The Pratfall Effect: Why Mistakes Make You More Likable

TL;DR: The sunk cost fallacy drives us to continue failing ventures simply because we've already invested resources. This cognitive bias, rooted in loss aversion and mental accounting, costs billions annually but can be overcome through structured decision-making frameworks that focus on future prospects rather than past investments.

You've already spent three years on a project that's clearly failing. Logic says cut your losses, but something deeper whispers: "Just a little more time, just a little more money, and it'll all pay off." That voice is the sunk cost fallacy, and it's quietly draining billions from our economy while reshaping everything from corporate strategy to personal relationships.

The sunk cost fallacy is deceptively simple: we continue investing in losing propositions simply because we've already invested so much. It's the reason governments funded the Concorde jet for 27 years after it proved unprofitable, burning through $2.8 billion. It's why you finish terrible books, stay in dead-end jobs, and hold onto plummeting stocks. But here's what makes this cognitive bias particularly dangerous in our interconnected world: as decision-making becomes more complex and stakes grow higher, our brains' ancient wiring increasingly works against us.

Recent research reveals this isn't just a human quirk. Studies show that rats, mice, and humans all demonstrate sensitivity to sunk costs after committing to pursue a reward. This cross-species pattern suggests the bias has deep evolutionary roots, making it far harder to overcome than simple awareness campaigns might suggest.

Understanding why we fall into this trap requires examining the mental machinery that drives our decisions. The sunk cost fallacy doesn't emerge from a single flaw but from an intricate web of cognitive biases and emotional responses that evolved to help us survive but now often lead us astray.

At the heart of the fallacy lies loss aversion, a principle discovered by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Research consistently shows that the pain of losing $100 feels roughly twice as intense as the pleasure of gaining $100. Dr. Yalda Safai, a psychiatrist who studies decision-making, explains: "The impact of loss feels worse than the prospect of gain, so we keep making decisions based on past costs instead of future costs and benefits."

The pain of losing $100 feels roughly twice as intense as the pleasure of gaining $100. This asymmetry drives us to throw good money after bad.

But loss aversion alone doesn't tell the whole story. Mental accounting, a concept pioneered by Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, reveals how we psychologically separate our resources into distinct categories or "accounts." When you buy a $150 concert ticket, that money enters a mental account labeled "concert experience." If a blizzard hits on concert night, you're more likely to risk dangerous driving because abandoning the ticket feels like closing that account at a loss.

Thaler demonstrated this through an elegant experiment. He and a friend received free tickets to a sporting event. When a snowstorm threatened, they decided not to risk the drive. But Thaler realized that had they purchased those tickets themselves, they would have felt compelled to go despite identical weather conditions and identical ticket value. The only difference? The psychological weight of having "invested" their own money.

Commitment bias adds another layer of complexity. Once we publicly commit to a course of action, backing away feels like admitting failure. Research by Hal Arkes and Catherine Blumer found that people systematically preferred opportunities with larger prior investments, even when smaller investments offered statistically better outcomes. In their classic ski-trip experiment, participants who had paid more for a vacation package reported feeling more obligated to enjoy it, even when weather or health issues made the trip unpleasant.

The desire to avoid appearing wasteful magnifies these effects. We're social creatures, and being seen as someone who "throws money away" carries real reputational costs. This social dimension helps explain why organizations often prove more susceptible to sunk cost fallacy than individuals: corporate decision-makers face intense pressure to justify past investments to boards, shareholders, and colleagues.

Studies reveal another surprising factor: the magnitude of loss directly correlates with bias intensity. The larger your investment, the harder it becomes to walk away, creating a vicious cycle where mounting losses paradoxically strengthen your commitment to failing ventures.

The most instructive examples of sunk cost fallacy occur not in laboratory experiments but in the high-stakes arenas of government policy and corporate strategy, where initial optimism collides with economic reality.

The Concorde supersonic jet gave this bias its alternative name: the Concorde fallacy. In the 1960s, Britain and France launched a joint venture to build the world's first supersonic passenger aircraft. Early projections suggested modest costs and strong market demand. Reality told a different story. By the early 1970s, cost overruns had spiraled out of control and market research showed limited commercial viability. But both governments had already invested hundreds of millions of pounds and faced enormous political pressure. Canceling would mean admitting a spectacular failure.

"People demonstrate a greater tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made."

- Behavioral Economics Research

So they doubled down. Then tripled down. The Concorde program continued for 27 years after its economic case collapsed, ultimately consuming roughly $2.8 billion. When commercial flights finally ended in 2003, only 20 aircraft had ever entered service. The Concorde was a technological marvel but an economic disaster - one that could have been prevented by recognizing sunk costs for what they were: unrecoverable and irrelevant to future decisions.

American nuclear power presents an equally sobering case study. Research by economists Werner De Bondt and Ashok Makhija examined U.S. nuclear utilities in the 1980s and found that companies delayed abandonment of nuclear plants for decades after massive cost overruns made projects economically untenable. Political commitments, regulatory approvals, and previous expenditures created psychological anchors that kept billions flowing into facilities that rational analysis would have shut down. The total wasted investment reached tens of billions of dollars.

Corporate America offers endless variations on this theme. Consider a manufacturing company that invests $5 million developing a new product line. Eighteen months in, market research reveals shifting consumer preferences that make the product obsolete. The rational decision is immediate termination, but executives who championed the project face career consequences. Meetings generate optimistic projections: "Just $2 million more and we can pivot the offering." Then another $2 million. The phenomenon repeats itself across industries: technology firms that refuse to kill failing software projects, pharmaceutical companies that continue funding drugs that failed Phase II trials, retailers that pour capital into underperforming store locations.

The personal toll may be harder to quantify but no less real. People remain in unfulfilling careers because they've already invested years earning specific credentials. They continue renovating houses that have become money pits. They hold romantic relationships together long past their expiration date because of shared history and investments.

One particularly deadly manifestation deserves special attention: plan continuation bias in aviation. NASA researchers analyzing 19 commercial aviation accidents discovered a chilling pattern. Pilots who had invested significant time and fuel following a specific approach plan continued that plan even when conditions made it clearly unsafe.

In several cases, pilots received multiple warnings about weather, mechanical issues, or navigational problems. The rational response would be aborting the approach and diverting to an alternate airport. But having already committed to landing at their planned destination, pilots persisted until catastrophe struck. The sunk cost wasn't money but time, fuel, and psychological commitment to a flight plan.

This same dynamic appears in maritime disasters, military operations, and medical emergencies. When individuals or teams have invested heavily in a course of action, admitting that circumstances demand a complete reversal becomes psychologically nearly impossible, even when lives hang in the balance.

If sunk cost fallacy affects individuals, it absolutely decimates organizations. Corporate structures create unique vulnerability factors that turn a cognitive bias into an existential threat.

Diffuse responsibility means that the people continuing a failing project often aren't the same ones who initiated it. A new project manager inherits a struggling initiative but feels pressure to honor previous leaders' commitments. Groupthink emerges as team members reinforce each other's rationalizations rather than acknowledging failure. Meeting rooms fill with optimistic reframings: "We're not failing, we're iterating." "This is a learning opportunity." "Quitters never win."

Corporate decision-makers face intense pressure to justify past investments. Saying "We wasted $50 million" feels like confession, while "We've invested $50 million" sounds like leadership.

Career incentives create particularly perverse dynamics. Executives know that championing bold initiatives can accelerate promotion, but admitting those initiatives failed carries severe penalties. The result? Leaders who double down on questionable projects to avoid career damage, gambling with company resources to protect their reputations.

Accountability structures paradoxically amplify the bias. Decision-makers feel they must justify past expenditures to boards, shareholders, and colleagues. Saying "We wasted $50 million, and we should stop now before wasting $100 million" is psychologically far harder than saying "We've invested $50 million, and $25 million more will turn this around." The first statement feels like confession; the second sounds like leadership.

Research by organizational psychologists reveals that team environments can reduce sunk cost bias when considering harm to others. When decisions primarily affect team members rather than the decision-maker personally, people show more willingness to cut losses. But this protective effect vanishes when the team itself has collective investment in the project's success.

Not all research on sunk cost fallacy delivers grim news. Recent studies identify factors that reduce susceptibility, offering hope that this deeply embedded bias isn't inevitable.

A 2021 study by David Ronayne and colleagues found that capacity for cognitive reflection significantly reduces sunk cost behavior. Cognitive reflection means the ability to override intuitive responses and engage analytical thinking. People who score high on cognitive reflection tests prove more likely to recognize sunk costs as irrelevant and make forward-looking decisions.

This matters because cognitive reflection can be developed. Unlike intelligence or personality traits that remain relatively fixed, the metacognitive skill of questioning your initial reactions improves with practice and awareness.

Another promising finding: considering the welfare of others serves as a natural check on sunk cost bias. When your decision primarily affects other people, you're more likely to abandon failing ventures. This suggests that reframing business decisions to emphasize stakeholder impact rather than vindicating past investments might reduce organizational vulnerability.

Recognizing the sunk cost fallacy represents a crucial first step, but knowledge alone doesn't prevent the bias. Research and professional experience reveal that effective mitigation requires structured approaches that counteract our psychological vulnerabilities.

The counterfactual question cuts through emotional attachment: "If I hadn't already invested anything, would I commit these resources now?" This mental reset strips away the psychological weight of prior investment. Investment professionals routinely use this technique when evaluating whether to hold or sell positions. The question forces evaluation based solely on future prospects rather than past decisions.

"Sunk costs are expenses, whether time, money, or effort that can't be recovered, yet they often influence future decisions - much to the detriment of the individual or business."

- Investopedia

Pre-commitment to decision rules prevents emotional escalation. Before starting any significant project or investment, establish clear criteria that will trigger termination. For financial investments, this might mean stop-loss orders - automated instructions to sell when assets drop below a predetermined price. For projects, it might mean milestone reviews where continuation requires meeting specific metrics. The key is establishing these rules before emotional investment clouds judgment.

Regular milestone reviews create natural checkpoints for reassessment. Rather than treating projects as continuous commitments, break them into phases with mandatory evaluation between stages. Project management platforms like Asana now automate these checkpoints, sending reminders to assess whether continuation serves future goals rather than vindicating past spending.

External perspective neutralizes personal attachment. People evaluate others' situations more objectively than their own. When struggling with a potential sunk cost situation, describe the scenario to a trusted colleague or mentor without revealing it's your situation. Their advice will likely prove more rational than your internal reasoning. For major business decisions, engaging external consultants or advisory boards provides perspectives unclouded by organizational history.

Decision matrices formalize evaluation criteria. Rather than relying on intuition or defending past investments, systematically score options across predetermined factors like projected return on investment, strategic alignment, resource requirements, and market conditions. This structured approach makes it harder for sunk cost bias to hijack the decision process. The scoring must be honest, which is why having uninvolved parties participate in the evaluation adds value.

The counterfactual question: "If I hadn't already invested anything, would I commit these resources now?" This mental reset strips away the psychological weight of prior investment.

Reframing the narrative transforms how you conceptualize the decision. Instead of "We've already spent $2 million, so we can't quit now," try "We've gathered $2 million worth of information that tells us this direction won't work. What's the best path forward given what we now know?" This linguistic shift repositions past investments as learning rather than waste, reducing the psychological pain of abandonment.

Separating past from future in accounting and reporting practices helps organizations maintain clarity. Some companies now track "sunk costs" and "going-forward costs" in separate columns on project reports, making it visually obvious which numbers matter for future decisions. This simple format change can significantly improve decision quality by fighting our mental accounting tendencies.

Sunk cost fallacy doesn't exist in a vacuum. Cultural values around persistence, commitment, and loyalty shape how we experience and respond to this bias.

Western culture, particularly in the United States, valorizes persistence. "Winners never quit, and quitters never win." "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." These aphorisms embed themselves in our identity from childhood. Admitting a course of action was misguided feels not just like poor judgment but like a moral failure, a character flaw.

Eastern cultures often add layers of social obligation that intensify commitment. Saving face, honoring commitments to collaborators, and maintaining group harmony can make abandoning failing ventures even more psychologically costly. Research in organizational behavior suggests these cultural factors may help explain why some multinational corporations show different sunk cost patterns in different regional offices despite identical corporate policies.

The startup world provides a fascinating case study in cultural attitudes toward sunk costs. Silicon Valley culture increasingly embraces "failing fast" as a virtue. The term "pivot" - originally meaning a basketball move - now describes the ability to abandon an initial business model when evidence demands it. Companies celebrate pivot stories: Instagram started as a location-based check-in app called Burbn before abandoning most features to focus exclusively on photo sharing.

Yet even in this supposedly failure-tolerant culture, sunk cost bias thrives. Venture capital firms report that founders frequently resist pivoting because they've become emotionally attached to their original vision. The difference is that investors, sitting one step removed from the emotional investment, can more objectively identify when pivots are necessary.

The sunk cost fallacy isn't going away. Millions of years of evolution wired these cognitive patterns deep into our brains, and no amount of education will eliminate them entirely. But we can build decision-making systems that account for and counteract our biases.

For individuals, this means developing metacognitive awareness - the ability to recognize when you're rationalizing rather than reasoning. It means building accountability partnerships where trusted colleagues can challenge your thinking. It means pre-committing to decision rules before emotions escalate.

For organizations, it requires even more systematic approaches. Regular project portfolio reviews where every initiative must rejustify its existence create natural exit ramps. Separating project champions from project evaluators prevents personal incentives from distorting assessment. Rewarding leaders for shutting down failing initiatives, not just launching successful ones, realigns career incentives with rational decision-making.

Technology increasingly offers tools to help. Project management software can automate milestone reviews and flag when projects exceed predetermined thresholds. Decision support systems can present options in formats that minimize framing effects and highlight forward-looking criteria. Artificial intelligence might eventually identify patterns of escalating commitment before they become crises.

The deeper challenge is cultural. We need to reconceptualize terminating failing projects not as admission of defeat but as evidence of learning and adaptation. Organizations that celebrate "intelligent failures" - ventures that were reasonable risks but didn't pan out - create environments where people feel psychologically safe cutting losses.

Perhaps the most profound insight from sunk cost research is this: our brains fundamentally misunderstand waste. We think abandoning a failed investment means "wasting" what we've already spent. But sunk costs are already spent whether we continue or quit. The money, time, and effort are gone. They're not coming back.

The real waste occurs when we throw additional resources into ventures that rational analysis tells us won't succeed. Every dollar spent continuing a doomed project is a dollar unavailable for opportunities that might actually pay off. Every hour spent finishing a terrible book is an hour you could have spent reading something wonderful. Every year spent in the wrong career is a year you could have spent building a fulfilling alternative.

Economic theory has known this for decades. The "Bygones Principle" states clearly: only future consequences matter for rational decision-making. Past investments are, quite literally, history. They provide information about how we got here but shouldn't determine where we go next.

Our psychology, though, never got the memo. Evolution optimized our brains for small-scale social environments where reputation and consistency carried enormous survival value. In that world, being known as someone who follows through on commitments, even difficult ones, offered real advantages. The modern economy demands flexibility and evidence-based adaptation - qualities that conflict with ancient psychological imperatives.

Understanding sunk costs properly requires grasping their shadow: opportunity costs. Every resource devoted to one purpose becomes unavailable for alternatives. When you continue funding a failing project, you're not just losing the money you continue to invest. You're losing every potential alternative use of those resources.

Business strategists increasingly frame decisions through this lens. Major consulting firms now train clients to think not about what they've already spent but about the best alternative use of resources going forward. This mental shift can be transformative.

Imagine a company with a struggling product line that's consumed $10 million over three years. Management debates investing another $5 million for one more year. The sunk cost fallacy says: "We've invested $10 million; we can't quit now." The opportunity cost frame asks: "What's the best possible use of $5 million right now?" Maybe it's this product line. But maybe it's developing a different product, expanding successful existing products, acquiring a competitor, or returning capital to shareholders.

When framed as a competition between alternative futures rather than a referendum on past decisions, the choice often becomes clear. The past stops holding the future hostage.

As we move deeper into an era defined by rapid change, increasing complexity, and genuine uncertainty, the ability to recognize and overcome sunk cost bias becomes ever more critical. Industries that dominated for decades now face disruption in months. Technologies that seemed permanent become obsolete overnight. Career paths that felt secure vanish in waves of automation.

In this environment, the capacity to reassess commitments, abandon failing courses, and reallocate resources toward emerging opportunities separates thriving individuals and organizations from those that cling to the past until it drags them under.

The good news is that awareness is spreading. Behavioral economics has moved from academic theory to mainstream business practice. Concepts like sunk cost fallacy, loss aversion, and cognitive bias appear regularly in boardrooms, classrooms, and dinner table conversations. Each generation seems slightly better equipped to recognize these mental traps.

But awareness alone remains insufficient. We need systematic approaches that embed bias-resistant decision-making into our organizations, relationships, and personal habits. We need cultures that celebrate adaptability over stubborn persistence. We need to teach our children not just to work hard and honor commitments but also to recognize when changing course serves wisdom rather than weakness.

The sunk cost fallacy will likely always be with us, lurking in the shadows of every significant decision. But it doesn't have to control us. With understanding, structure, and deliberate practice, we can learn to see our past investments for what they are - information, not obligation - and make choices based on where we're going rather than where we've been.

The smartest decision isn't always persevering. Sometimes it's knowing when to walk away.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

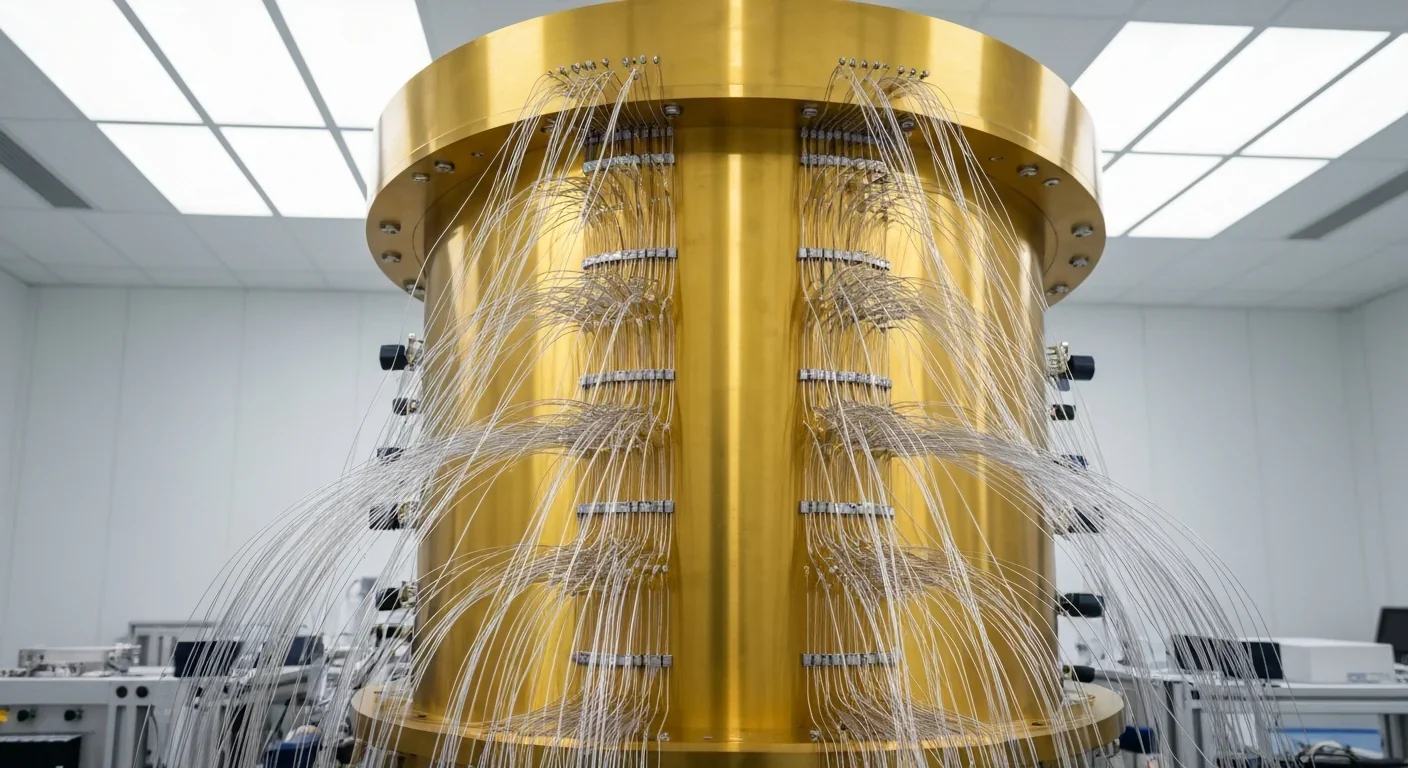

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.