sports fans who wear lucky jerseys believing it helps their team win, humans consistently see patterns and control where only randomness exists.

The illusion of control wasn't formally recognized by science until 1975, when Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer conducted a series of groundbreaking experiments that would forever change how we understand human decision-making. Langer's genius lay not in discovering that people sometimes feel they control random events, but in systematically demonstrating how universal and predictable this tendency is.

In one of her most famous experiments, Langer set up a lottery with office workers. Some participants chose their own lottery tickets from a box, while others were simply handed tickets at random. When researchers later offered to buy back these tickets or trade them for tickets in a lottery with better odds, something remarkable happened. Those who had chosen their own tickets demanded significantly more money to sell them back, around four times as much as those given random tickets. Some refused to trade at all, even when offered tickets with mathematically superior chances of winning.

The simple act of choosing a lottery ticket, even from a box of random options, makes people value it four times more than an identical ticket they didn't choose. This demonstrates how even minimal involvement creates powerful illusions of control.

Think about this for a moment. The act of choosing a ticket from a box cannot possibly affect whether those numbers will be drawn. Yet the simple act of selection created such a powerful sense of ownership and control that people literally valued their self-selected tickets as more likely to win. This wasn't just one or two people, this was a consistent pattern across multiple studies with different populations.

Langer identified several factors that amplify our illusion of control, which she called "skill cues." These include having choices to make, competing against others, becoming familiar with a task, and being actively involved in decisions. When any of these elements appear in a random situation, our brains automatically shift into skill mode, convinced we can influence the outcome through our actions or decisions.

Recent neuroscience research has revealed something even more fascinating: our brains literally cannot tell the difference between rewards we earn through skill and those we receive through luck. Brain imaging studies show that when someone wins at a slot machine, pulling the lever and watching the reels spin, the same reward centers light up as when they succeed at a challenging video game that actually requires skill.

The ventral striatum, a key component of the brain's reward system, releases dopamine whether you've just solved a complex puzzle through intelligence or won a random lottery draw. This neurological response explains why the illusion of control is so persistent and difficult to overcome. Your brain is essentially lying to you, providing the same chemical reward for lucky outcomes as for genuine achievements.

This neurological quirk likely evolved for good reasons. Our ancestors who assumed they had some control over their environment, who believed their actions mattered, were more likely to keep trying when faced with challenges. The farmer who believed their rain dance might help probably planted more crops than the one who felt helpless against nature's whims. In a world where effort often does influence outcomes, a bias toward perceiving control served our species well.

But in modern environments filled with random events dressed up as skill-based challenges, from day trading apps designed to feel like video games to slot machines that let you "stop" the reels, this same neural wiring becomes a vulnerability. The primitive parts of our brain can't distinguish between the rush of making a successful stock trade and the satisfaction of building something with our hands.

"The brain's reward centers are activated similarly for both skill-based and luck-based successes. Your neurological system literally cannot tell the difference between earning a reward and randomly receiving one."

- Neuroscience Research on Reward Processing

Humans are pattern-recognition machines. This ability allowed our ancestors to identify which plants were safe to eat, predict weather changes, and recognize faces in the dark. But this same pattern-seeking behavior creates problems when applied to truly random events. Psychologists call the tendency to see meaningful patterns in random data "apophenia," and it's the foundation upon which the illusion of control is built.

Consider the gambler who notices that slot machines near the entrance seem to pay out more often. They develop elaborate theories about why this might be true. Maybe casinos put looser machines there to attract players with the sound of winning. Perhaps the machines get more play and are therefore "warmed up." They start exclusively playing entrance machines, convinced they've discovered a system.

In reality, any perceived pattern is pure coincidence. Modern slot machines use random number generators that produce millions of combinations per second. The location of the machine, the time of day, how long since the last payout, none of these factors influence the odds. Yet once someone believes they've found a pattern, confirmation bias kicks in. They remember every win at an entrance machine and forget the losses, reinforcing their false belief.

This pattern-seeking gone wrong extends far beyond casinos. Stock market investors convince themselves they can predict movements based on chart patterns that are essentially random walks. Sports fans believe their team is "due" for a win after a losing streak, as if probability has memory. Parents swear by lucky socks that helped their child ace a test, forgetting all the times those same socks were worn during failures.

Nowhere is the illusion of control more studied, measured, and unfortunately exploited than in gambling environments. Modern casinos have become sophisticated laboratories for triggering and amplifying this bias. Every design element, from the ability to choose your slot machine to the option to pull a lever instead of pressing a button, is calculated to increase feelings of control.

Research shows that when people can pick their own lottery numbers rather than receiving a random quick-pick, they bet more money and play more often, despite identical odds. When slot machines show "near misses" where two cherries line up but the third falls just short, players experience an increased sense of control, believing they almost won through their timing or technique. These near misses activate the same brain regions as actual wins, creating an addictive loop of almost-success that feels like it's within the player's control to complete.

The craps example from our opening isn't just anecdotal. Studies have documented that players consistently throw dice harder when wanting high numbers and softer for low numbers. When researchers asked these players why they do this, many insisted it helps, even when shown mathematical proof that dice outcomes are random regardless of throwing force. The physical involvement, the ability to influence the dice's initial trajectory, creates an irresistible feeling of control over the ultimate outcome.

Even more troubling, research with problem gamblers shows they experience stronger illusions of control than casual players. They're more likely to believe in hot streaks, lucky machines, and personal systems. This isn't because they're less intelligent. Studies found no correlation between reasoning ability and susceptibility to the illusion. Instead, problem gamblers seem to have stronger emotional and motivational drives that override logical thinking.

Near-miss events in slot machines activate the same brain regions as actual wins, creating an addictive cycle where players feel they're just one adjustment away from success, despite outcomes being entirely random.

If you think the illusion of control only affects desperate gamblers in smoky casinos, think again. Some of the most educated, analytically trained professionals in the world fall prey to the same bias when trading stocks, bonds, and derivatives. The trading floor might seem worlds away from a casino floor, but the psychological dynamics are remarkably similar.

A fascinating study examined professional traders in the City of London, individuals with advanced degrees and years of experience analyzing markets. Researchers showed them random price charts, completely generated by computer with no underlying pattern or logic. The traders were asked to predict future movements and rate their confidence in their predictions. Not only did these professionals claim to see clear patterns in the random data, but those who reported the strongest feelings of control actually performed worse in real trading scenarios.

The parallels to gambling are striking. Day traders who execute frequent trades, choosing exact entry and exit points, feel more in control than those who buy and hold index funds. Yet study after study shows frequent traders underperform the market by significant margins, often by 5-8% annually after accounting for transaction costs. The very act of making decisions, of being involved and active, creates an illusion of control that leads to worse outcomes.

Professional fund managers exhibit similar biases. Despite overwhelming evidence that very few actively managed funds beat passive index funds over time, managers remain convinced of their ability to pick winners. They attribute successful trades to skill while dismissing failures as bad luck or unforeseeable events. This self-attribution bias reinforces the illusion of control, creating a feedback loop where random success breeds overconfidence.

The rise of retail trading apps has democratized these biases. Modern trading platforms are deliberately designed to trigger feelings of control. They offer endless technical indicators, drawing tools, and real-time data that make users feel like informed decision-makers. The ability to swipe to trade, to set precise limit orders, to choose from thousands of stocks, all create skill cues that trigger the illusion of control. The result? The average retail trader loses money, even in bull markets.

Sports provide another fertile ground for studying the illusion of control, particularly through the famous "hot hand" phenomenon. Watch any basketball game and you'll hear commentators talk about players who are "on fire" or "in the zone." Teammates feed the ball to someone who's made several shots in a row, convinced they're more likely to make the next one. Fans and players alike believe in momentum, clutch genes, and the ability to will victory through determination.

Yet when researchers analyzed thousands of basketball shots, they found no evidence for the hot hand. A player who has just made three shots in a row is no more likely to make the fourth than their overall average would predict. The perception of hot streaks comes from our pattern-seeking brains latching onto random clusters of success. We notice and remember the times when success continues but forget the many times when hot streaks suddenly go cold.

Athletes themselves strongly resist this evidence. Professional players insist they can feel when they're in the zone, when everything clicks and they have special control over outcomes. This belief might actually be beneficial for performance through confidence effects, but it's still an illusion when it comes to statistical reality. The player hasn't gained magical control over physics. They're experiencing the same random variation everyone faces, just interpreted through the lens of perceived control.

The illusion extends beyond players to coaches, who believe they can influence games through strategic timeouts or motivational speeches at just the right moment, and to fans who wear lucky jerseys or perform elaborate rituals. Sports bars are filled with people who genuinely believe their presence, their cheers, or their superstitious behaviors influence games being played hundreds of miles away.

"A player who has just made three shots in a row is no more likely to make the fourth than their overall average would predict. The hot hand is a compelling illusion created by our pattern-seeking minds."

- Statistical Analysis of Basketball Shooting

Before we dismiss the illusion of control as purely negative, it's worth considering its benefits. Moderate levels of perceived control correlate with better mental health, higher motivation, and greater persistence in the face of challenges. The entrepreneur who believes they can beat the odds might work harder and occasionally succeed where a purely rational person would never try.

Studies on depression reveal something called "depressive realism." People with depression often show less illusion of control than healthy individuals. They more accurately assess their ability to influence outcomes, which sounds positive but may contribute to feelings of helplessness and lack of motivation. Sometimes, a little illusion keeps us going when pure rationality would lead to paralysis.

The key is finding balance. The illusion of control becomes problematic when it leads to excessive risk-taking, financial losses, or addictive behaviors. The problem isn't feeling you have some influence over your life, it's dramatically overestimating that influence in situations governed by chance. A healthy person might buy an occasional lottery ticket for fun while understanding the terrible odds. Someone deep in the illusion might spend their rent money on tickets, convinced their system or feeling makes them different from other players.

Consider how the illusion of control affects different domains. In creative work or athletic training, believing you have control motivates practice and improvement. Even if success involves luck, effort still matters. But in pure games of chance or market speculation, the illusion of control provides no benefit and potentially severe costs. Recognizing which situation you're in becomes crucial.

So how can we maintain beneficial feelings of agency while avoiding the pitfalls of illusory control? The first step is awareness. Simply knowing about this bias doesn't make you immune, but it creates a checkpoint in your decision-making process. When you feel strongly that you can influence an outcome, pause and ask: "Is this genuinely a situation where my actions matter, or am I seeing control where only randomness exists?"

Researchers have identified several effective strategies for reducing harmful illusions of control. Pre-commitment strategies work particularly well. Setting strict rules before entering situations that trigger the illusion, like deciding on gambling limits or using automatic investing rather than active trading, removes the opportunity for biased decision-making in the moment.

Education about probability and statistics helps, though not as much as you might expect. Even statistics professors buy lottery tickets and make poor investment decisions. The emotional pull of perceived control often overwhelms intellectual understanding. More effective is what psychologists call "implementation intentions", specific if-then rules that bypass in-the-moment reasoning. "If I feel like I've figured out the pattern in roulette, then I will immediately leave the casino."

Some innovative approaches involve redesigning environments to reduce triggers for illusory control. For instance, some investment firms now offer interfaces that discourage frequent trading by showing long-term performance rather than daily fluctuations, removing the constant decision points that create feelings of control. Casinos, unsurprisingly, move in the opposite direction, adding more choices and interaction points to amplify the illusion.

Mindfulness and metacognition training show promise. By developing the ability to observe our own thoughts and recognize when we're constructing false narratives of control, we can catch ourselves before acting on these illusions. This doesn't mean becoming paranoid about every decision, but rather developing a healthy skepticism about our ability to influence random events.

The illusion of control ultimately stems from a deep discomfort with uncertainty. Humans crave predictability and agency. We want to believe our actions matter, that we're not merely leaves blown by the winds of chance. This desire for control is so fundamental that our brains will manufacture it even where it doesn't exist, turning random noise into meaningful signals.

In our modern world, where so much feels uncertain and beyond our control, from economic fluctuations to global pandemics to technological disruption, the allure of perceived control grows stronger. We refresh social media obsessively as if we can influence world events through awareness. We check stock prices hourly as if watching somehow provides control. We develop elaborate routines and superstitions to ward off the anxiety of powerlessness.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a massive natural experiment in how humans respond to loss of control. Some people created elaborate theories about government control and hidden patterns, desperately seeking some framework that restored a sense of predictability and agency. Others threw themselves into controlling what they could, from sourdough baking to home organization, finding comfort in small domains of genuine influence.

Understanding the illusion of control doesn't mean embracing nihilism or learned helplessness. Many aspects of life do respond to our efforts. Education improves career prospects. Exercise improves health. Kindness strengthens relationships. The challenge is distinguishing genuine influence from illusory control, focusing our energy where it actually makes a difference while accepting uncertainty elsewhere.

The greatest paradox: by recognizing and accepting the limits of our control, we gain something more valuable - the wisdom to focus our efforts where they truly matter and the peace to accept what we cannot change.

As we navigate an increasingly complex world, where algorithms make decisions we don't understand and global events cascade in unpredictable ways, the ability to accurately assess our own agency becomes more crucial. The person who recognizes the illusion of control can make better financial decisions, avoid gambling addiction, and maintain mental health in the face of uncertainty. They can channel their need for control into domains where effort actually matters while accepting randomness with equanimity.

The dice will fall as physics determines, regardless of how hard we throw them. Stock prices will fluctuate based on countless factors beyond our analysis. Sometimes we'll win when we had no control, and sometimes we'll lose despite our best efforts. Accepting this reality doesn't diminish us. Instead, it frees us to focus on what we can genuinely influence: our responses, our preparation, our relationships, and our character. The greatest control we have is not over external events but over ourselves, and recognizing the boundary between the two might be the most important skill we can develop.

Perhaps the ultimate irony is that by giving up the illusion of control, we gain something more valuable: the wisdom to know when our actions matter and the serenity to accept when they don't. In a universe of uncertainty, that's the closest thing to real control any of us can achieve.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

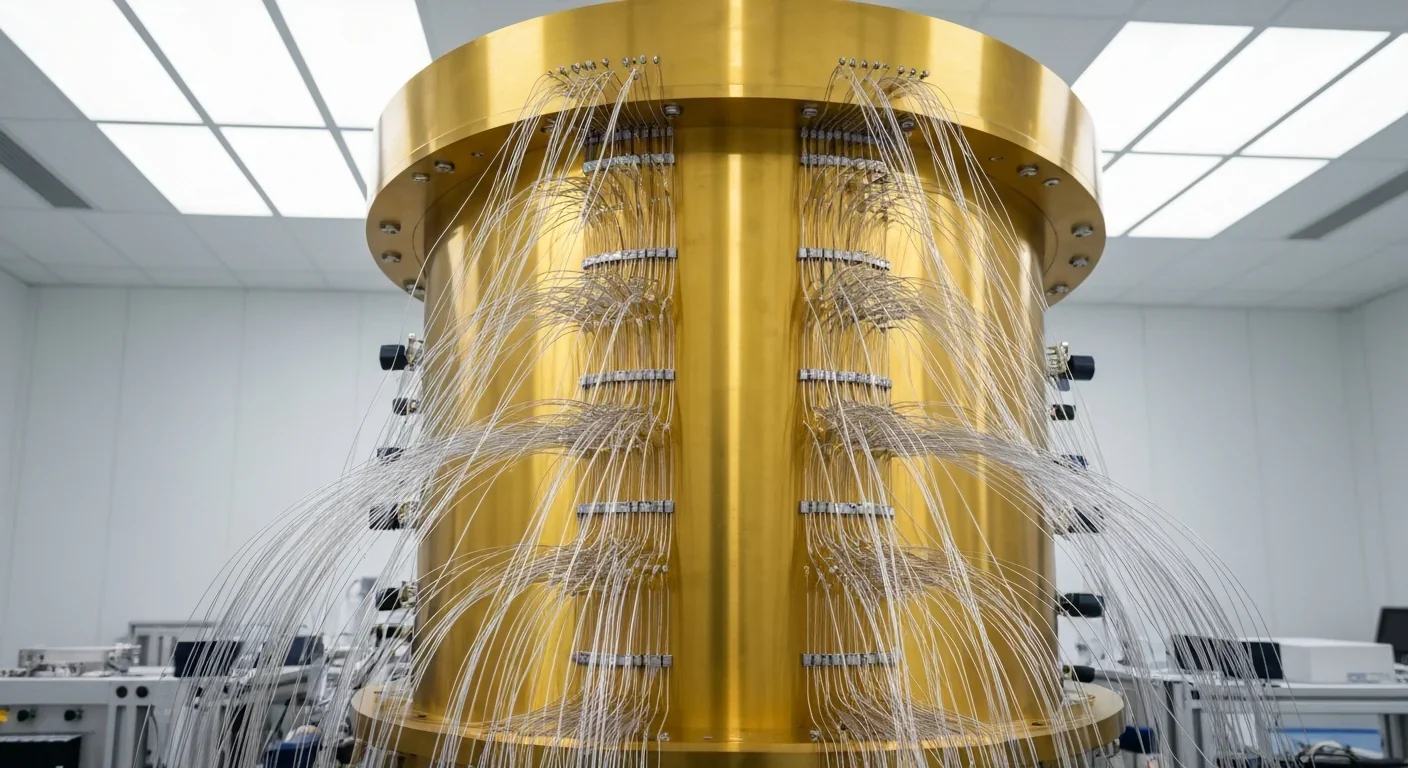

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.