The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: Your brain doesn't remember experiences as they happened - it judges them based on the most intense moment and the ending. Understanding this cognitive bias can help you design better experiences and make smarter decisions.

You remember the vacation where you got food poisoning on day three but watched an incredible sunset on the final evening. Years later, you'll call it "amazing." Your brain just lied to you, and a Nobel laureate can explain why.

Daniel Kahneman discovered something unsettling about human memory: we don't actually remember experiences the way they happened. Instead, our brains take a shortcut. They grab the most intense moment (the peak) and the final moment (the end), average them together, and toss out everything else. He called it the peak-end rule, and it's been messing with our decisions ever since.

In the early 1990s, Kahneman and his colleagues did something slightly cruel to prove their theory. They asked people to stick their hands in painfully cold water. Group A endured 60 seconds at 14°C (57°F), then pulled their hands out. Group B got the same 60 seconds, but then had to keep their hands submerged for an additional 30 seconds while the water warmed slightly to 15°C.

Logic says Group A had it better because they suffered less total pain. But when asked which experience they'd rather repeat, most people chose Group B. The slightly less awful ending convinced their brains the whole thing wasn't so bad, even though they'd objectively suffered more.

Your brain doesn't care how long something lasted. It cares about how it felt at its worst (or best) and how it ended. This is duration neglect in action.

That's duration neglect in action. Your brain doesn't care how long something lasted. It cares about how it felt at its worst (or best) and how it ended.

The colonoscopy study took this from lab curiosity to medical revelation. Kahneman and physician Donald Redelmeier tracked patients undergoing colonoscopies in 1996, measuring their real-time pain every 60 seconds.

Some procedures ended abruptly when the scope was removed. Others ended with the scope left in place, stationary, for an extra minute or two. This final period was still uncomfortable but less painful than the active examination.

When patients later recalled the experience, those who had the extended, less-painful ending remembered the entire procedure as less awful, even though they'd endured more total discomfort. The finding was so robust that some medical facilities changed their protocols to deliberately add a low-pain period at the end of uncomfortable procedures.

"Your experiencing self suffers through every moment. Your remembering self writes the story afterward and decides what goes in the official record. These aren't the same person, and the remembering self holds all the power."

- Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist

Why does your brain do this? Evolution didn't design your memory to be a video recorder. It designed memory to help you make predictions about the future based on past experiences.

If you're deciding whether to return to a restaurant, your brain doesn't need to recall every bite. It needs a quick judgment: good or bad? The peak-end rule provides that shortcut. The best dish (peak) and the quality of service as you left (end) give you enough data to make a fast decision.

Researchers have identified several factors that make the peak-end rule stronger or weaker. Novel experiences show a stronger peak-end effect than routine ones. Negative experiences tend to create sharper peaks than positive ones because your brain prioritizes threat detection. And the more emotionally intense an experience, the more your memory compresses it into those two critical moments.

The rule appears across cultures and age groups, though some research suggests individual differences in how strongly people weight peaks versus ends. Those with higher trait anxiety tend to give more weight to negative peaks, while optimistic personalities may emphasize positive endings.

Once companies understood the peak-end rule, they started weaponizing it. Disney doesn't place its gift shops randomly. They're strategically positioned at ride exits, so your last memory of Space Mountain is buying a souvenir while still buzzing from the drop.

Airlines know this too. Even if your flight featured turbulence, delays, and a crying baby, a smooth landing and efficient deplaning can salvage your memory of the experience. Some carriers train flight attendants to be especially warm and attentive during the final 15 minutes, knowing it will disproportionately shape passenger satisfaction scores.

Hotels obsess over checkout experiences. A genuinely friendly desk clerk, a complimentary bottle of water for the road, or a simple "we hope to see you again" can transform a mediocre stay into a positive memory. Research shows that guests who rate their checkout experience highly will give the entire hotel stay better reviews, even if they complained about room temperature or noise earlier.

The fitness industry has caught on too. Boutique gyms design classes to end with a feel-good cool-down featuring uplifting music and instructor encouragement. You'll forget the suffering in the middle when you're walking out energized and proud.

Not everyone uses this knowledge benevolently. Some companies deliberately create a frustrating experience, then "rescue" you at the end to seem heroic. Customer service departments that make you wait on hold for 40 minutes, then have a single empathetic agent solve your problem, are exploiting the peak-end rule.

The ethical questions get thornier in healthcare. If a doctor can make a procedure feel better by extending it slightly, should they always do so? What if the patient is paying by the minute? What if adding unnecessary time creates other risks?

Some critics argue that optimizing for remembered experience rather than lived experience is fundamentally manipulative. You're not actually improving someone's life, just hacking their memory of it.

Some critics argue that optimizing for remembered experience rather than lived experience is fundamentally manipulative. You're not actually improving someone's life, just hacking their memory of it. The counterargument: if the remembering self is what makes future decisions, improving that memory has real consequences for behavior and wellbeing.

Here's where it gets personal. The peak-end rule doesn't just affect your memory of vacations and medical procedures. It shapes how you remember the people in your life.

Psychologists have found that romantic relationships fall prey to this bias constantly. A partner might be consistently kind and supportive for months, but one explosive argument becomes the peak that defines your memory. Or worse: a relationship that's been deteriorating for years gets a brief positive moment near the end, and suddenly you're convinced you made a mistake breaking up.

Parents experience this acutely. You spend hours helping your kid with homework, playing games, and having good conversations. But if the day ends with a bedtime tantrum, that's the memory that sticks. Your retrospective judgment of "how today went with the kids" will weigh that final meltdown far more heavily than the pleasant preceding hours.

The peak-end rule also explains why grudges persist. If your last interaction with someone ended badly, that ending dominates your memory of the entire relationship. All the good times compress into background noise.

Understanding the peak-end rule gives you leverage. If you're planning an event, a vacation, or even just a dinner party, you can use this knowledge deliberately.

Create a genuine peak. Don't spread your resources evenly. Concentrate effort on creating one moment that stands out. For a wedding, that might be an unexpected performance. For a conference, an exceptional keynote speaker. For a date, a surprise that shows genuine thoughtfulness.

End strong, always. The final moments matter enormously, so don't let them happen by accident. Restaurants that send diners home with a small gift or unexpected complimentary dessert understand this. Party hosts who walk guests to the door and thank them personally create better memories than those who let people slip out while they're cleaning up.

Downward trends beat upward ones. This seems counterintuitive, but it's proven. If you're delivering news that contains both good and bad elements, lead with the bad and end with the good. Your audience will remember it more positively than if you did the reverse.

You can also use the peak-end rule to combat its own distortions. When you're evaluating an experience, especially one that will inform a major decision, deliberately override your instincts.

Keep a journal with regular entries, not just summaries. Your retrospective journal entry about a trip will focus on peaks and ends. But if you wrote something every day during the trip, you'll have data your remembering self can't ignore.

Make decisions during experiences, not after. If you're trying to figure out whether you like your job, rate your satisfaction weekly while you're still in the moment. Don't wait until you're deciding whether to quit, when your brain will compress months of work into a few memorable highlights and a recent frustration.

Ask specific questions instead of general ones. "How was your day?" will trigger peak-end recall. "What happened at lunch?" or "Tell me about your morning meeting" will surface a more accurate picture.

When evaluating relationships, create a list of specific interactions rather than relying on your overall feeling. If you're considering whether a friendship is worth maintaining, don't ask "Do I enjoy spending time with them?" Ask "What did we do the last five times we hung out, and how did I feel during each one?"

For all we know about the peak-end rule, significant questions remain unanswered. Researchers still debate whether the effect is equally strong for positive and negative experiences. Some studies suggest we're better at remembering negative peaks, while others find no difference.

The role of surprise isn't fully understood either. Does an unexpected positive moment create a stronger peak than an anticipated one? Consumer research suggests yes, but the mechanism isn't clear.

And we don't really know how the peak-end rule interacts with other memory biases. What happens when your peak-end memory conflicts with your social identity? If you remember an event positively, but everyone else remembers it negatively, does social proof override the peak-end effect?

There's also the question of multiple peaks. Most experiences don't have just one intense moment. What if there are three or four? Does your brain average them? Weight the most recent one? Pick the most extreme? The research here is surprisingly thin.

The deeper implication of Kahneman's work isn't just that memory is unreliable. It's that the unreliable memory version becomes your reality.

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman describes two selves: the experiencing self that lives your life moment to moment, and the remembering self that tells the story afterward. The experiencing self gets to live more moments, but the remembering self makes all the decisions.

"Which self deserves priority: the one living through every moment, or the one constructing meaning afterward? Kahneman points out we're usually choosing for the remembering self without realizing it."

- Philosophical implication from Thinking, Fast and Slow

This creates genuine philosophical puzzles. If you're deciding between two vacations, should you pick the one that will be more pleasant to experience, or the one you'll remember more fondly? What if they're different? Which self deserves priority?

Some philosophers argue the experiencing self has primacy because it's the only one that's actually conscious during the events. The remembering self is just looking at records. Others counter that the remembering self is the one that builds your identity and makes meaning from your life, so its perspective matters more.

Kahneman himself doesn't resolve this tension. He just points out that we're usually choosing for the remembering self without realizing it, and maybe we should think harder about whether that's what we want.

The peak-end rule isn't something you can turn off. Evolution built this shortcut deep into your cognitive architecture. But you can learn to work with it instead of being victimized by it.

When you're designing experiences for others, whether you're a parent planning a birthday party or a CEO crafting company culture, remember that people won't remember the average. They'll remember the peaks and the endings. Invest your energy accordingly.

When you're evaluating your own life, be suspicious of your first instinct. Your remembering self has an agenda, and it's not accuracy. Gather data, get specific, and make decisions based on the full picture rather than the highlight reel.

And when you're stuck in something difficult, remember that there's power in how you end it. The worst day of your life can still have a decent final chapter if you choose it deliberately. Your experiencing self will still suffer through the middle, but your remembering self - the one who has to carry this story forward - will have something to work with.

The peak-end rule reveals something both disturbing and liberating: your brain doesn't record reality. It tells stories. And once you know that, you can start choosing which stories to tell.

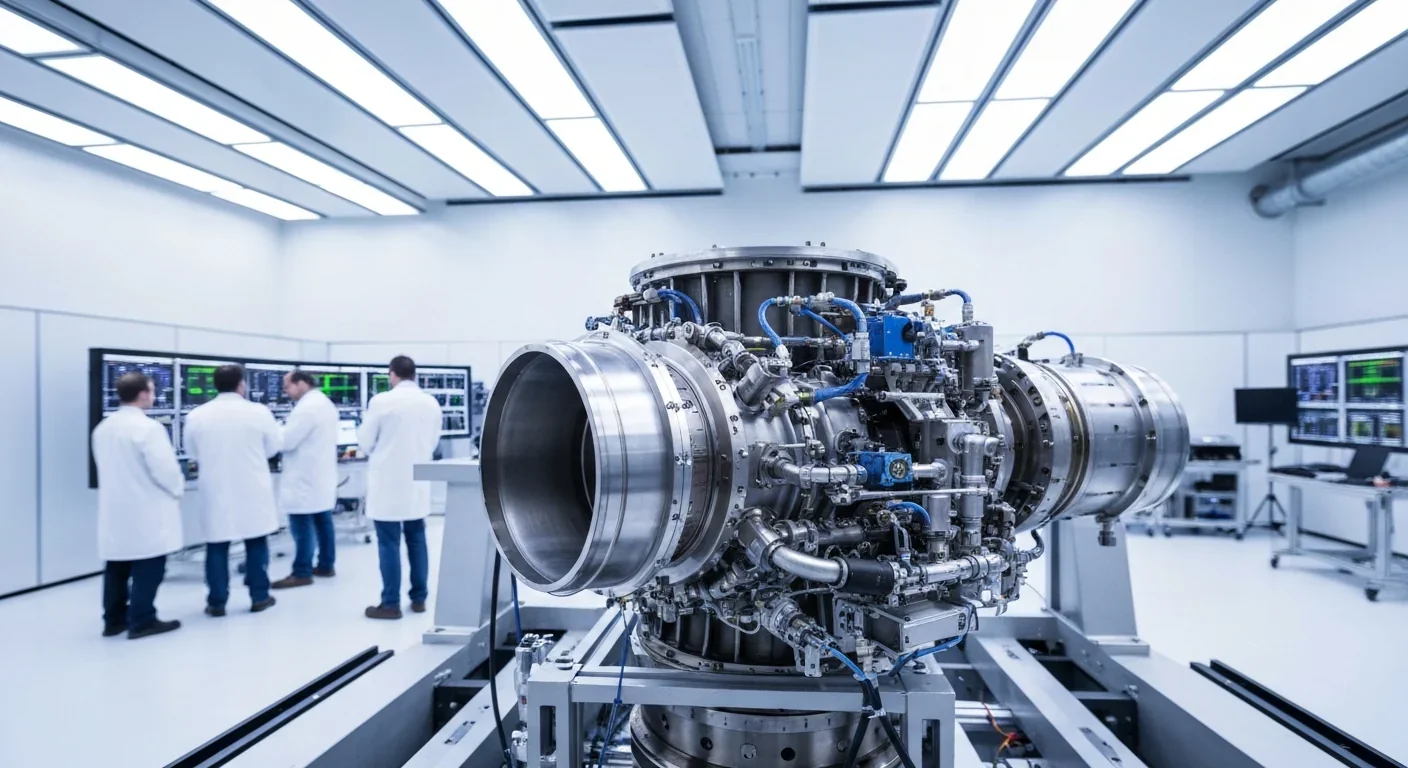

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

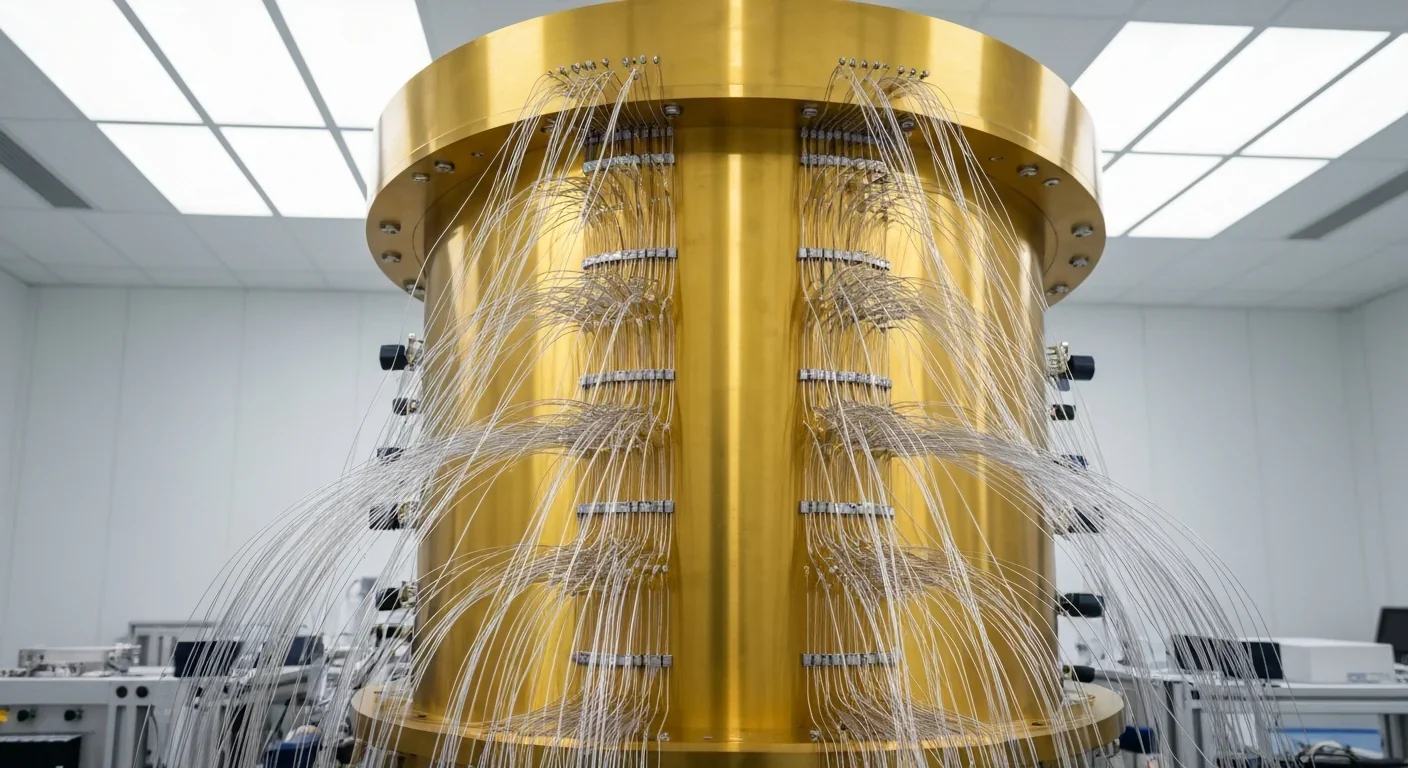

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.