Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Your brain retrieves memories that match your current mood, creating feedback loops that can reinforce both positive and negative emotional states. Understanding this mood congruence effect reveals why depression is hard to escape and provides practical strategies to interrupt negative cycles.

Have you ever noticed how a bad day makes you remember every mistake you've ever made, while a good mood floods you with positive memories? That's not random. Your brain is running a sophisticated filtering system called the mood congruence effect, and it's shaping your reality more than you realize.

The mood congruence effect is simple but powerful: when you're happy, your brain preferentially retrieves happy memories. When you're sad, it digs up sad ones. This isn't just about feeling nostalgic or dwelling on the past. Research shows this mechanism actively reinforces your current emotional state, creating feedback loops that can either lift you up or pull you down.

For people struggling with depression and anxiety, understanding this effect isn't academic - it's potentially life-changing. The cycle of negative mood triggering negative memories, which then deepen negative mood, helps explain why these conditions are so hard to escape.

The mood congruence effect emerged from research in the 1980s, though scientists had long suspected emotions influenced memory. Gordon Bower's groundbreaking work at Stanford University provided the first systematic evidence. His experiments revealed that people in induced happy moods recalled approximately twice as many positive life events compared to people in sad moods.

But Bower went further. He developed the associative network theory, proposing that emotions act as nodes in a vast neural network. When you activate an emotional node through your current mood, it spreads activation to related memories, making them easier to retrieve. Think of it like turning on one Christmas light in a string - the electrical current flows to connected bulbs.

This wasn't just a laboratory curiosity. Follow-up research revealed the effect was strongest for personally meaningful events - exactly the memories that shape our self-concept and worldview.

Your brain doesn't just remember your past - it curates which version of the past you see, based entirely on how you feel right now.

The mood congruence effect isn't mysterious once you understand the machinery. At the center sits the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep in your brain that acts as your emotional processing hub. When you experience something emotionally charged, the amygdala doesn't just register the feeling - it chemically tags the memory being formed.

Recent neuroscience research published in the Journal of Neuroscience revealed something remarkable: the amygdala's initial response to emotional events creates stable patterns in the neocortex that strengthen with repetition. Each time you recall an emotional memory, you're not just remembering - you're reinforcing the neural pathways that connect that emotion to that memory.

The amygdala coordinates with the hippocampus (your memory formation center) and the prefrontal cortex (your executive control center) to create what neuroscientists call "emotional memory tagging." When you're in a particular emotional state, your brain literally becomes better at retrieving memories tagged with similar emotions.

But there's more happening chemically. Neurotransmitters like norepinephrine and serotonin play crucial roles in memory retrieval. When you're sad, your serotonin levels drop, making it harder to access positive memories and easier to recall negative ones. When you're happy, the opposite happens. Your brain chemistry isn't just responding to your mood - it's actively shaping what you remember.

One surprising finding: what you choose to remember matters more than the emotion itself. Intention can override emotion. If you deliberately focus on positive aspects of experiences, even when you're feeling down, you can begin to retrain your retrieval patterns.

People often confuse mood congruence with state-dependent memory, but they're different phenomena with different implications. State-dependent memory means you remember things better when you're in the same state (emotional or physical) as when you learned them. If you studied while anxious, you might recall more during an anxious test.

Mood congruence doesn't care about your state during encoding. It only cares about emotional valence - positive or negative. When you're sad now, you'll recall sad memories regardless of your mood when those memories formed. You might have been happy at your graduation, but if you're depressed today, you might recall the moment you tripped on stage instead of receiving your diploma.

This distinction matters for treatment. State-dependent effects suggest recreating emotional contexts, while mood congruence suggests interrupting emotional patterns.

At first glance, mood congruence seems like a design flaw. Why would evolution give us a system that reinforces negative moods by dredging up negative memories? The answer lies in adaptation and prediction.

When our ancestors faced threats, negative emotions like fear or anxiety signaled danger. In those moments, rapidly accessing memories of past dangers - what went wrong, what to avoid - provided survival advantages. If you're afraid, remembering past threats helps you identify and respond to current ones.

Similarly, positive moods signal safety and opportunity. When you're happy, your environment is likely supportive, making it useful to recall past successes and positive social interactions. This helps you capitalize on good circumstances and build on what worked before.

The problem is our modern environment. We evolved for immediate physical threats - predators, hostile tribes, scarce resources. Today's stressors - work deadlines, social media comparisons, financial worries - activate the same systems but persist indefinitely. The mood congruence effect becomes maladaptive when chronic stress or depression keeps us locked in negative retrieval patterns.

"The reason mood congruence feels inescapable is because it creates internally consistent narratives. Every memory your brain serves up confirms what you already feel."

- Dr. Gordon Bower, Stanford University

For people with clinical depression, mood congruence transforms from a feature into a bug. Depression creates persistently low mood, which triggers retrieval of negative memories, which deepens the depression, which triggers more negative memories. It's a self-reinforcing downward spiral.

Research on autobiographical memory in depression reveals another troubling pattern: depressed individuals often develop "overgeneral" memory - they recall vague summaries rather than specific episodes. Instead of remembering "the time I gave a great presentation at the conference in Chicago," they recall "I've always been anxious about public speaking." This overgeneralization strips away positive specifics while emphasizing negative patterns.

The amygdala's role becomes particularly problematic in depression. Brain imaging studies show hyperactive amygdala responses to negative stimuli in depressed individuals, creating stronger emotional tags on negative memories. Combined with reduced prefrontal cortex activity (which normally helps regulate emotion), the result is a brain that's extremely efficient at recalling why life is terrible.

Anxiety follows a similar pattern. Anxious moods prime memories of past threats and failures, reinforcing the belief that danger lurks everywhere. This helps explain why reassurance rarely helps anxious people - their memory systems are literally designed to ignore contradictory positive evidence.

One study found that depressed individuals showed biased belief updating, integrating mood-congruent information more readily than mood-incongruent information. When depressed, you don't just remember more negative events - you also give them more weight in shaping your worldview.

The mood congruence effect isn't confined to clinical populations. It shapes everyday decision-making, relationships, and self-perception for everyone.

Job interviews provide a telling example. If you're anxious before an interview, you'll more easily recall past professional failures and embarrassing moments. This floods your working memory with exactly the wrong information, undermining confidence and performance. The interviewer asks about your strengths, and your brain serves up memories of weaknesses.

Romantic relationships are particularly vulnerable. After a fight with your partner, mood congruence makes you remember every past argument and disappointment while forgetting tender moments and shared joys. This temporary but powerful bias can escalate conflicts and damage relationships unnecessarily.

Even eyewitness testimony gets distorted by mood congruence. Witnesses recalling traumatic events often struggle to access positive or neutral details because their emotional state during testimony biases retrieval toward threat-related information. This has serious implications for criminal justice.

The effect shapes long-term life decisions. When evaluating whether to change careers, move cities, or end relationships, your current mood heavily influences which memories feel relevant and important. Making major decisions during emotional extremes practically guarantees distorted input.

Social media amplifies mood congruence. Scrolling while sad makes negative posts jump out while positive ones barely register. This creates the illusion that everyone else is either having a better time (envy) or that the world is uniformly terrible (validation of negativity). The algorithm learns your patterns and serves up more mood-matching content, deepening the spiral.

Making major life decisions during emotional extremes is like trying to read a map while wearing colored glasses - everything you see is tinted by your current state.

Not all negative emotions create equal memory biases. Research comparing emotional states reveals important distinctions in how different moods shape retrieval.

Sadness creates the strongest mood congruence effects, likely because sadness involves rumination and self-focus. When you're sad, you naturally reflect on the past, giving mood-congruent memories more opportunities to surface.

Anxiety shows different patterns. Rather than recalling generally negative events, anxious moods specifically prime threat-related memories - times you were embarrassed, endangered, or rejected. The brain treats current anxiety as a signal to review past threats for useful information about what to avoid.

Anger biases memory toward injustices and frustrations. When you're angry at someone, you recall every past slight with perfect clarity while forgetting acts of kindness. This serves the evolutionary purpose of tracking who might be unreliable or hostile.

Interestingly, positive moods show weaker congruence effects than negative ones. When you're happy, you still access some negative memories - your brain maintains broader perspective. This asymmetry makes sense evolutionarily: false positives about danger are survivable, but false negatives can be fatal. Better to err toward remembering threats.

Disgust creates particularly specific memory biases. Research on eating disorders shows that disgust-related cues trigger vivid, specific memories related to body image and food, demonstrating how different emotions activate different memory networks.

Understanding mood congruence has revolutionized approaches to depression and anxiety treatment. The key insight: you can't wait for mood to improve before changing thought patterns. You need to interrupt the mood-memory loop directly.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) explicitly targets mood congruence through mood repair strategies. Therapists teach clients to deliberately access positive memories even when feeling negative. This isn't toxic positivity - it's systematic retraining of retrieval patterns. By repeatedly practicing positive recall during neutral or slightly negative moods, people can weaken automatic negative retrieval.

Autobiographical memory specificity training represents another promising approach. Instead of vague negative generalities ("I always fail"), patients practice recalling specific positive episodes with sensory details. "I remember presenting my project in March, wearing my blue shirt, and Sarah said it changed how she thought about the problem." Specificity breaks overgeneralization.

Behavioral activation - deliberately engaging in positive activities even when unmotivated - works partly by creating new positive memories and improving mood, which then makes existing positive memories more accessible. It's a strategic intervention in the feedback loop.

Mindfulness-based approaches work differently. Rather than changing memory content, they change your relationship to memories. When you're sad and negative memories arise, mindfulness trains you to observe them without getting pulled into rumination. You notice "my brain is showing me sad memories" rather than "my life is terrible."

Pharmacological interventions like SSRIs address mood congruence by modulating neurotransmitters involved in memory retrieval. As serotonin levels normalize, the bias toward negative memory retrieval weakens. This creates space for therapy to build new patterns.

Emerging interventions include cognitive training programs that explicitly train positive retrieval through gamified exercises. These show promise for people who struggle with traditional talk therapy.

"You can't wait for your mood to improve before changing your thought patterns. You need to interrupt the mood-memory loop directly."

- Clinical Psychology Research

You don't need clinical depression to benefit from managing mood congruence. Here are evidence-based strategies anyone can use:

Before major decisions, stabilize your mood. Don't quit your job on a bad day or commit to a big purchase while euphoric. Wait 24-48 hours in a neutral state before finalizing decisions that require accurate memory retrieval about past patterns.

Keep a "complete picture" journal. When reviewing your day, deliberately record both positive and negative events, even if your mood wants to emphasize one. This creates a balanced record you can review later, counteracting your current state's retrieval bias.

Use external memory aids. Photos, saved messages, and written records provide emotion-independent access to your past. When depressed, look at photos from genuinely happy times. Your brain might not spontaneously retrieve those memories, but the photos force activation of positive neural networks.

Practice deliberate positive recall. Set a daily practice: spend five minutes recalling three specific positive memories with sensory details. This strengthens positive retrieval pathways and makes them more accessible during negative moods.

Recognize the bias in real-time. When you catch yourself thinking "nothing ever works out," that's a red flag that mood congruence is operating. The thought feels true because your current state is only showing you supporting evidence. Ask: "What am I not remembering right now?"

Exercise strategically. Physical activity improves mood, which shifts memory retrieval patterns. A 20-minute walk can provide enough mood lift to access a more balanced set of memories when making decisions or solving problems.

Curate your media consumption. When you're already down, deliberately choose media that contradicts your mood rather than confirming it. Sad music when sad feels cathartic but reinforces the cycle. Uplifting content creates cognitive dissonance that can interrupt automatic negative retrieval.

Build "mood-independent" relationships. Talk to people who know your full story, not just current struggles. They can remind you of strengths and successes your current mood is hiding from you.

Recent advances are pushing beyond description toward intervention. Researchers are exploring whether targeted brain stimulation or neurofeedback could temporarily modulate mood congruence effects, potentially "resetting" stuck patterns in treatment-resistant depression.

Artificial intelligence applications are emerging that analyze speech patterns and digital behavior to detect when someone is stuck in negative retrieval loops, triggering timely interventions. Imagine a phone app that notices you're doom-scrolling and suggests specific positive memory recall exercises calibrated to your history.

Understanding how positive affect amplifies memory integration is revealing opportunities for enhancing learning and skill development. Students might benefit from strategic mood management around study sessions, and professionals could optimize memory consolidation for important information.

The therapeutic implications keep expanding. Research on memory reconsolidation suggests that recalling emotional memories under controlled conditions might allow them to be "rewritten" with less emotional charge. This could revolutionize trauma treatment.

Investigations into early childhood memory formation are revealing that mood congruence patterns form young, suggesting early interventions could prevent problematic patterns from ever developing. Imagine teaching emotional regulation and balanced memory retrieval as foundational skills alongside reading and math.

The next generation of mental health interventions won't just treat symptoms - they'll retrain the fundamental mechanisms by which your brain constructs your experience of reality.

The mood congruence effect reveals something profound about human consciousness: we don't experience objective reality. We experience our mood's interpretation of reality, assembled from selectively retrieved memories and biased attention to current circumstances.

This isn't cause for despair - it's cause for agency. If your current experience is constructed from biased retrieval, you can learn to interrupt that construction process. You're not doomed to be trapped by your past. You're trapped by which parts of your past your current mood is choosing to show you.

For people struggling with depression and anxiety, understanding this mechanism provides both explanation and hope. The reason cognitive patterns feel so real and unchangeable is because mood congruence creates internally consistent narratives. Every memory your brain serves up confirms what you already feel. But consistency isn't truth - it's selective retrieval.

For everyone else, awareness of mood congruence provides a powerful tool for clearer thinking, better relationships, and wiser decisions. When you catch your mood coloring your memories, you can step back and ask: "What am I not seeing right now? What would I remember about this situation if I felt differently?"

Your memories aren't lying to you. But your mood is choosing which truths to tell and which to hide. Understanding that selection process is the first step toward seeing more completely - and choosing more wisely what to remember, what to learn from, and what to leave behind.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

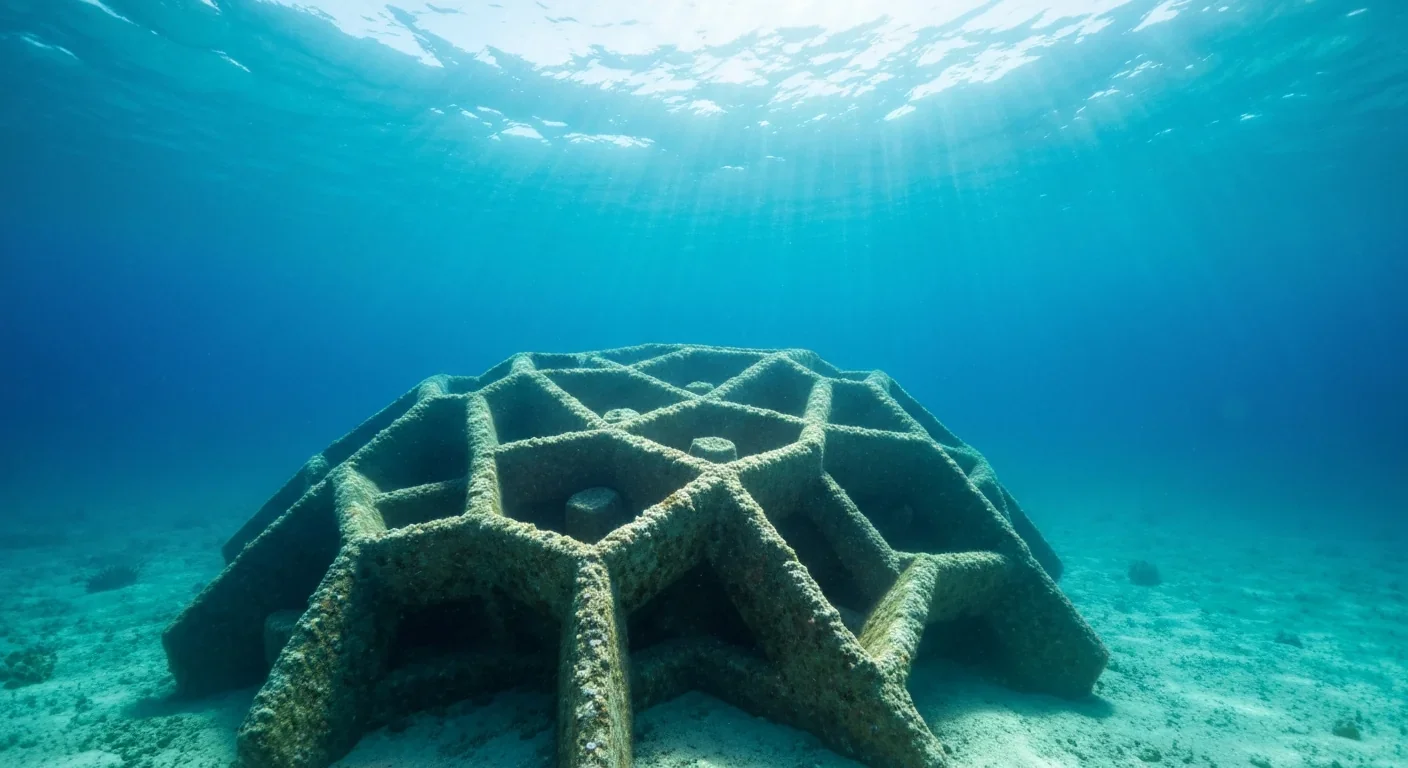

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

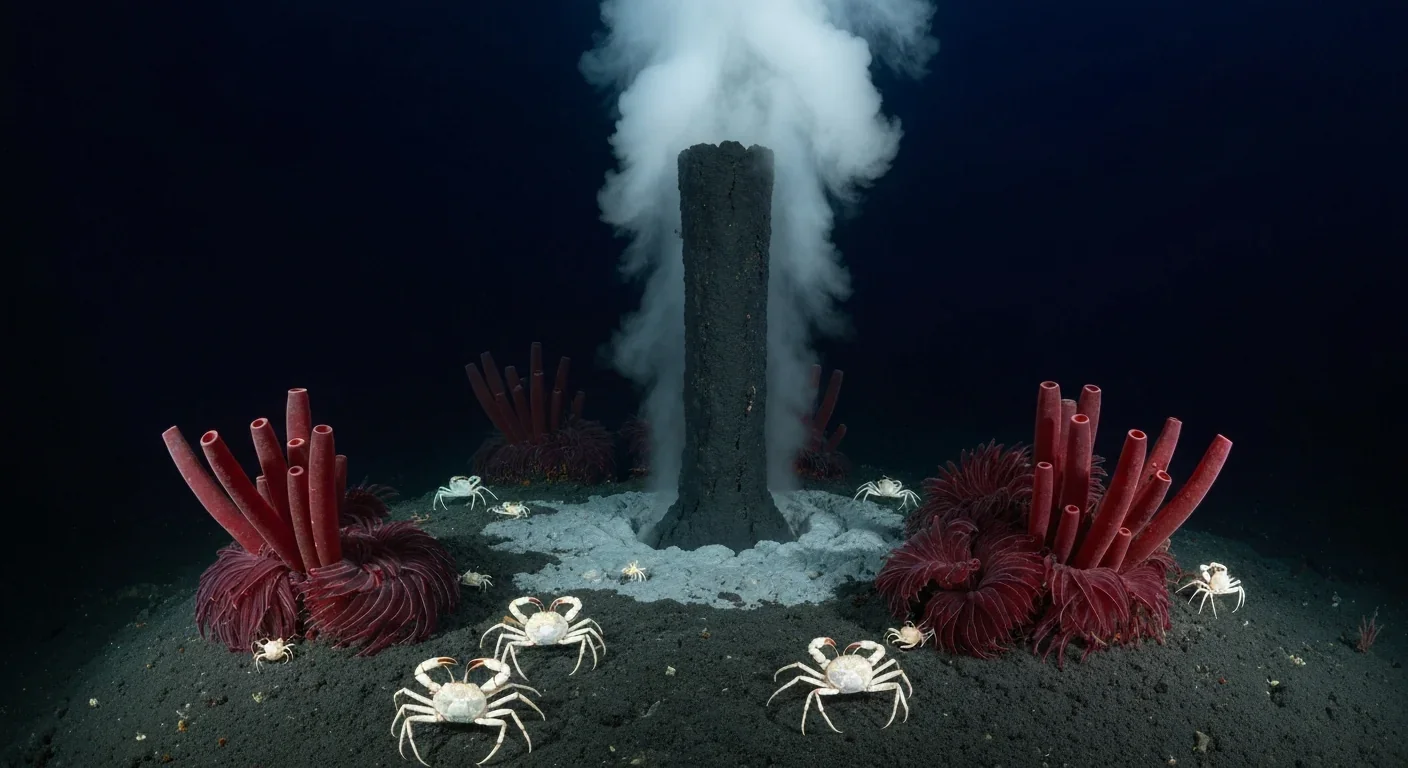

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

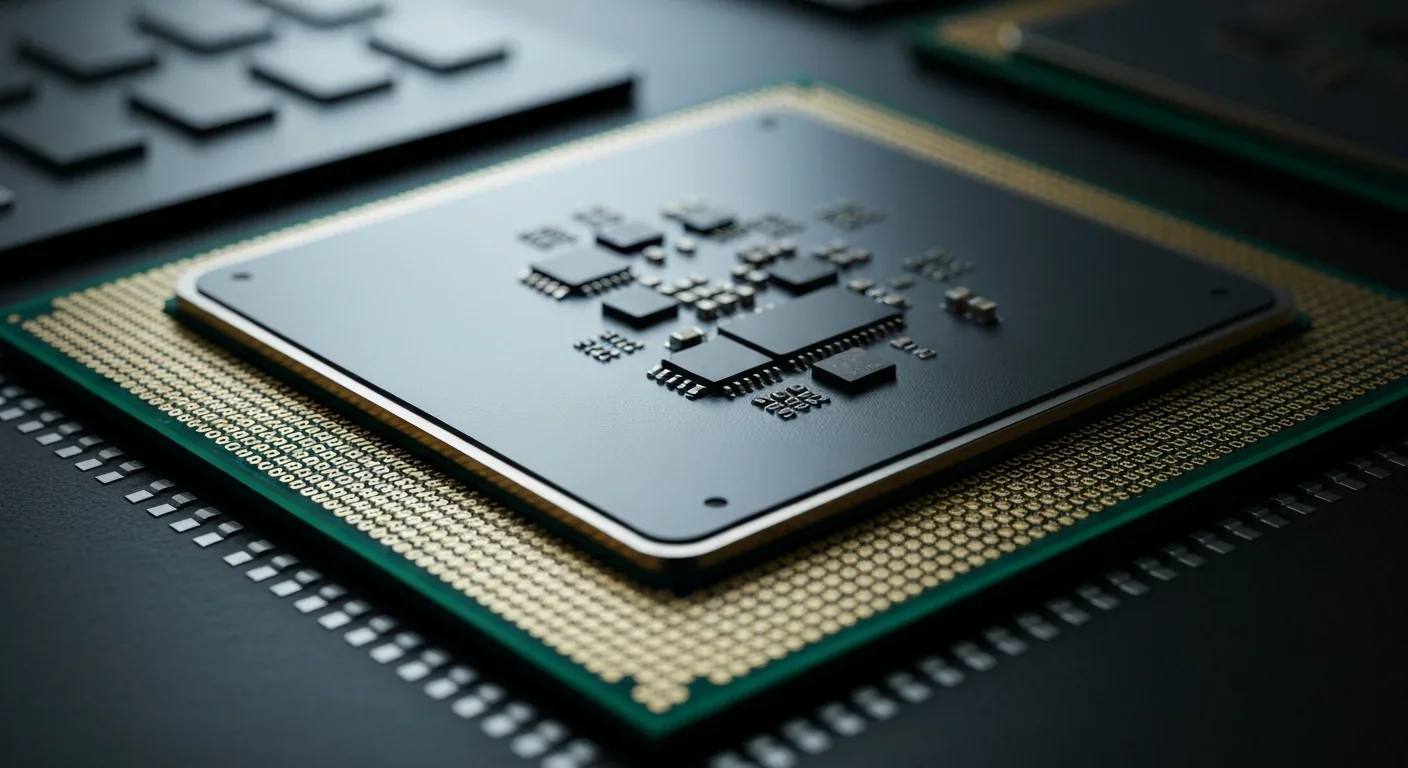

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.