Why We Pick Sides Over Nothing: Instant Tribalism Science

TL;DR: Cramming creates an illusion of learning through fluency, but spaced repetition works better because effortful retrieval strengthens memory. Scientific evidence from neuroscience to corporate training shows distributing learning over time produces vastly superior retention than massed practice.

You've been there. It's 2 AM, the exam's in six hours, and you're mainlining coffee while frantically highlighting textbook pages you should have read weeks ago. The information seems to stick as you review it over and over, creating a false confidence that evaporates the moment you sit down with the test paper. Cognitive psychology research has a name for what you're experiencing: the spacing effect, a phenomenon that explains why your all-nighter study sessions betray you when it matters most.

Here's the uncomfortable truth that educators have known for over a century: cramming is worse than ineffective. It's actively counterproductive for long-term learning. Yet students consistently choose it, seduced by the illusion of progress that massed practice creates. The alternative - spaced repetition - feels slower and less productive in the moment, which is precisely why it works so much better.

In the 1880s, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus did something remarkable: he spent years memorizing lists of nonsense syllables and meticulously tracking how quickly he forgot them. His self-experimentation revealed fundamental truths about how human memory actually works, truths that remain the foundation of modern learning science.

Ebbinghaus discovered what's now called the forgetting curve, showing that we lose 50-80% of newly learned information within days without reinforcement. But he also found something more intriguing: information reviewed at spaced intervals required dramatically less time to relearn than information studied in concentrated blocks. He called this phenomenon "savings," though today we know it as the spacing effect.

What made his work so valuable was its deliberate simplicity. By using meaningless syllables rather than meaningful content, Ebbinghaus isolated pure memory processes from the confounding effects of prior knowledge. Contemporary research has now confirmed the spacing effect works just as powerfully with complex, meaningful material in real-world settings.

The replication has been extraordinary. Hundreds of studies across different age groups, from young children to older adults, have confirmed Ebbinghaus's original findings. The spacing effect isn't a quirk of memory or an artifact of laboratory conditions. It's how human memory fundamentally operates.

Ebbinghaus discovered that we lose 50-80% of newly learned information within days without reinforcement - but information reviewed at spaced intervals requires dramatically less time to relearn than information studied in concentrated blocks.

There's a cruel irony at the heart of cramming: it produces exactly the feedback that makes you think it's working. When you review material repeatedly in a single session, each repetition feels easier and more fluent. You recognize the information quickly and experience what psychologists call "fluency illusions." Your brain interprets this ease as evidence of learning.

But fluency and actual learning are different things. What feels like mastery during concentrated study is often just short-term familiarity. The information hasn't been encoded into long-term memory in a durable way - it's simply hovering in working memory, where it will dissipate within hours or days.

Research shows students consistently underestimate the benefits of spacing and overestimate the benefits of massed practice. This metacognitive failure isn't stupidity or laziness. It's a predictable consequence of how we perceive our own learning. The ease of cramming feels productive, while the difficulty of retrieving spaced information feels like failure, even though that difficulty is precisely what strengthens memory.

The problem compounds when exam schedules reward cramming. If your test is tomorrow and you haven't studied, spacing your practice over several days isn't an option. You cram because you have to, and if you pass the exam, the strategy seems validated. But studies demonstrate that students who crammed often can't recall the material days afterward, even when they performed well initially.

There's also a less discussed problem with cramming: cognitive overload. When you try to absorb large amounts of information in compressed time, your working memory becomes saturated. For students with ADHD or learning differences, this overload is even more pronounced, making cramming particularly ineffective.

Understanding why spaced repetition works requires looking at what happens in your brain between study sessions. When you first learn something, it creates a fragile memory trace - a pattern of neural connections. These initial connections are weak and easily disrupted by interference or time passing.

Here's where the magic of spacing comes in. When you try to retrieve information after a delay, your brain has to work harder to access those memory traces. This effortful retrieval isn't a bug; it's the mechanism that strengthens the connections. Each successful retrieval makes the memory more resistant to forgetting, a process neuroscientists call "retrieval-induced learning" or the testing effect.

"The difficulty of retrieval matters. Items that are slightly difficult to recall produce stronger learning than items that are either too easy or impossibly hard. The intervals are set so you're on the edge of forgetting, which is precisely where retrieval practice is most effective."

- Cognitive Psychology Research

Neuroimaging studies show that spaced learning produces different patterns of brain activation than massed learning. Spaced repetition engages regions associated with effortful retrieval and memory consolidation, while massed practice shows more activation in areas associated with simple recognition and familiarity. Your brain is literally processing the information differently depending on how you space your study.

Between study sessions, your brain does crucial work during sleep and rest periods. Memory consolidation - the process of transferring information from temporary storage to long-term memory - happens largely offline. When you space your learning, you give your brain multiple consolidation opportunities, each one strengthening the memory trace. Cramming doesn't provide these crucial rest periods.

Spaced repetition also promotes what's called "elaborative encoding." When you return to material after a delay, you're more likely to think about it in new contexts, make connections to other knowledge, and process it more deeply. Research indicates this deeper processing is one reason spaced learning is particularly effective for complex, conceptual material.

Even animal studies confirm this. Experiments with fruit flies showed that flies exposed to a shocked odor on spaced occasions avoid that odor for a week or longer, while flies given massed exposure only avoid it for hours. Even at the most basic level of neural function, spacing creates more durable memories than massing.

Not all spacing schedules are equal. The general principle: optimal spacing intervals increase as the desired retention period increases. If you need to remember something for a week, you should space your reviews differently than if you need to remember it for years.

For most learning goals, research suggests a good rule of thumb: the first review within 24 hours of initial learning, the second after a few days, the third after a week or two, and subsequent reviews at increasing intervals. This creates what's called an "expanding schedule," which studies have found particularly effective for complex material.

But there's nuance here. Some research indicates that "uniform spacing" - keeping intervals constant - works better for certain types of learning, particularly factual information. Other studies have found that the relationship between spacing intervals and retention follows what's called a "temporal ridgeline," where there's an optimal interval length depending on when you need to retrieve the information.

Modern spaced repetition software uses algorithms that automatically adjust intervals based on your performance. The most common approach, used by programs like Anki, increases intervals for items you recall successfully and shortens them for items you struggle with.

One particularly interesting finding: the difficulty of retrieval matters. Items that are slightly difficult to recall - where you have to think for a moment before the answer comes - produce stronger learning than items that are either too easy or impossibly hard. This "desirable difficulty" principle explains why optimal spacing creates a bit of struggle. The intervals are set so you're on the edge of forgetting, which is precisely where retrieval practice is most effective.

Understanding the science is one thing. Actually implementing spaced repetition is another. The good news: you don't need sophisticated software or complex systems to benefit from spacing. The bad news: it requires planning ahead and resisting the temptation to cram.

The simplest approach is the "flashcard method." Create flashcards for information you need to learn, then review them on an expanding schedule. Start with daily reviews, then every other day, then twice a week, then weekly. Physical flashcards work fine, but digital systems like Anki or Quizlet automatically track when each card should be reviewed.

For more complex learning, the principle remains the same. When learning a new skill, space your practice sessions rather than doing marathon sessions. Musicians have known this for years: practicing an instrument for 30 minutes daily produces better results than practicing for 3.5 hours once a week, even though the total time is the same.

A study of 600 frontline workers found that 69% recalled at least half their training content after 30 days, and 54% still retained that much after six months - dramatically better than typical retention rates. The difference? Training was delivered in spaced intervals rather than intensive workshops.

Corporate training provides compelling real-world evidence. A study of 600 frontline workers found that 69% recalled at least half their training content after 30 days, and 54% still retained that much after six months - dramatically better than typical retention rates. The difference? Training was delivered in spaced intervals rather than intensive workshops.

Another study examined 64 sales associates learning new product information. Half received traditional training: a concentrated six-day session. The other half received the same content spread across six one-day sessions with week-long breaks. The spaced group didn't just perform better on tests - they reported higher confidence and better customer engagement months later.

Medical education provides perhaps the most dramatic demonstration. When medical students learned about vitamin D through spaced repetition rather than traditional massed study, their test scores were significantly higher 24 weeks later. This isn't trivial memorization - it's complex medical information that doctors need to retain for years.

For students, the key is building spacing into your semester from the beginning. When you learn new material in class, review it that evening. Review it again a few days later, then a week later, then before the exam. This approach requires less total study time than cramming while producing vastly better retention.

Teachers can implement spacing by deliberately revisiting topics throughout a curriculum rather than treating each topic as a discrete unit that's "finished" once you move to the next chapter. Studies show that distributing mathematical practice across three days leads to better performance up to six weeks later compared to massing the same practice in a single day.

Spaced repetition isn't a magic bullet, and it works even better when combined with other evidence-based learning strategies. The most powerful combination is spacing plus active retrieval - not just reviewing information, but actively trying to recall it without looking.

Retrieval practice amplifies the spacing effect because it adds another mechanism that strengthens memory: the act of retrieval itself. When you force yourself to recall information rather than simply re-reading it, you're creating stronger retrieval pathways. Combine this with spaced intervals, and you get a multiplicative benefit.

Interleaving - mixing different types of problems or topics within a study session - also works synergistically with spacing. Instead of doing 20 algebra problems followed by 20 geometry problems, interleaving means mixing them together. This approach feels more difficult and initially produces more errors, but it leads to better long-term learning.

Another powerful combination is spacing plus elaboration. When you review material at spaced intervals, actively work to connect it to what you already know, generate examples, or explain it in your own words. This deep processing creates richer memories that are more resistant to forgetting and easier to apply in new contexts.

For motor skills, spacing works well with "variability of practice." Instead of repeatedly practicing the exact same movement, introduce slight variations. A basketball player practicing free throws might vary their position slightly, or a musician might practice a passage in different keys. Combined with spacing, this variability produces more flexible, robust skills.

The key insight is that effective learning isn't about any single technique - it's about combining evidence-based approaches. Spacing provides the temporal structure that allows memory consolidation. Retrieval practice strengthens recall pathways. Elaboration creates meaningful connections. Together, they create learning that sticks.

Some researchers are now asking: what if we designed educational systems around spacing from the ground up, rather than treating it as an optional study technique? The implications would be radical.

Imagine a curriculum where topics aren't taught once and tested once, but instead revisited at carefully designed intervals throughout the year. Students might learn about photosynthesis in biology, then encounter it again weeks later when discussing carbon cycles in earth science, then return to it months later when learning about biofuels in chemistry.

"By slowing down - by distributing learning over time rather than compressing it - we actually learn faster and better. We retain more while studying less. We understand deeper while feeling less overwhelmed."

- Learning Science Research

Some innovative schools are already experimenting with this approach, using what's called "spiral curricula" where core concepts are revisited repeatedly throughout students' education. Early results are promising, showing better long-term retention without requiring more total instructional time.

Technology makes this more feasible than ever before. Adaptive learning platforms can track exactly when each student last encountered each concept and automatically schedule reviews at optimal intervals. Within the next decade, we'll likely see these systems become standard in both schools and corporate training.

This could reshape how we think about expertise. Currently, we often define expertise by what you can do after intensive study. A spacing perspective would emphasize what you can still do months or years later, with minimal review. That's a more meaningful definition of genuine learning.

Corporate training is already moving in this direction. Companies are discovering that spaced microlearning - short training modules delivered at spaced intervals - produces 250% better long-term retention than traditional intensive workshops, while requiring less total time away from work.

The spacing effect isn't just an academic curiosity. It's a fundamental principle of how human memory works, validated across thousands of studies. If you take away one insight, it should be this: the feeling of productive learning can be completely divorced from actual learning.

Cramming feels effective because it produces fluency and familiarity. But fluency isn't the same as durable learning. Spaced repetition feels harder and less productive because retrieval from memory requires effort. But that effort is precisely what creates learning that lasts.

For students, this means starting earlier and spreading study sessions across days and weeks rather than compressing them into marathon sessions. For educators, it means designing curricula that revisit important concepts at planned intervals. For professionals pursuing continuing education, it means building regular review into your schedule.

The practical implications extend beyond formal education. Learning languages, musical instruments, technical skills, or any domain requiring long-term retention will benefit from spacing. The techniques are the same: break learning into manageable chunks, review at increasing intervals, and embrace the productive difficulty that comes with effortful retrieval.

Perhaps most importantly, the spacing effect reveals something profound about human cognition: we're not designed for information binges. Our brains evolved to learn gradually, integrating new information with existing knowledge over time. When we try to force rapid learning through cramming, we're working against our cognitive architecture.

The irony is that by slowing down - by distributing learning over time rather than compressing it - we actually learn faster and better. We retain more while studying less. We understand deeper while feeling less overwhelmed. The approach that feels less productive is actually far more effective.

The science has been clear for over a century. The question now is whether we're ready to build our educational systems, our study habits, and our approach to lifelong learning around what actually works, even when it doesn't feel as satisfying as cramming. The answer will shape how the next generation learns, remembers, and builds expertise.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

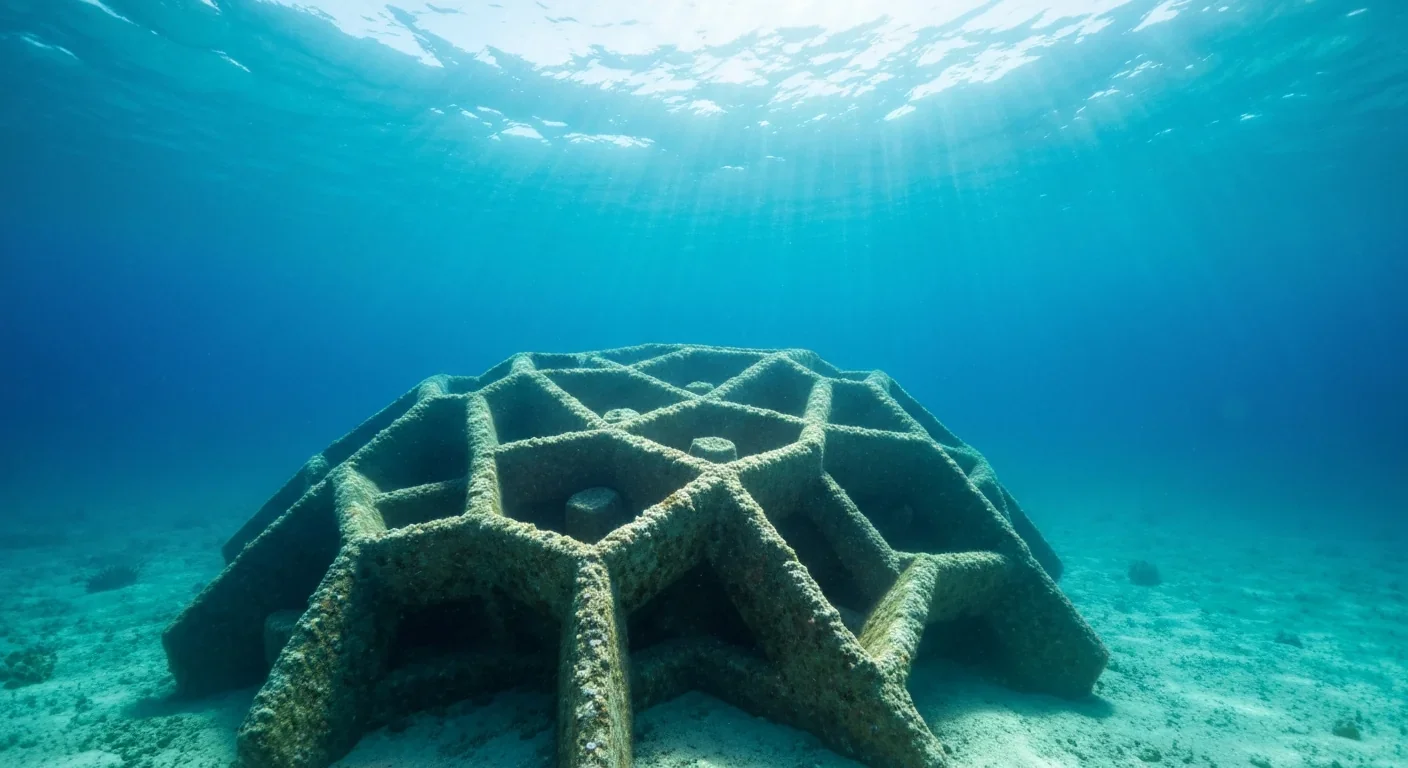

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

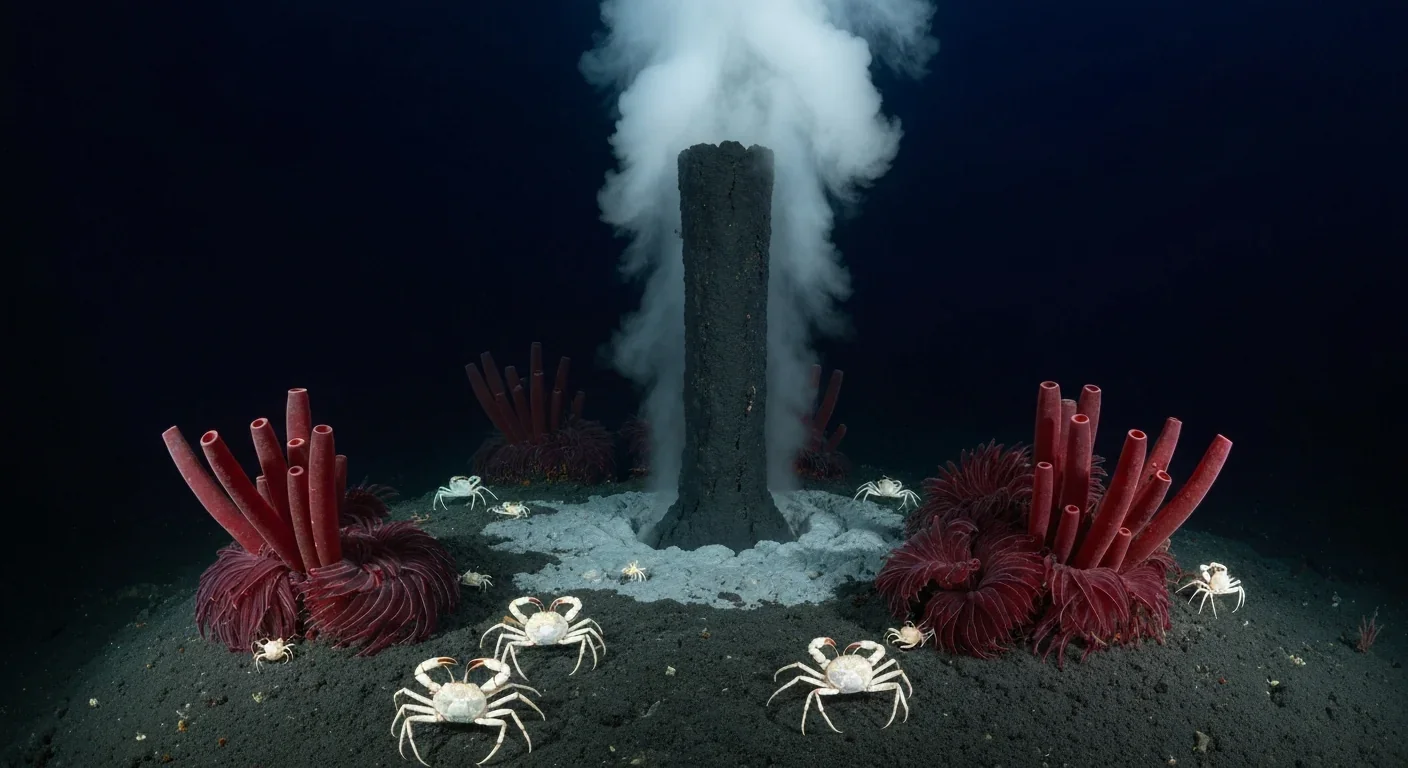

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.